By Andrew R. Jones, Sally Kestin and John Maines

They are among dozens of people who cycle through the Buncombe County Detention Center, in and out, again and again. They’re arrested, released, and arrested again, sometimes the same day.

Their crimes for the most part: drinking in public, sleeping in a business entryway, asking for money on street corners, and being drunk and disruptive.

Booked into jail on low-level offenses, they’re released in a few minutes to a few days, and the cycle begins again.

“The guilt or innocence of the person is somewhat irrelevant,” said Sam Snead, the Buncombe County Public Defender. “The goal is to get them off the streets and into the jail because there’s no other place to go.”

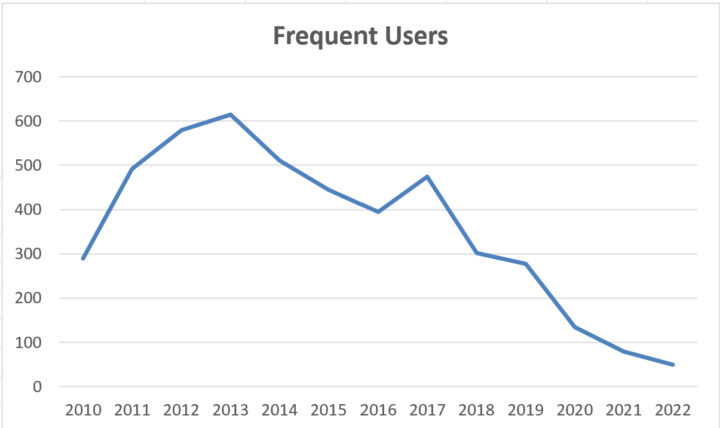

Asheville Watchdog examined Buncombe jail booking data from 2010 through 2022 and found 55 people with at least 50 arrests. Fourteen of them — including White and Fox — have been arrested 100 times or more.

Those 55 people accounted for 24% of all the charges of “begging for money” during that time, 20% of all the intoxicated and disruptive charges, 18% of open container violations, and 13% of the second-degree trespassing charges.

Their familiar faces in and around downtown add to a perception that Asheville has become less safe. A core group of people are responsible for a disproportionate amount of these crimes, and the cycle continues because local and state governments have failed to adequately invest in treatment, housing and alternatives to arrest.

Expensive to Buncombe taxpayers

The revolving door of the criminal justice system in Asheville and Buncombe County is frustrating to many involved and expensive to taxpayers.

Asheville Watchdog determined that repeatedly jailing the 55 people has cost at least $3.3 million over the 13-year period examined. The estimate is based on court costs provided by the state for low-level misdemeanors, $63 per case, and the reimbursement rate the federal government pays the county for the cost of housing an inmate in the Buncombe jail, $114 a day.

“Trying to fix the mental health problems of the world with the jail, with the criminal justice system, is like fixing a car with a sewing machine,” said Michael Casterline, an assistant public defender. “It just doesn’t work.”

When The Watchdog showed Casterline the list of “frequent users” of the jail, he said he recognized the names on it. Many are or have been unhoused and have mental illnesses, often combined with drug or alcohol addictions, he said.

“They get arrested because they’re places where people are bothered by them being there, not because they’re bothering people,” Casterline said. “They can’t be in the public parks because they’ve been trespassed from the park. They can’t be anywhere else.”

“They’re being arrested for things that probably aren’t charged for anybody [else],” he said. “Tourists walking around downtown drunk don’t bother people, and they don’t get arrested.”

Downtown merchants and workers have complained of reporting criminal behavior to police only to see the offender arrested and quickly released.

More than two-thirds of the time, the people with 50 or more arrests got out of jail in three days or less, and 40% of the time they were out within 24 hours, according to booking data reviewed by Asheville Watchdog.

Under North Carolina law, the maximum penalty for these types of crimes, Class 3 misdemeanors, is 20 days in jail, regardless of the number of prior convictions.

“I’ve been seeing these people for years, coming through and coming through and coming through,” Casterline said.

Housing with significant support is the only solution he’s seen work, reducing arrests. But even then, Casterline said, if “they lose their housing for some reason, it just kind of starts all over.”

