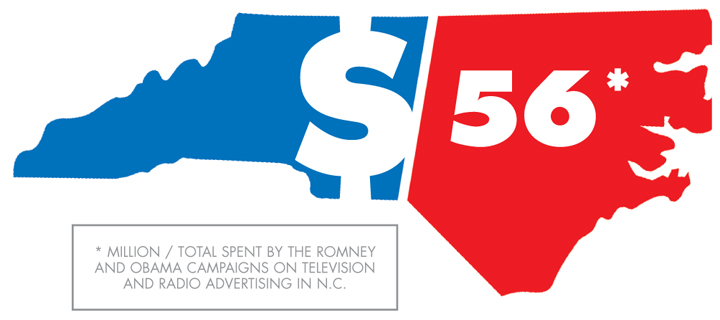

It’s no secret that money and politics go hand in hand. Since March 19, the Romney and Obama campaigns have spent a combined $56.5 million on radio and TV ads in North Carolina alone, according to NBC News. But money is also pouring into local political races, as individuals and special-interest groups invest in the candidates they want to see win in November.

Some people give because they agree with a candidate’s stances on the issues or know them personally. Others hope their investment yields returns in the form of precious access and influence on the candidate’s behavior once elected.

Amid a splintered media landscape and voters’ shrinking attention spans, most candidates see money as key to getting their message to the masses. It pays for the TV ads they want you to see, the postcards you get in the mail, the yard signs and more.

But sometimes the money behind the marketing says as much about a given race as the ads themselves, offering insights into candidates’ views — not to mention their chances of winning. Here’s a look at who’d given what to which local candidates as of June 30, the most recent data available.

Access and influence

Western North Carolina’s congressional races are seeing the biggest infusions of cash.

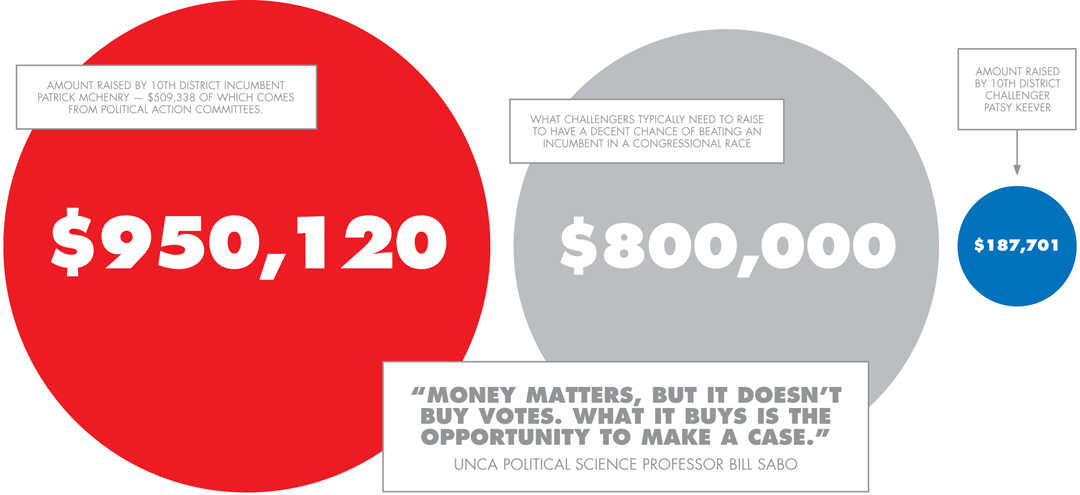

In the 10th District, which now includes most of Asheville, incumbent Republican Patrick McHenry has amassed a huge financial advantage over Democratic challenger Patsy Keever.

In the 10th District, which now includes most of Asheville, incumbent Republican Patrick McHenry has amassed a huge financial advantage over Democratic challenger Patsy Keever.

As of June 30, the closing date for the latest reports filed with the Federal Election Commission, the Gaston County resident had raised $950,120 for this year’s campaign — more than five times the $187,701 Keever collected during the same period.

