Never underestimate the weather. Sure, the French Broad River crested a tad above flood stage on May 27 at Blantyre, near Brevard. Yes, May has brought us more than 8 inches of rain (that’s nearly a record, twice what’s been typical since 1971, and definitely greater than 2008’s paltry 0.81 inches, according to the National Climatic Data Center).

But ask State Climatologist Ryan Boyles about the likelihood that we might still face drought conditions this summer and he cites the official long-term forecast for North Carolina, which says it’s equally likely that conditions will be wetter than usual, about normal or drier than usual. “In other words, they don’t know,” says Boyles, with the barest hint of bone-dry humor.

Still, the state is drought-free for the first time in several years. “We’re quite relieved,” says Boyles, who also directs the State Climate Office (and, incidentally, earned his doctorate researching summer-rain patterns in North Carolina). “Some of us, for the last three years, have been living and breathing drought, and we do have other work that we do.”

Headquartered at N.C. State University in Raleigh, the Climate Office provides such services as weather- and climate-based modeling that help strawberry growers plan for freezing conditions, water providers adjust for drought, or electric utilities get ready for a heat wave. The office also assists tourism agencies, the transportation industry, public-health agencies and any other sector affected by weather and climate—in a word, just about everyone.

“It’s a strong service mission. We’re not just doing research but helping the public,” says Boyles, a Durham native who wanted to combine science with service in his career. His partners at the Southeast Regional Climate Center—based at nearby UNC-Chapel Hill—are concentrating on how climate affects human health, such as the effects of heat waves on the elderly, for example. “Climate plays a role in our lives,” he continues.

Of course, he reflects, “There’s a lot of science and a lot of data, but how do you make it useful?” Media reports often mention year-to-date rainfall deficits, but Boyles says those are near meaningless. In trying to make sense of all the available data, those deficits—the negative difference between current conditions and prior-year seasonal norms—are the last thing scientists consider. Have we experienced less rain than usual in the past month? No. For the past three years? Yes, says Boyles. “A short-term dry spell affects the vegetation; a long-term one affects water supplies.”

When trying to forecast summer water levels, it’s more important to gauge whether ground water has recharged, he explains. Winter is typically when our region gets the precipitation needed to do that, but this past January was dry, raising scientists’ concern that the drought would continue, Boyles recounts. March, April and May rains have alleviated the situation, but it takes six months for ground-water reserves to “show a response to rain events,” he points out.

Furthermore, heavy rains are also problematic, because the water will wash rapidly downstream rather than seeping into ground-water supplies, though it will help replenish surface-water supplies such as reservoirs. And in the mountains, quick, heavy rains raise the specter of landslides. “It’s possible to have floods and drought at the same time,” says Boyles. “You can see flood warnings and think the drought is over”—but it might not be.

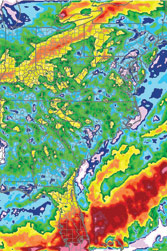

In the Southeast as a whole and in Western North Carolina in particular, summer weather varies greatly: While Asheville is probably the driest part of the entire state, nearby Brevard and Lake Toxaway are among the wettest, says Boyles, noting, “Asheville sits in a rain shadow.”

“Draw a hill,” Boyles instructs. “As wind and rain hit the hill, they can’t go through it, so they go over, raining on the way up to the top of the ridge. But as that air crests the [top], it sinks, tends to cool and is drier.” When moisture comes up from the Gulf of Mexico, Asheville lies on the drier, leeward side of the mountains, while Brevard and environs are on the rainy, windward side.

Asheville is fortunate to have a large reservoir from which to draw drinking water during dry spells. Smaller ground-water-based systems, however, remain vulnerable should the drought recur this summer and fall (November is typically the driest month), says Boyles. Last spring and early summer, water levels were good, but they kept dropping as fall approached; in late August, the French Broad reached its lowest recorded levels ever, he points out.

So predicting what’s coming is a bit of an educated guessing game, though we’re fortunate to have the Regional Climate Center, Boyes’ Raleigh office and the National Climatic Data Center in our corner. Says Boyles, “We’re the best fortunetellers out there.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.