Danny Dragonetti had been clean for three years after kicking a drug habit that started in middle school. But in a moment of weakness last November, alone in his Black Mountain home, he once again injected heroin into his veins.

The culinary arts student, known for his fun-loving, generous and kind nature, died of an overdose at age 26, yet another victim of what health officials say is a burgeoning epidemic.

“He died instantly,” says his father, Dean Dragonetti. “We’re not sure what happened, but our best guess is he relapsed to deal with anxiety. He was supposed to join a co-worker that afternoon. He didn’t show up, and the co-worker went to check on him and found him dead in his room.”

Anna Huneycutt used needles to inject prescription opiates, says her mother, Julie Huneycutt. The 20-year-old Henderson County woman died of an overdose in 2010.

“She was definitely a needle addict,” she says. “She was shooting up the pills. It’s the same thing as heroin basically. Because we’re tightening up on prescribing policies, that’s raised the price of these pills significantly, and heroin is just a much cheaper alternative.

“It’s been devastating. To me it’s just unbelievable. It’s like we can’t stem this tide.”

National trends hit home

The two are among the many thousands in the U.S. to succumb to the lure of heroin, a problem that law enforcement and public health officials say is on the rise — ironically, due to efforts to reduce prescription opiate abuse.

Heroin-involved overdose deaths across the country nearly doubled between 2011 and 2013, when more than 8,200 Americans lost their lives to the drug, according to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (also known as the CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration.

“Heroin use is increasing at an alarming rate in many parts of society, driven by both the prescription opioid epidemic and cheaper, more available heroin,” says CDC Director Tom Frieden. “To reverse this trend we need an all-of-society response.”

According to the report, more than a half-million people used heroin in 2013, up nearly 150 percent since 2007. Heroin use remained highest among poor young men in urban areas, but the increases were spread across all demographic groups, including women and people with higher incomes — groups associated with the rise in prescription painkiller use over the past decade.

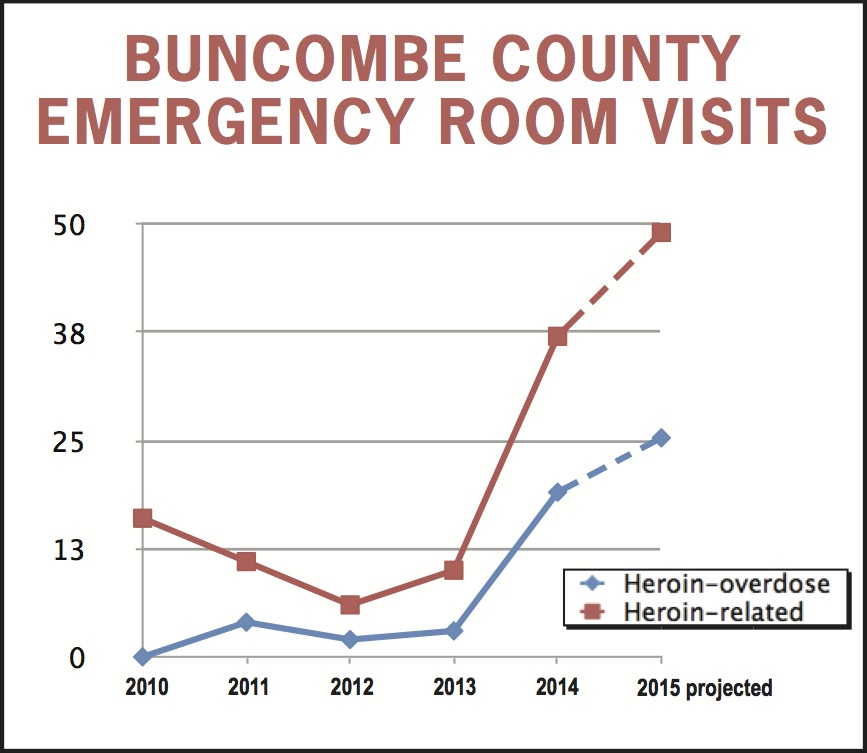

The effects have been felt locally, as visits to hospital emergency departments in Buncombe County for heroin overdoses increased dramatically over the past 18 months, according to data from the N.C. Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool, a state surveillance system that monitors emergency department visits. There were no such visits in 2010, four in 2011, two in 2012, three in 2013, 19 in 2014 and 16 this year as of Aug. 19.

“Heroin is highly addictive, and there is always the risk of a fatal overdose,” says Dr. Jennifer Mullendore, medical director at the Buncombe County Department of Health and Human Services. “The impacts of heroin use are widespread and not only include poor health outcomes. Heroin use takes a toll on those around the user and the community as a whole.”

