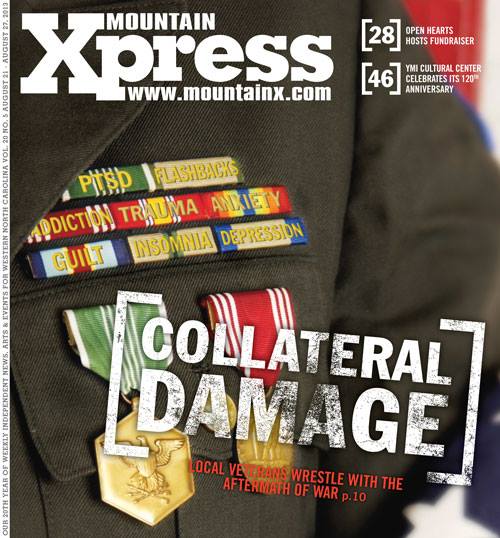

Iraq War veteran Kevin Plemmons regularly visits the local VA for counseling. Like many veterans, it took him years to get help. (Photos by Max Cooper)

“When the happy gods bring on the hard times,

bear them he must, against his will, and steel his heart.

Our lives, our mood and mind as we pass across the earth,

turn as the days turn.”

— Homer, The Odyssey

The framed photos stand at attention on a shelf in the living room. A drill sergeant in his broad-brimmed hat, and Marines and soldiers in their dress uniforms, stare straight ahead with fixed, unflinching gaze. Their eyes reveal no more about the unintended consequences of war and military life than what a collection of painted toy soldiers can teach a child about combat and casualties.

So when young Kevin Plemmons looked up at the gallery of his family’s military men, all he saw were heroes in big hats. Kevin’s Uncle Robert served in the Army for 20 years; cousins Craig and Chris proudly called themselves Marines. Two other cousins, Greg and Heath, enlisted in the Army.

To the young man growing up in Waynesville,N.C., these relatives represented an elite association of men who stood for valor, selfless service and an undying allegiance to God and country.

“I want to do that,” Plemmons remembers thinking. “They always talked about how good it was to serve.”

But they never mentioned things like night terrors or chronic pain. Guilt, depression, isolation and fear. And they absolutely never spoke about mental health.

• • •

On the plane back to the States, Ron Lapointe took a few sips of the booze being passed from soldier to soldier. Some men sat quietly, declining to take a swig. Others guzzled gladly at the end of their stint in Vietnam.

Lapointe had landed in the country’s central highlands a little more than a year before. On the first day of his deployment in August 1967, the former UCLA international relations student found himself wrapped in a poncho, knee-deep in mud, awaiting orders.

“Do you need any 11 Charlies?” (military speak for an infantry mortarman, Lapointe’s occupational specialty), one unknown man barked to another. “Do you need any 11 Charlies out there?” he repeated.

But at that moment, louder than even the yelling man and biting rain, Lapointe’s intuition told him, “You’re going to be OK.” Somehow, he remembers, he knew he would survive. And now here he was, heading home.

David Paul O’Brien had famously burned his draft card on the steps of the South Boston Courthouse a year before Lapointe landed in the Vietnamese jungle. But by the time Lapointe’s boots once again touched American soil two years later, the anti-war movement had grown. When he got off the plane, protesters were waving signs with the words “baby killer” smeared across them.

“In World War II, you got a parade and community support,” says Lapointe. “But for Vietnam vets, you got community rejection.”

His family, however, embraced him. And after throwing himself into completing his undergraduate studies and attempting to return to his former life, Lapointe flew from Los Angeles to New York to visit his sister, who’d recently moved there.

As he ran through Times Square to catch the next train leaving Grand Central Station for Long Island, a bus backfired. Instinctively, Lapointe dropped, his knees hitting the pavement as his arms came up to cover his head.

“That’s when I realized there were issues,” he says with a sigh.

Because on that plane ride back to America, he remembers, “The guys who had not been in combat were getting stupid drunk ― drinking and hollering and having a good old time. The guys who had been in combat were very quiet.”

Forty-four years later, Lapointe would finally be ready to break his silence.

• • •

Despite having no military base nearby, nearly 20,000 veterans call Buncombe County home ― giving it the sixth-biggest veteran population among the state’s 100 counties. In the five years that psychologist Elizabeth Huddleston has worked at Asheville’s Charles George VA Medical Center, the number of local veterans accessing mental health services has continued to rise, and she doesn’t expect that to change any time soon.

She reads aloud from a document on her desk: “From Oct. 1, 2006, to Oct. 1, 2011, the number of veterans accessing mental health service at Charles George VA Medical Center increased by more than 50 percent.” During that same period, the total number of people receiving specialized mental health care from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs increased annually, from 927,052 to more than 1.3 million in the last fiscal year.

And for this year, she continues, the local office is “already on track to show an increase in veterans seen for mental health services.”