‘Born with a disease’

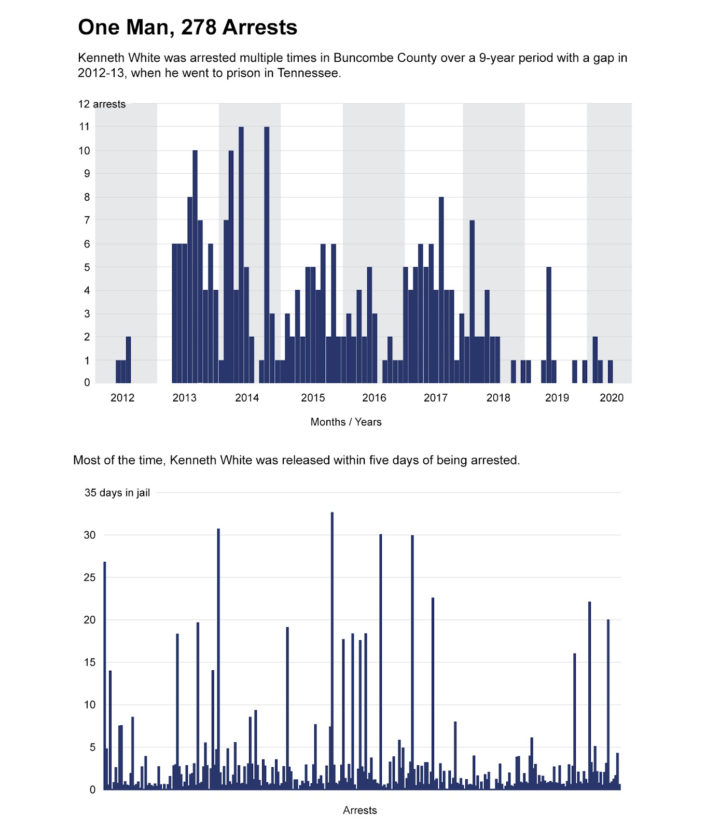

Kenneth White is the most arrested person in Buncombe County, according to jail data since 2010. His complete criminal record, dating to at least 1989 and spanning two states, puts his total arrests at more than 550, Asheville Watchdog found.

Raised in Hawkins County, Tennessee, White, one of eight children, spent most of his childhood in foster care due to his “parents’ alcohol abuse,” according to a 2020 guardian ad litem report filed in Buncombe County court.

White, now 61, became an alcoholic and wound up on the streets in Knoxville.

His sister, Cathy Morgan, told Asheville Watchdog, “Mom and dad were both alcoholics and I think he was kind of just born with a disease.”

Cheryl Lawson, Morgan’s daughter and White’s niece, told the guardian she had “never known [White] to be sober.”

A Facebook page called “Lil Tennessee,” White’s nickname, shows photos of him around Asheville, mostly posted from 2013 to 2015 .

White is described in court papers as kind and easily exploited. He was arrested in Tennessee dozens of times, mostly for public intoxication, records show.

White was once savagely beaten with a hatchet by another homeless person, Morgan told the guardian ad litem in 2020. His girlfriend was killed in the attack. White required more than 200 stitches to his head and had to have his ear reattached, the guardian’s report said.

Morgan told the guardian that her brother once said to her “he intended to drink himself to death so that he could be with their parents again.”

More than 400 arrests in Buncombe

White moved back and forth between Buncombe County and Tennessee. From 2003 through 2006, he was arrested here more than 200 times, records show. His niece told the Buncombe guardian, according to the court document, that White’s drinking had “eventually turned to controlled substances, and [he] contracted AIDS while living in Knoxville, likely from needle sharing.”

White returned to Tennessee and was indicted on more serious charges in 2008, including sexual battery and criminal exposure to HIV, court records show. According to the Kingsport Times News, police alleged White sexually assaulted a mentally challenged woman in her home. He pleaded guilty to three felonies and a misdemeanor and was sentenced in 2009 to six years in prison, court records show.

Morgan told the Buncombe guardian she did not believe White actually committed the crime.