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, about 54 percent of McHenry’s total haul came from political action committees — groups representing particular interests and working to defeat or elect candidates. For Keever, that figure was 5 percent.

“We expected Patrick McHenry to have more money and are not surprised by the amount he’s raised,” the Keever campaign wrote in an email to Xpress. “Nor are we surprised at where more than half of his cash came from,” the email continued, noting that PACs from Rep. Eric Cantor of Virginia and financial-services firms Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley each contributed about $10,000 to McHenry’s campaign. “This flood of money is turning people off and threatening democracy,” the email asserted.

Now in his fourth term, McHenry serves on the powerful House Financial Services Committee, which drafts and reviews all federal legislation involving the banking and financial-services industries as well as monetary policy. His top three donors this election cycle are Wells Fargo, Advance America Cash Advance Centers and the American Bankers Association, the Center for Responsive Politics reports.

But the McHenry campaign dismissed the implication that those donations might influence his voting record.

“Patrick has always considered any support for his campaign a recognition of his principles and ideas, not the other way around,” the campaign wrote in an email. “We’re proud to have such broad support from across the district.”

Still, the boundary between the two isn’t always so clear-cut, notes UNCA political science professor Bill Sabo.

“It’s not so much that the banking interests buy support. What they’re doing is, they’re giving money to someone who has a track record of being favorable to banking interests,” he explains. “Money matters, but it doesn’t buy votes. What it buys is the opportunity to make a case. … What a lobbyist needs is access: the ability to pick up the phone and talk to the representative.”

Sabo stresses, however, that money and access don’t guarantee results. “If you’ve got a lousy case, all the contributions in the world are not going to get somebody to support you.”

Overwhelming advantage

Special interest groups, says Sabo, often act like investors, betting on who they think will win. The 10th District, he notes, is conservative, and Keever has little name recognition outside Buncombe County, where she’s served as a state legislator and county commissioner.

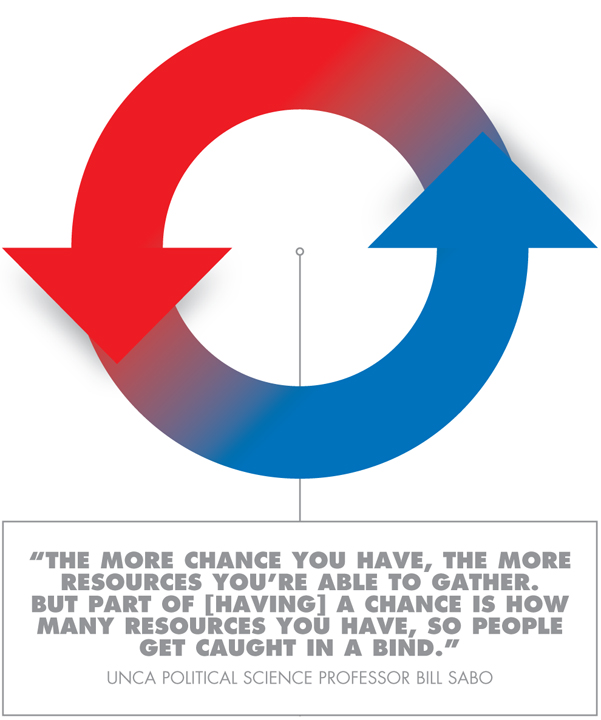

“The more chance you have, the more resources you’re able to gather,” Sabo explains. “But part of determining whether you have a chance is how many resources you have, so people get caught in a bind. … You have the chicken-and-egg problem.”

On average, notes Sabo, challengers nationwide need to raise about $800,000 in order to have much chance of toppling an incumbent. And even if they meet that mark, challengers have only a one-in-three shot, he says, adding that incumbents facing a challenger with less money win re-election 90 to 95 percent of the time.

Based on that history, Sabo says flatly, “McHenry’s already won this election. What he wants to do is scare off a serious opponent in two years.” The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee isn’t giving Keever much support, considering the contest a lost cause, he says.