But another trend, notes Huddleston, also persists among the veteran population.

“Part of what we deal with everywhere is the stigma of mental health. But maybe, with this population, it’s a little stronger-instilled: It’s seen as a weakness,” she explains, noting that mental-health-related issues the local office frequently sees include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, substance abuse, homelessness and unemployment.

• • •

Certain triggers can instantly make Plemmons find himself back in Iraq — or find parts of Iraq back in him.

He doesn’t like to go to the mall. “No way. Too many people.”

He always takes the seat closest to the wall. “If your back’s against the wall, nobody can be behind you.”

And he always thinks up an escape plan. “If something does happen, I’m going to go out that window.”

During his year as a military police officer at Camp Bucca, once the largest detainment center in Iraq, Plemmons adapted to his new environment. Now, however, the 27-year-old says he’s still in the process of adapting to post-Army life. “It’s a culture shock when you get over there; then it’s a culture shock when you come back.”

He continues, “I’ve been shot at. I’ve been attacked. I’ve lost a friend. I’ve been bombed. You lose all emotion over there ― except for a couple that will save your life.”

An outgoing manner wouldn’t have helped Plemmons when a roadside bomb blew up the bus that he and more than 40 detainees were riding in as it pushed toward northern Iraq. And by the time he returned home in the fall of 2005, Plemmons had become more distant, less talkative. Insomnia kept him awake nearly every night, and when it didn’t, his dreams made him long for a pill that could shut them down the way you turn off a TV.

Friends and family began to tell Plemmons he’d changed. But what hurt the most was when his best friend said Plemmons was no longer the “smoker and joker” he used to know. At that point, the young veteran began to understand how much he’d been weathered by war and morphed by mortar fire.

“There’s not one person in this world that wants to believe that they’ve changed. No matter how severe something could be, you don’t want to think of being the person who’s changed, especially if it’s in a bad way,” he maintains.

• • •

No one believed the 25-year-old soldier when she said her staff sergeant had sexually harassed her. He denied it, and when other soldiers accused her of lying, she dropped the matter. So when four of her fellow soldiers raped her in the barracks, she said nothing.

“I felt like I couldn’t go to anybody,” the veteran says now, speaking on condition of anonymity. “There shouldn’t be, but there’s a lot of shame.”

It would be more than 20 years before the Army veteran could begin to talk about what happened to her while serving as an administrative clerk at a base in Heidelberg, Germany, from 1980-83.

Being a victim of military sexual trauma, she says, “affects every relationship that you have.” It’s been 12 years since she was last romantically involved with anyone.

During the last fiscal year, she was one of the 884 victims of military sexual trauma treated at the Asheville VA hospital.

• • •

Shortly after Lapointe moved back to his family’s potato farm in Maine, his mother brought him what she thought was great news. “They’re having a celebration for veterans,” she told him excitedly. “You should put on your uniform.”

Silence.

“Where’s your uniform?”

“I can’t tell you,” Lapointe answered.

She kept pushing him, and he kept lamenting, “I can’t tell you.”

“I’ll press it for you,” she offered.

An anguished Lapointe struggled to find a gentle way to tell his mother that she couldn’t press a uniform he no longer had.

“Well, where is it?”

Sometime before, Lapointe had walked straight to the barn, taken off his uniform, and burned it in the iron barrel his father used to incinerate the trash.

“After the country’s response and the effects of war,” he says, taking two deep breaths, “I felt ashamed.”

Kevin Turner, director of Buncombe County’s veterans assistance office, says the complexity of the claims process can sometimes result in “unintended consequences.”

• • •

It took Plemmons three years to begin seeking help — and nearly two more before the Iraq War veteran actually got any. Still, he fared better than most local veterans who submit disability claims, particularly if they’re mental-health-related, says Kevin Turner, who heads up Buncombe County’s Veterans Assistance Office.

The county agency helps local veterans connect with the proper services within the federal VA system. “The claims process itself is very complicated. They don’t mean for it to be, but it is,” says Turner, a veteran who left active duty in August 2011.

Papers practically spill out of the thick, green folder Turner slaps on his desk. Wanting to really understand the timeline for the claims his office sends off to the VA for processing, Turner filed one himself, intentionally omitting information that might cause it to get special treatment (such as the fact that he’s a general officer and head of an office that serves vets).

“We submitted my claim as if I was Joe Blow,” he explains, opening the folder. “I submitted that in July of last year, and I have yet to be sent a request to have a physical.”

After the first 125 days (the federal agency’s stated goal for processing claims), Turner’s test case became part of the VA system’s massive backlog. As of Aug. 3, nearly two-thirds of the claims in the system — 500,062 out of 780,026 — were backlogged, the Veterans Benefits Administration reports.

Turner, however, worries more about what he calls “the unintended consequences.”