White was released from prison in 2011, got arrested in Buncombe County in 2012, and returned to prison in Tennessee for violating his parole. He completed his sentence in 2013 and was arrested eight days later in Asheville for trespassing.

In a 2014 video posted on outreach ministry Haywood Street’s YouTube page, White described his life on the streets of Asheville and plans to enter rehab. “I’ve found joy in my life now,” he said.

But White continued to be arrested in Buncombe, so often that on at least 99 occasions, he was released from jail and re-arrested in less than 24 hours.

The cycle ended in 2020 after a Buncombe adult protective services worker filed a court petition to declare White incompetent and assign him a guardian. He had been admitted to Copestone, a behavioral health hospital, and to Mission Hospital in the previous month. By then, White had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder, chronic alcoholism, traumatic brain injuries, and seizure disorder “aggravated by (if not caused by) his alcoholism,” court records state.

Asheville Watchdog found White in a nursing home in Hendersonville, where he acknowledged being arrested more than 500 times, before an administrator terminated the interview.

Hope for a Future, an Asheville-based corporation that provides guardianship services, is White’s guardian. Executive director Athena Kinch said she could not comment specifically on White’s circumstances but that the agency represents several people who are arrested frequently in Asheville.

“Some folks, I think we’ve been able to develop relationships with them, get something that clicks with them, find them somewhere to live, and they might still be bumping around some, but things are better, they’re not really going to jail,” she said.

“Then sometimes we have folks where it takes a long time,” Kinch said. “They’re out there using substances, so then they’re erratic in the community, maybe walking in traffic or something, or commit a small crime, and go back in.”

Police have few options

The revolving door of criminal justice starts on the streets of Asheville. The behavior that often leads to the arrests — drinking in public, entering or refusing to leave businesses that have banned them, and yelling profanities — might seem harmless or more a symptom of a mental or substance abuse disorder, but it is nonetheless illegal.

The city of Asheville has ordinances banning panhandling. There are state laws prohibiting trespassing on properties after a person has been asked to leave, or when “no trespassing” signs are present. It’s against the law to be intoxicated and disruptive in public, defined as blocking traffic, sidewalks or entranceways; shoving or challenging others to a fight; or cursing or shouting.

When police observe or respond to a call about those behaviors, they generally have two options: issue a citation, similar to a ticket requiring a court appearance, or make an arrest, Asheville Police Capt. Mike Lamb said.

Another option, if the person is in need of psychiatric or medical care, is Mission Hospital, but “if there’s not an off-duty deputy that is on site at Mission, that process can tie us up for hours,” Lamb said. “I think having more options, having a 24-hour crisis center, would be helpful for not only us but also the community paramedics.”

An arrest can also be initiated by a citizen complaint to a magistrate, who finds sufficient evidence of a crime and issues a warrant.

A frustrating ‘hamster wheel’

Once a person is arrested and taken to jail, a magistrate — an independent judicial officer of the court — sets bonds that determine conditions of release. Options range from a written promise to appear in court, to bonds that are secured, requiring money or a pledge of something of value, or unsecured, requiring payment only if the defendant fails to show up for a hearing.

Magistrates have discretion in determining bonds but generally consider the severity of the crime, a person’s history and their likelihood of returning to court. At a court appearance, a judge can change or reduce bonds and impose conditions, such as allowing release if the defendant agrees to participate in services.

Chief Magistrate Danny Cowan declined to be interviewed about how bonds are set, and his boss, Chief District Court Judge Calvin Hill, did not respond to Asheville Watchdog’s requests for comment.

Bond decisions are an important and controversial part of the justice system. In Buncombe, the public and legal community have complained of bonds being too low for certain people accused of violent crimes and too high for some poor defendants charged with nonviolent offenses who remain in jail because they can’t post bail.

The bond types and amounts for all of the people frequently arrested are not readily available. North Carolina and Buncombe courts do not maintain bond information on specific cases electronically. The jail booking database contains only the most recent bond entered and lacks the capability to track bonds set by magistrates and changes ordered by judges, county data analyst Lee Crayton said.

Paper court files are the only complete record of bonds in Buncombe and many files older than 2018 no longer exist.