But Keever’s people argue that the race doesn’t fit the historical model. McHenry, they maintain, is largely unknown to voters in the newly added parts of the retooled district, including Buncombe and Polk counties. They also cite the fact that Keever handily defeated Asheville Mayor Terry Bellamy in the May primary despite a sizable financial disadvantage.

But Keever’s people argue that the race doesn’t fit the historical model. McHenry, they maintain, is largely unknown to voters in the newly added parts of the retooled district, including Buncombe and Polk counties. They also cite the fact that Keever handily defeated Asheville Mayor Terry Bellamy in the May primary despite a sizable financial disadvantage.

Blue America, a progressive national advocacy group, has recently mounted a fundraising drive for Keever. McHenry, however, has also continued raising money.

No incumbent

With Rep. Heath Shuler not seeking re-election in the 11th Congressional District, both Democrat Hayden Rogers and Republican Mark Meadows appear poised to raise more than $1 million.

Rogers, Shuler’s former chief of staff, had raised about $491,000 as of June 30. Meadows, a Cashiers real estate developer, had collected about $229,000; he’d also lent his campaign about $264,000. At the time, his resources were strained by a July 17 primary runoff against Vance Patterson.

Rogers, notes Sabo, “has a Rolodex of contributors” because he’s “hooked into [Shuler’s] network.” According to the Center for Responsive Politics, political action committees account for roughly 37 percent of Rogers’ total contributions, compared with a mere 7 percent for Meadows.

Rogers’ biggest contributors included Phillips & Jordan, a national construction company specializing in transportation infrastructure, oil and gas projects, landfills and more ($15,750); and the Murphy Electric Power Board, a WNC utility ($10,400). Cecil Bothwell, Rogers’ opponent in the Democratic primary, raised far less money, and Rogers collected 55 percent of the vote despite Bothwell’s lambasting him for accepting thousands of dollars from the payday-loan industry, which critics say engages in predatory practices.

McHenry has also received thousands of dollars from the industry, which is banned in North Carolina. To date, Keever hasn’t raised the issue.

As of June 30, Meadows’ top donors included Colson Hicks Eidson, an injury-litigation law firm based in his native state of Florida, as well as Lupoli Construction in Highlands and the American Society of Anesthesiologists, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Two years ago, Shuler raised more than $1.3 million to defend his seat against a challenge from Hendersonville businessman Jeff Miller, who raised about $795,000. Like Rogers, Shuler’s top contributor was Phillips & Jordan, which gave $15,800 to his campaign, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Shuler serves on the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

But despite Rogers’ fundraising efforts, his electoral prospects are far from clear. Last year’s redistricting removed Asheville from the district, making it more conservative. Plus, “a pseudo incumbent is not an incumbent,” says Sabo, predicting that the next Federal Election Commission reports, due Oct. 15, will show a lot more money from across the country flooding into both campaigns.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if it ran over $3 million total,” he says, noting that in rural districts like the 10th and 11th, it takes more money to get a message out to voters, because there’s no centralized media market.

State races

Incumbents in the N.C. General Assembly also seem to be dominating the money scramble.

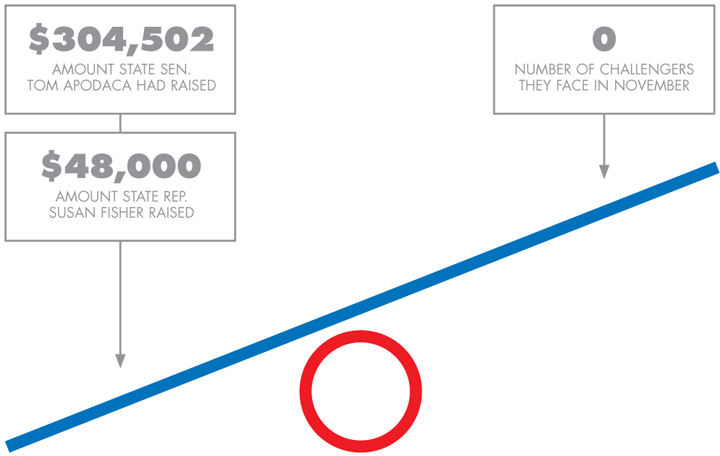

State Sen. Tom Apodaca, whose District 48 includes southern Buncombe County, had raised a whopping $304,502 as of June 30 — even though the powerful five-term Republican has no challenger.

