ASHEVILLE — When Fran Schlesinger’s scholarship money ran out, she turned to the Army’s student nurse program to complete her education — but she didn’t tell her fellow students about it. “It was at the time of Kent State and the Vietnam War, so you didn’t publicize you were going into the military,” she explains. “There were three of us in our class that joined the Army, and we didn’t let people know, just because of all the demonstrations.”

Schlesinger, the oldest of 11 siblings, says her father was adamant about her getting a college education, but she needed financial help. And though the Army program was available, there was another complication. “At that time, it was interesting, women had to be 21 without parental consent, and men were 18,” she recalls. “My father said, ‘I will not sign for you if you volunteer for Vietnam.’ We had just had our neighbor killed in Vietnam, so I had to promise him that I would not volunteer.” If she were stationed there after she graduated, he told her, he’d be OK with it.

That didn’t happen, however. By that time, says Schlesinger, they were sending only experienced intensive care unit and emergency room nurses to the war zone. But when Schlesinger realized she had a knack for the fast-paced work environment, the two years of service she owed the Army in exchange for the financial support turned into 22.

Schlesinger retired in 1993, and these days she volunteers with the local chaper of the American Red Cross, serving as a disaster action team leader and teaching CPR classes. She recently played a vital role in helping the more than two dozen Aston Park Tower residents who were displaced by an Oct. 17 fire, says Jerri Jameson, the nonprofit’s regional communications officer.

“She was there at the apartment fire itself,” Jameson explains. “She was dealing with a very vulnerable population, some that needed some medical assurance, if nothing else.” After that, continues Jameson, Schlesinger helped set up emergency shelter at the Stephens-Lee Recreation Center, working through the night without sleep. The fire, says Jameson, “hit the community hard, even our Red Cross community. It was local. Then to see people like Fran jump into action like that, it was amazing.”

For her part, Schlesinger says only, “I had a good team!”

Trials and triumphs

Schlesinger says her transition to civilian life was fairly smooth. She was a full-time mom with her family in Vermont, a place she describes as very welcoming to veterans. But her husband, who’d also served in the military, had a hard time finding employment due to his specialized skill set — a not uncommon problem, says Schlesinger.

And for Alyce Knaflich, the struggle wasn’t so much finding work as it was holding onto the jobs she found. After more than 19 years in the Army and Army Reserve, Knaflich left the military with an honorable discharge and received a lump-sum separation benefit. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Virginia Tech and moved to Iowa but soon found herself dealing with previously untreated post-traumatic stress disorder. “I finally couldn’t take it no more, had a breakdown and went to the VA Hospital,” she explains.

Despite her diagnosis, says Knaflich, she didn’t receive disability compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs; under federal law, the department must withhold any further payments until the separation benefit has been repaid. As a result, Knaflich wound up being homeless for many years, traveling around as she tried to find employment and housing. AMVETS finally helped Knaflich get back on her feet, and by 2009 she was ready to start helping other women veterans.

That included cooking meals at the Asheville Buncombe Community Christian Ministry’s Steadfast House, a shelter for homeless women and their children. But Knaflich says women weren’t being given the same job training opportunities as men, citing a sex-discrimination complaint filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2012 that was settled in October 2016. ABCCM agreed to revise its programs and policies to ensure equal access and to provide staff with anti-discrimination training.

In 2014, Knaflich founded the Aura Home for Women Veterans. The nonprofit has an office in the United Way Building in downtown Asheville and is currently taking donations to help renovate a property the organization owns in Hendersonville. Besides providing long-term, supportive housing for homeless female veterans, Aura aims to raise awareness about the difficulties these veterans often face, including limited job training opportunities, PTSD and military sexual trauma.

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, about 1 in 5 women screened by the Veterans Health Administration say they’ve experienced some form of MST. But Knaflich, an MST survivor herself, believes the real number is much higher. “The sad thing about it is that women are so fearful about reporting it,” she says. “It’s usually their supervisor, someone in their command, and they know it’s not going to go anywhere so they keep their mouths shut just to survive.”