Chronic users can develop serious health conditions such as heart and heart valve infections, abscesses and kidney or liver disease, Mullendore says. Heroin also may contain toxic contaminants or additives, and babies exposed to it in the womb can be born premature and underweight.

Law enforcement taking notice

Asheville is also seeing an upsurge in heroin use and overdoses, says Sgt. Steve Riddle, supervisor of the the city police department’s Drug Suppression Unit. The department began tracking overdoses March 29, 2014, as they became strikingly more prevalent. Through July of this year, officers responded to 25 overdoses, although the city’s tally doesn’t distinguish what type of drugs caused them.

“We’ve definitely seen an increase” in heroin use, Riddle says. “This is a serious problem. This drug is killing our kids. We need to do everything possible that we can to combat this through treatment, the judicial system and education.”

According to Riddle, the heroin epidemic doesn’t appear to be concentrated in any particular areas of the city or socioeconomic spheres — echoing the CDC’s national findings. “It’s very widespread,” he says. “There’s actually no particular one social group or status. We’re seeing heroin use in teenagers and we’re seeing heroin use in older adults.”

Asheville Police Department drug investigators have made arresting heroin distributors their top priority, Riddle says. “We’ve made some of these known heroin dealers as our targets and we’re working those cases as we can,” he says. “Over the past couple of months it’s become our main thrust.”

Unintended consequences

Like others, Riddle attributes the rise in heroin use to the increasing difficulty in obtaining such prescription opiate drugs as oxycodone. He says hospitals have largely stopped dispensing the painkillers during emergency room visits, and a new monitoring program allows pharmacies to limit prescriptions.

“So, one person can’t go to a pharmacy, get a bunch of oxycodone and then go to another pharmacy and get it like they were able to do in the past,” Riddle says. “Because of those restrictions, the pills are getting harder to get. We see that because the street prices for the pills are going up as well.”

Heroin has become cheaper than prescription painkillers and easier to obtain, he says. “The addict is now going to the heroin,” he says. “It’s kind of a void that’s been filled.”

The CDC study backs up his observations, saying that people who are addicted to prescription opiates are 40 times more likely to use heroin.

Xpress took a look at opioid abuse and the resulting rise of heroin as prescription pills become harder to obtain in a June 9 article “To the brink and back“, which also detailed some of the reasons people find themselves falling into opioid addiction and the health hazards of opiates.

“We are priming people to addiction to heroin with overuse of prescription opiates,” Frieden says. “More people are primed for heroin addiction because they are addicted to prescription opiates, which are, after all, essentially the same chemical with the same impact on the brain.”

Riddle says he’s been working with the Partnership for Substance Free Youth of Buncombe County on prevention efforts and has talked to civic groups and other organizations about the problem. He’s not alone in reaching out to others.

“The scary thing for me is, what used to be a taboo for us when I was growing up, was sticking a needle in your arm,” he says. “No one would think of something like that. And to a lot of youth that’s no longer a taboo. It’s nothing to stick a needle in your arm, and I’m like, ‘This is crazy’.”

Victims’ families trying to save others

In the wake of her daughter’s death, Huneycutt helped found Hope Rx of Henderson County, a group dedicated to fighting prescription drug abuse. Its member organizations include hospitals, law enforcement, faith groups and others in the community.It’s disheartening that making prescription painkillers harder to get has resulted in more heroin addiction, she says.

“You do what you can,” she says. “You know that by eliminating one problem it can create another, so you just have to find ways to address it across the board. And we know that one of our biggest problems is the way that we treat addiction, that we’re very lacking in treatment, that we’re very punitive to people who do abuse drugs. We need to be working toward helping people find coping skills instead of treating them like criminals and incarcerating them and not getting the treatment they need.”

Danny Dragonetti’s father, who is studying to become a substance abuse counselor, says his son was a quiet and sensitive child who was musically inclined. He was enrolled in the culinary arts program at Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College when he died.

“He had the capacity to be silly and fun-loving, very creative,” he says. “He was a very gifted chef and he was a gifted singer-songwriter. If you were in need, he’d give you his last dollar.”

But around age 14, Danny started using drugs. Over the years, he was arrested three times on drug-related charges.

“I think it started with pot and alcohol,” the senior Dragonetti says. “Like any other addict, his disease progressed. Somehow somebody introduced him to opiates, and he battled opiates probably six years. As with many other addicts, he had to experience the pain and loss and isolation of the disease. We were ecstatic when about four years ago he came to us and said, ‘I’m really ready to do something with my life, and I need to get help with my disease.’ ”

Danny’s father said his son spent a year in a residential substance abuse treatment program and stayed sober about three years. He shocked to learn that his son had relapsed and died of an overdose.