His biggest donors (each gave $4,000) included political action committees representing Blue Cross and Blue Shield of N.C., GlaxoSmithKline and Citizens for Higher Education, which advocates for UNC-Chapel Hill. Apodaca chairs and co-chairs various committees, including the Senate’s Insurance Committee and the Appropriations Committee on Higher Education.

Senate Minority Leader Martin Nesbitt, a Democrat who represents the rest of Buncombe County (including Asheville), raised $138,609 during the same period. Nesbitt’s Republican opponent, R L Clark, whom he’s defeated in the last three elections, raised just $6,793 (including $2,500 in self-funding). Nesbitt, who also serves on the Appropriations Committee on Higher Education, received $2,000 from the Citizens for Higher Education PAC. Sabo says it’s common for competing candidates to get donations from the same special-interest groups looking to “hedge their bets.”

Democratic Rep. Susan Fisher had raised $48,000 as of June 30 despite facing no challenger in District 114, which covers most of Asheville.

Incumbents can save unspent funds for future campaigns or give it to other candidates.

Moffitt vs. Whilden

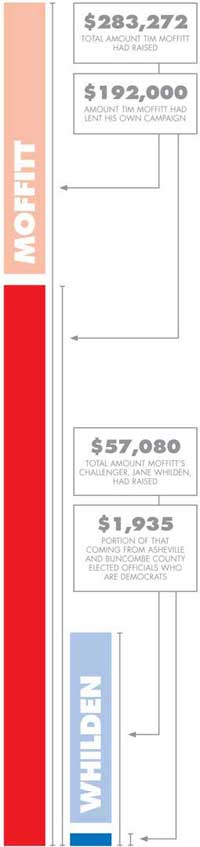

One of the most hotly contested local contests is playing out between Republican Rep. Tim Moffitt and Democrat Jane Whilden. It’s the only race that’s seen a marketing campaign by an outside group not officially tied to a candidate or party.

According to FollowNCMoney.org, a project of the nonprofit Institute for Southern Studies, the conservative Carolina Business Coalition Education Fund has already spent $47,616 on Moffitt’s behalf. The group is not required to reveal its donors; its board members have close ties to the textile, banking, pharmaceutical and tobacco industries, among others. To date, the fund has spent $347,180 on political advocacy statewide, according to the website.

Moffitt, who owns an executive-search and management-consulting business, had lent his campaign $192,000 as of June 30, according to the latest finance reports. Political action committees chipped in another $50,835, including sizable amounts from the Alliance for Access to Dental Care, N.C. Manufactured and Modular Homebuilders PAC and the N.C. Beer and Wine Wholesalers Association PAC.

Whilden, who beat Moffitt in 2008 and served one term in the Statehouse before losing to him in 2010, had gotten most of her donations from individuals, who accounted for about $40,000 of her $57,080 total. Whilden’s biggest individual donor was fellow Biltmore Forest resident Terry Van Duyn, a Democratic candidate for the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, who gave $1,050.

Moffitt has often feuded with local Democratic officials, many of whom gave money to Whilden. Asheville Vice Mayor Esther Manheimer and City Council member Jan Davis each gave $250; Board of Commissioners Chair David Gantt gave $700, Commissioner Holly Jones kicked in $135 and Sheriff Van Duncan donated $500.

Holding onto District 116, which encompasses the most conservative parts of the county and stretches from Arden in the south to Sandy Mush in the northwest, is strategically important for Republicans, notes Sabo.

“Moffitt’s become a symbol, and symbols tend to attract more attention,” Sabo observes. “And as they attract more attention, money’s going to roll in, because you don’t want to lose this highly visible, symbolic race. It gives Moffitt an advantage, because he’s better connected with donors across the party.”