Asheville Watchdog manually reviewed nearly 50 court files on the people with the most arrests and found magistrates typically set secured bonds of $100 to $1,000.

In more than a dozen cases, the secured bonds appeared to be intended to hold the defendants overnight or for several hours until they sobered up. “Hold bond hearing when sober and cooperative,” several of the bond forms said.

At bond hearings, typically the day after arrest, judges in eight of the cases changed the bonds to unsecured, allowing for the defendants’ release while also imposing conditions such as participating in treatment or services.

When the repeat offenders examined by Asheville Watchdog were arrested on more serious crimes, their bonds were higher, as much as $60,000 secured, and they remained in jail longer, sometimes a year or more.

More than two-thirds of their crimes were Class 3 misdemeanors, each punishable by no more than 20 days in jail.

“We used to more frequently plead people to time served the next day almost,” Casterline said. “They’d get booked at night. They bring them over [to court] in the morning, say you have a right to have a lawyer, and the person went, ‘Oh, well, can I just plead guilty for time served?’

“Some judges might say, ‘I’ll give you a couple more days,’ ” Casterline said.

A 2019 law expanded rights of victims to be kept informed about a case and has been applied in Buncombe to charges including trespassing, Casterline said. “That kind of slows us down in getting them out of jail a little bit,” he said.

Still, the maximum punishment for these low-level misdemeanors is 20 days, even for those with multiple prior convictions, whether they have 5 or 100. For people with three or fewer prior convictions, the punishment is a fine and no jail time.

“Are we going to fine people with mental health and substance abuse issues or housing issues into a better place?” said Buncombe County District Attorney Todd Williams. “ I think the answer is clearly, ‘No.’ ”

Even if a defendant accumulates multiple charges, all Class 3 misdemeanors, the maximum punishment is still 20 days in jail under North Carolina law.

“Judges don’t have a great amount of discretion,” Williams said.

The result: The repeat offenders are often released from jail after a few hours or a few days.

“Folks see the arrest happen, and then they see the offender right back out down where they were and they’re left with the impression that it’s the District Attorney’s office that’s doing that, when in fact the DA’s office has absolutely zero to do with [it],” Williams said.

But, he acknowledged, “The hamster wheel is extremely frustrating to people.”

Kathy LaMotte, an assistant public defender, said people see the pattern and say, “ ‘Well, the problem is we’re letting them out.’”

But, she said, “No, the problem is, this is not the right hammer. This is not the right implement to deal with this problem.”

Many of the repeat offenders are unhoused and have nowhere to go when they get out of jail, especially if they’re released at night after the homeless shelters close, Casterline said.

“Eventually they’ll get arrested for trespassing, and if they’re drunk, they’ll argue,” he said. “A lot of them, it’s mental health problems.”

Homeless services agencies try to line up housing. The county contracts with the nonprofit RHA Health Services to provide behavioral health services in the jail, “trying to get these people engaged with services, to get them out of this cycle and develop a plan for them,” Casterline said. “Sometimes that works, or sometimes it works for a while.”

“Providing services to people who have severe persistent mental illness is a real challenge,” Casterline said. “They don’t make appointments. They’re not sitting there thinking, ‘I need to change and get my life together.’ . . . Even on their best day, they’re gonna have a hard time, they’re gonna be getting in trouble.”

One man’s journey

Shay Fox, the second-most-arrested person in Buncombe County since 2010, has a long history of mental illness.

He has been charged with threatening and assaulting people, tossing his girlfriend’s TV out a window, yelling and cursing in public, refusing to leave downtown businesses, and returning to establishments he has been banned from, including shelters for the homeless, court records show.

“(T)the defendant named above unlawfully and willfully did, without authorization remain on premises of the Salvation Army,” one arrest record states, “after having been notified not to enter or remain there.”

Records from another arrest state Fox had an open 40-ounce bottle of Hurricane malt liquor and a machete at an undisclosed location. He was arrested for resisting arrest at Pritchard Park, and in Pack Square for having an open bottle of alcohol and shouting obscenities, the records say.