“We had seen him 48 hours prior to his death,” he says. “My wife and I had lunch with him, and he looked great and sounded good. He was taking a full load of classes at A-B Tech and he was working part time and he was in recovery.”

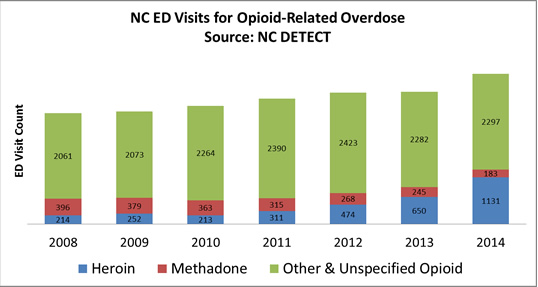

The inclusion of Methadone as a somewhat wide-appearing band in the graph of drugs that are sources of overdose begs the following observations:

1) The number of overdoses attributed to Methadone has decreased every year that data is displayed.

2) For the most recent year, 2014, Methadone was responsible for only .05% of all overdoses.

As a healthcare professional, I have been frustrated to see physicians of in-patients deny clients of Methadone clinics their out-patient Methadone on the false assumption that it is just another abused opiate or a mere “crutch”, and that addicts should “man up” and go cold turkey. I would hope that more physicians will educate themselves on the value of this very safe and seldom abuse opiate alternative.

Decriminalize, Access to Treatment, including Methadone or Suboxone free of charge, and implementation of the Housing First Model to help addicts off the street and into a supportive (vs.punitive) environment. The upfront costs would easily be offset by the savings.

This article does not address overdose prevention laws in NC…. Please note them below…

OVERDOSE PREVENTION LAW IN NC

SB20 911 Good Samaritan/ Naloxone Access law, effective April 9, 2013, states that individuals who experience a drug overdose or persons who witness an overdose and seek help for the victim can no longer be prosecuted for possession of small amounts of drugs, paraphernalia, or underage drinking. The purpose of the law is to remove the fear of criminal repercussions for calling 911 to report an overdose, and to instead focus efforts on getting help to the victim.

The Naloxone Access portion of SB20 removes civil liabilities from doctors who prescribe and bystanders who administer naloxone, or Narcan, an opiate antidote which reverses drug overdose from opiates, thereby saving the life of the victim. SB20 also allows community based organizations to dispense Narcan under the guidance of a medical provider. As a result, officers may encounter people who use opiates and their loved ones carrying overdose reversal kits that may include Narcan vials, 3cc syringes, rescue breathing masks and alcohol pads.

Full text of SB20 is available here:

http://openstates.org/nc/bills/2013/SB20/documents/NCD00022391/

As of August 1, 2015, a person who seeks medical assistance for someone experiencing a drug overdose cannot be considered in violation of a condition of parole, probation, or post-release, even if that person was arrested. The victim is also protected. Also, the caller must provide his/her name to 911 or law enforcement to qualify for the immunity. Pharmacists are now immune from civil or criminal liability for dispensing naloxone to people at risk of an opioid overdose.

The bill enabling this law was called SB154, Clarifying the Good Samaritan Law. Full text is available at:

http://www.ncleg.net/gascripts/BillLookUp/BillLookUp.pl?Session=2015&BillID=S154

Sad to see no mention of the great work of Buncombe County EMS and North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition have been doing saving lives from opioid overdoses with naloxone in Buncombe County. EMS has been saving lives since the 70s with the wonder drug naloxone and North Carolina Harm Reduction, which provides the opioid reversal drug to the community, has reversed 228 since 8/1/2015. This is more community overdose reversals than any city in North Carolina.

Naloxone (also known as Narcan®) is a prescription medicine that reverses an opioid overdose, which can be caused by prescription analgesics (e.g., Percocet, OxyContin), and heroin. Naloxone will only reverse an opioid overdose, it does not prevent deaths caused by other drugs such as benzodiazepines (e.g.Xanax®, Klonopin® and Valium®), bath salts, cocaine, methamphetamine or alcohol. However, naloxone may also be effective for polysubstance overdoses such as a combined opioid and alcohol overdose. It cannot be used to get high and is not addictive. Naloxone is safe and effective; emergency medical professionals have used it for decades. For more detailed information, visit http://www.drugs.com/pro/naloxone.html

The amount of reversals are from 8/1/2013-9/1/2015

Xpress reported on the remarkable work to save lives in OD cases in Buncombe. Here’s the link http://mountainx.com/news/to-the-brink-and-back-opioid-abuse-and-treatment-in-wnc/

Thank you Jeff Fobes.