Knaflich hopes to combat this by shining a spotlight on the problem, and although Aura just celebrated its third birthday, “The work’s not done yet,” she remarks. “Even today, with the VA Hospital and these bunch of service organizations, women veterans are not welcome. That’s why, when you go to meetings, you may see one or two. Buncombe County has over 2,000 women veterans. Where are they?”

Falling through the cracks

Women account for about 11 percent of Buncombe County’s more than 18,000 veterans, according to population data from the National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. But their participation in local veterans programs falls far below even that modest number.

Stephanie Franklin, director of transition and parent programs at UNC Asheville, serves as the adviser for the University Veterans Alliance, a student group. Since its inception in 2012, she says, very few female veterans have been involved with the group; there are currently two active female members and four males. “Previously, I’ve always had maybe just one female and then the rest were all males,” she explains. “So it’s been great to have more of a presence.” Overall participation fluctuates, and because the group is somewhat smaller at the moment, “Having two females come in has really amplified the difference.”

The problem isn’t limited to students. “I think when women come out of the military, it’s difficult to develop what we call a tribe: a book club or a group of women that they can confide in, because they’re very different in their backgrounds than most women,” notes Charlotte-based leadership coach Cindi Basenspiler.

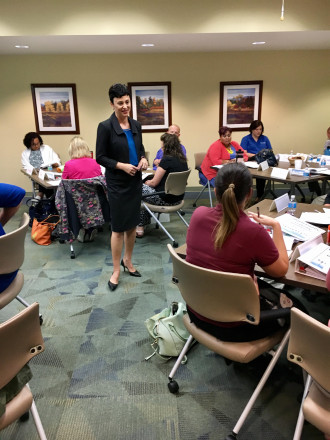

The author of the recently published Opportunity Cost: Owning Your Choices, Basenspiler served three years in the Alabama National Guard as an enlisted soldier and eight and a half as an active duty Army officer. She now offers transition coaching and organizes workshops, such as the Nov. 14 “Women who Serve(d)” event in Charlotte. Sponsored by the Asheville-Mountain Area chapter of the Red Cross, it featured women service members and veterans speaking about their experiences in and out of the military and what steps they’ve taken to achieve workplace success.

“When we first got out of the military, it seemed like the choices were either go to college or get a job,” Basenspiler explains. The workshop was designed to help participants realize that there are other career possibilities. One of the presenters, she says, is an artist, and several own their own businesses. Basenspiler believes focus and hard work are the keys to success.

But while she’s proud of her accomplishments and feels she was mostly respected during her military service, Basenspiler says there were times when someone didn’t take her seriously because she was a woman in a leadership position. Those challenges, however, didn’t outweigh the positive experiences she had. “Very quickly I rose into leadership ranks, so I possibly didn’t have as many issues as some others.”

Too often, she maintains, the media perpetuate the idea that all women service members have negative experiences. “This is why I think women don’t own the fact that they’re veterans, because people conjure up, ‘Oh, bad things happened to you in the military,’ and that’s unfortunate.”

Schlesinger agrees. And speaking up, she says, can make all the difference. Her own advice for those transitioning into civilian life is to actively explore the many existing programs and facilities. “Don’t be afraid to reach out; don’t be afraid to seek out what resources your community has,” she counsels. “If you don’t know where to start, start with the VA: Give them a call, tell them you’re a new veteran or you’re new to the area or you’re just a veteran having problems. They want to reach as many veterans as they can, but they can’t if they don’t know you’re there.”

Thank you for publishing this article. The situation described applies far beyond Buncombe County. It is a national issue that women veterans are ignored, discounted, and erased.

When I left the Army in 1975, the VA doc who did my exit physical told me, “We’ll never see you again because you are a woman.” I don’t see where that has changed much for women veterans of recent conflicts.

Please publish more articles like this one. We served, too.