After arrests in 2015 for assault on a government official, trespassing, and intoxicated and disruptive behavior, court records show, Fox was found incapable to proceed to trial and was involuntarily committed to Broughton Hospital, a state psychiatric center in Morganton. He’d already had 26 arrests in Buncombe County in the first seven months of that year, according to booking data.

“He has a history of long standing untreated psychosis,” a Broughton psychiatrist wrote in a 2016 court affidavit. “He is homeless and was living on the streets of Asheville. He carries the diagnosis of schizophrenia continuous, other specified personality disorder with antisocial traits, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder and stimulant use disorder, cocaine.”

“While he is compliant with medications in the hospital he does not think he needs medications and he has no intention to take his medications upon discharge,” the psychiatrist wrote.

A guardian ad litem wrote in a 2016 court report that Fox had worked as an electrician’s assistant and that he contended “a lot of his problems stem from being homeless and trying to solicit enough money on the street to live on. . . He believes he is continually arrested because the police want him off the streets.”

Fox was discharged from Broughton and by 2018 had returned to Asheville, and his arrests resumed. In 2021, at Fox’s request, a Buncombe assistant court clerk restored his competency, allowing him to manage his own affairs.

But in March this year, Fox was found incompetent to proceed on new charges, including felony assault, intoxicated and disruptive, trespassing and resisting arrest. District Court Judge Patricia Young ordered Fox sent back to Broughton or a similar facility and then returned to Buncombe to face his charges.

He has been in the Buncombe Detention Center since October on a $30,000 secured bond, according to the jail inmate website.

Asheville Watchdog attempted to contact Fox in jail and left messages for his public defenders. None of them responded.

A better way

This pattern is not unique. Cities nationwide repeatedly lock up people with disruptive behavior fueled by mental illness, addictions, and a lack of housing, a response shown by research to be costly and often ineffective.

“Communities across the country have recognized that a relatively small number of people cycle repeatedly through local jails, hospital emergency rooms, shelters, and other public systems,” according to “Data Driven Justice: A Playbook for Developing a System of Diversion for Frequent Utilizers,” a 2021 report by Arnold Ventures and the National Association of Counties.

“Their conditions often worsen if arrested and incarcerated, leading to costly recurring interactions with emergency medical services, law enforcement, and other services. Despite the many resources devoted to responding to frequent utilizers, care is often provided in fragmented ways that do not promote recovery or better outcomes for individuals or communities.”

According to data cited in the “Playbook,” a quarter of people entering U.S. jails are accused of misdemeanor crimes; 44% who are sentenced to jail have been diagnosed with a mental illness; 63% have a substance use disorder; and 45% have chronic health problems.

“Recidivism is fueled by mental health and substance use,” Buncombe District Court Judge Julie Kepple said. “Recidivism, poverty, mental health, substance use, and housing are historically a constant in the legal system.”

Reducing “this population’s contact with the courts,” the judge said, requires an effort locally and nationally on “prevention, response, and treatment for mental health and substance use.”

A key to breaking the arrest cycle, according to the Playbook, is sharing data on the frequently arrested between agencies, including the jail, emergency services, and mental health providers, to better coordinate care and prevent the crises that often lead to more arrests.

Buncombe County and Asheville currently don’t do that.

Some of the homeless service agencies do not even enter data about the people they serve into a federal database, the Homeless Management Information System.

“We are lacking in good data in our community. Full stop,” said Emily Ball, Asheville’s homeless strategy manager. “We have a lot of work to do to get to a high-functioning HMIS and then, sort of different but related, work to figure out how we can marry that with other large data systems systems like health care or behavioral health or criminal justice.”

Buncombe County has a jail diversion program with the goal of protecting “public safety while diverting people from courts and jails as appropriate to treatment and services in the community.” The county contracts with RHA Health Services for diversion, including a “Familiar Faces” program, at a cost of up to $86,000 for the 2023 fiscal year.

Familiar Faces targets people who have been arrested five or more times within six months, said county spokeswoman Kassi Day. It started more than six years ago, she said.

Buncombe County Justice Services Director Tiffany Iheanacho said “the staff of different agencies meet periodically to discuss those individuals and how to better serve them, if it’s giving them access to housing or engaging mental health services.”