In the race for District 115, which stretches from Weaverville down to Black Mountain and Fairview, Republican Nathan Ramsey ($17,232) and Democrat Susan Wilson ($15,327) were about evenly matched as of June 30. Neither had raised significant funds from PACs.

Buncombe County contests

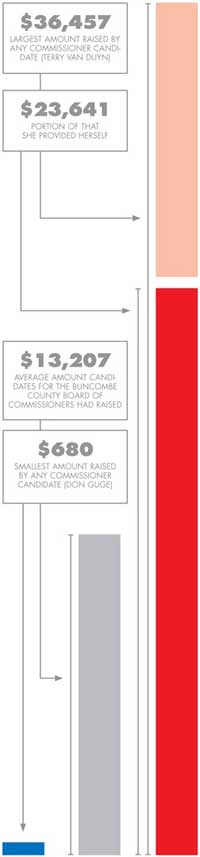

With so many hotly contested races on the ballot, candidates for the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners can have a hard time competing for funds and attention. But at the local level, money isn’t always the deciding factor.

In the May Republican primary, for example, private investigator J.B. Howard, a candidate for board chair, soundly defeated businesswoman Glenda Weinert despite being out-funded by a 15-1 margin. Howard spent hours shaking hands at Republican gatherings and introducing himself to shoppers outside Home Depot, focusing on retail politicking instead of advertising, he says.

But it’s far from clear whether he’ll be able to replicate that success in a general election with a much broader electorate heading to the polls. And as of June 30, incumbent Democrat David Gantt had raised $25,715 compared with Howard’s $1,240.

New this year are district elections for all commissioner races except the chairmanship. Moffitt, who spearheaded the change in the General Assembly, said it would enable candidates with less money to compete by requiring them to appeal to a smaller geographic area and fewer voters.

It’s too soon to say if that will prove true, but District 2 Republican Mike Fryar (who’d collected $10,467 as of June 30) says that despite the smaller territory, he’s on track to raise more money than he did in his failed bid four years ago. Fryar says he prefers the district system, cautioning, “It still takes a good bit of money.”

As of the latest reports, District 1 Republican Don Guge had raised the least of any commissioner candidate ($618). District 3 Democrat Terry Van Duyn had raised the most ($36,457), with $23,641 coming out of the retired systems analyst’s own pocket.

Under the countywide election system in place in 2008, Democratic commissioners Holly Jones and Carol Peterson each raised around $60,000. And district elections, notes Sabo, present their own challenges.

“On one hand, you have a smaller area. But on the other hand, that makes any kind of investment in television, radio, kind of wasteful,” he explains. “You’re getting your message out to a lot of people who may get excited about your candidacy, only to find out you’re not in their district.”

PACs have mostly stayed out of the commissioner races. District 3 Republican Joe Belcher is one of the few candidates to receive PAC money so far.

A regional manager for Clayton Homes, Belcher received $250 from the N.C. Manufactured and Modular Homebuilders PAC, $100 from former Clayton Homes owner James Clayton and $250 from current CEO Kevin Clayton. Mike Teem, assistant vice president at Phillips & Jordan, chipped in $500.

Belcher says he wants to change county zoning rules to allow mobile homes in more areas. But he downplays the impact of donations, pointing out that they account for a very small percentage of his campaign funds. He’d raised $18,179 as of June 30, and two-thirds of that was self-financing.

“I’m getting money from friends,” he reports. “I will accept no money from anybody who even looks at me like they want something, because it’ll never happen — period.”

Still, Belcher finds fundraising the most challenging part of his first bid for elective office. “It’s very hard for people like us who have never been involved in politics,” he notes. “You’ve just got to realize it’s for the good, and it costs money.”

Great comprehensive report, and I love the infographics. Thanks, Jake. What an undertaking.

Appreciate the extensive information prior to the beginning of the early voting period.

thanks

“”The money conundrum: Campaign finance and local elections” sets a new bar for WNC reporting standards!” – The People

“500 Star Rating!” – Liberal Democracy