When Turner asked a veteran with severe PTSD to describe the event that had so terrified him, the soldier struggled to articulate it. But Turner knew from the man’s records that the traumatic event was a prison break in Afghanistan, which Turner knew about from his own time on active duty.

“I knew the dude was telling the truth,” he says. “We were going to push this thing. And then the gentleman kills himself before the VA ever gets all the paperwork together to process his claim.”

Pulling out his BlackBerry, Turner reads part of the daily list of military suicides that commanding officers receive. “Death of a soldier in Texas. Potential suicide; number 153 for the calendar year. On the same day, death of a soldier in Qatar. Asphyxiation,” he says, putting down his smartphone.

“That is the drumbeat that goes on,” he continues, pounding his fist on the table. “Not all of these people had PTSD. Some of them were dealing with depression; Some of them were dealing with just poor choices. You can’t put people in boxes, because there’s not boxes to describe it. It’s cross-symptomatic.”

• • •

Once her eyes adjusted to the light, none of the surroundings looked familiar. She wasn’t in the room she’d been renting from friends — and why was she lying in a hospital bed?

For eight days, the 56-year-old had been in a coma, the nurse explained; two doctors called her survival “a miracle.” But that alcoholic blackout successfully annihilated the memory the Army veteran would need in order to connect all the pieces: To this day, she doesn’t know how she tried to kill herself, or even why.

For her, it remains one of the lowest moments in a life she describes as “tragic, yet blessed.”

“I guess I just hit rock bottom,” she says.

Soon after her attempted suicide, the veteran enrolled in a substance-abuse program and mental health services in Salisbury, N.C., where there’s a VA facility. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder and PTSD (the latter stemming from her military sexual trauma in Germany). But when she returned to Asheville, she was homeless. Having nowhere else to go, she wound up at Steadfast House, Asheville Buncombe Community Christian Ministry’s facility for homeless women, children and families. The roughly 33-bed shelter reserves 10 beds specifically for female veterans.

Sadly, this veteran’s story of PTSD and military sexual trauma is not uncommon among the clients who seek shelter at Steadfast House, Director Donna Wilson reveals.

“A lot of times, women experience being raped or molested before they go into the military. Sometimes they go into the military to escape that and then, unfortunately, something happens in the military also,” she explains. “Our society is just now kind of accepting that that’s happening, but our women still are very private and scared to talk about it.”

After returning home from Vietnam, Ron Lapointe begged his brother to send him his drum kit. Those drums, Lapointe says, “really saved my sanity.”

• • •

Talking about Vietnam, Lapointe maintains, isn’t going to help. “I don’t want to sit in a room of vets, particularly combat vets, and share war stories,” he says. “Why relive something you don’t want to relive?”

That makes sense to psychologist George Lindenfeld, a veteran himself. Rather than relying on strictly talk-based psychotherapy, Lindenfeld combines biofeedback principles with psychology to help local veterans with PTSD heal.

“Forget the symptoms. Imagine that a trauma resets a pathway in your brain,” says Lindenfeld, who assesses veterans’ disability ratings for a company that contracts with the VA. In other words, whenever something occurs that resembles the traumatic event, it will trigger an emotional reaction over which the person has no control.

“It’s analogous to a light switch,” Lindenfeld explains.

Instead, he targets the uncomfortable memory in the client’s mind, using sound to disrupt that toxic response pattern. The beauty of the treatment, says Lindenfeld, is that it “allows you to focus internally. You don’t talk to the therapist about what you’re doing.”

Veterans, he emphasizes, need more therapeutic options. Otherwise,“There are too many guys that just aren’t going to get what they need.”

• • •

Weeks after returning from Iraq, Plemmons and about 80 other soldiers piled into a big classroom. Taking his seat in the back row alongside other guys his age, Plemmons watched an officer wheel a projector into the room.

“These are the things you need to look out for,” the officer told the group, as the warning signs for PTSD, traumatic brain injury and suicide flashed on the screen. But while other soldiers joked around in between the slides, Plemmons thought, “I feel like that.”

Following orders, Plemmons got in a line that led to a row of tables where psychologists were waiting, armed with stacks of pamphlets. But when he got toward the front of the line, he could hear what the men already seated at the tables were saying.

“They were all just telling the psychologists what they wanted to hear,” he recalls. So he stuck to the script with the shortest run time: a repetition of noes.

At his 10-year high school reunion last month, however, the 27-year-old veteran learned that his best friend’s brother had recently joined the Air Force and is currently deployed overseas.

And though Plemmons had no pamphlet, no panel of psychologists or PowerPoint presentation, suddenly, he opened up.

“When you start seeing him not wanting to talk to you, start getting aggravated over small things, start talking about things that you don’t think would be right, you need to tell him to get help now,” Plemmons told his friend.

Stopping his story abruptly, Plemmons says: “These people aren’t crazy. They’re just unheard.”

— Caitlin Byrd can be reached at cbyrd@mountainx.com or 251-1333, ext. 140.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.