RHA Health Services did not make anyone with Familiar Faces available for an interview, despite repeated requests from Asheville Watchdog.

The Watchdog requested results of Familiar Faces. The county provided data for one year, showing arrests for 17 people in the program declined 45% from 2019 to 2020.

The booking data analyzed by Asheville Watchdog — for the 55 people with 50 or more arrests — shows that total arrests for that group peaked in 2013 and began declining by 2018. A number of factors contributed to the decline in addition to diversion, including a concerted effort to keep low-level offenders out of jail during the pandemic and a loss of police officers that resulted in Asheville Police no longer responding to minor crimes.

A number of the repeat offenders also appear to no longer be on the streets of Asheville.

At least nine have died, including five from drugs or alcohol and two of whom were struck by cars as pedestrians and killed, according to death certificates. Another is in prison. The No. 1 offender, White, has been in a nursing home, and the No. 2, Fox, has been in jail.

One of the recommendations of a consultant hired to guide Asheville’s approach to homelessness, presented in January, was to create a “housing focused pilot program for 10-20 high utilizers of multiple systems of care — eg., emergency room, jails, shelter,” according to the report by the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

Housing reduces arrests

Another potential solution is “permanent supportive housing” — affordable housing with social workers readily available to line up health care, treatment and employment.

Homeward Bound has provided such housing at 15 Woodfin St. since 2015. Owned by the Asheville Housing Authority, the 18-unit building is designed for “individuals who really have no other opportunity in Asheville for housing,” said Alanna Kinsella, Homeward Bound permanent supportive housing assistant director.

A 2019 study of 14 residents’ arrest records found that the group had a combined 121 arrests in the year before they moved into the apartments and just 42 in the year after, a reduction of 65%.

Kenneth White was an exception.

He moved into one of the apartments in 2015, according to a court document, and was arrested even more in subsequent years. White had assistance, including a case manager, food from Meals on Wheels, $80 a week in spending money, and reminders to take his medications, court records state.

But he had deteriorated by 2020, the records state, and a social worker described his apartment as being “in disarray.”

“The floor was covered with garbage, mostly food containers and empty beer cans,” according to a court document describing the visit. “There was dirty clothes and [linens] on the floor. The apartment had an odor of stale beer, urine and feces. The apartment is infested with bedbugs.”

Housing Authority Executive Director David Nash said he remembered White and his situation and called it “an extreme outlier.”

Despite White’s experience, Casterline said he’s seen the arrest cycle stop or slow significantly for many people when they move from the streets to an apartment. “You’ll see that the arrests go way down once they have housing,” he said.

Kinsella agreed.

“Once we get people into housing, we see them really come out of that [cycle],” she said. “Those charges, we call them homeless crimes.”

“Having a home, having a house, I’m not going to be charged when I drink a beer in my backyard,” she said. When “somebody’s having a bad day and the only thing they want is a beer and the only place they have to drink it is on a sidewalk, they’re getting a charge.”

LaMotte, the assistant public defender, also believes housing is the solution.

“I think if we as a society could somehow provide a little more structured housing, I think that is going to be a huge part of it for a lot of these folks,” she said. “For a while when COVID hit we were putting a lot of homeless people into a hotel … and people were not committing the crimes.”

Two former hotels are being converted into supportive housing for nearly 200 chronically homeless people, one by Homeward Bound scheduled to open this year. The other, by the city of Asheville, had been scheduled to open in 2023 but now won’t be finished until March 2024, according to the project’s website.

“I would think that will make a very significant difference,” Casterline said.

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and surrounding communities. Andrew R. Jones is a Watchdog investigative reporter. Email arjones@avlwatchdog.org. Sally Kestin is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter. Email skestin@avlwatchdog.org. John Maines was part of teams that won two Pulitzer Prizes for Public Service, in 2013 and 2019. Email: jmaines@avlwatchdog.org

For a very in-depth article, they sort of buried one of the most important stories, which is the existence of Familiar Faces and a suite of other diversion programming, whose inception largely coincides with the decline in high-volume rearrests.