On Nov. 21, Gov. Pat McCrory’s office released a statement saying that all of the jobs North Carolina lost during the Great Recession — some 62,000 positions — had been gained back.

Not long after, local unemployment numbers started coming in, showing that Asheville had the lowest unemployment numbers among the North Carolina metro areas at 4.1 percent.

What does all that mean? Perhaps not what you might think.

Tom Tveidt, a 20-year veteran of economic research and owner/founder of Syneva Economics, a local research company, has a wealth of experience with the average person’s misunderstanding of the economy.

“I’ll do these presentations,” says Tveidt, “and at the end, someone will say, ‘How come jobs aren’t growing faster here?’ And there’s an entire book to that answer; unfortunately the media, especially the TV media, just make it seem so simple.”

The same holds true for the 62,000 jobs number. A single stat, says Tveidt, cannot come close to telling the whole story: “The recession was so dramatic; it really changed everything. It’s never going to return to what it was.”

“For example,” he says, “construction jobs are still way down, and that’s where a majority of the losses were. Are those going to come back? Probably not; we’re not going to be in that [construction] boom again. You’re not just replacing what was lost: [The market is] all new. Those people who lost their [construction jobs], they’re not going to get them back. They’ve gone off to do something else.”

A component to these misconceptions, he says, is a too-heavy emphasis on the notion of a “state’s” economy.

“This stuff is a local phenomenon. There are 15 metropolitan areas [in North Carolina], and each has its own story. There’s really no ‘state’ economy. It’s an aggregation of the smaller ones.”

And one of the more misleading statistics on a state level? Unemployment figures, which leave out potentially large groups of people.

“It’s an econometric model,” says Heidi Reiber, research director at the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce (whose job Tveidt once held). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates the national unemployment rate based on a household survey, then tailors the information for each state by adding in unemployment insurance claims and other payroll employment measures, Reiber notes.

“Unemployment numbers are very unreliable,” Tveidt says. “They’re an estimate of an estimate [on the state level]. The way they collect them, it’s a phone survey. In Asheville, it’ll be a couple of calls, probably, and they’re going to extrapolate that out.”

“You’re (by definition) unemployed if you’re actively looking for work and you can’t find it,” he says. “If you say, ‘I gave up a long time ago,’ you don’t count.”

Adds Reiber: “People are classified as unemployed if they do not have a job, have actively looked for work in the prior four weeks, and are currently available for work.”

This means people who don’t factor into unemployment percentages include those who haven’t looked for work in 32 days or more, those who are injured and unable to work, even if for short periods of time, and people on a company’s payroll in any capacity, even if working a few hours per week or month.

“The [state] survey is so bad,” Tveidt says, “that it’s not statistically valid.”

Indeed, the Raleigh News & Observer’s “Biz Blog” reported Oct. 24 that a quarterly federal measure of the joblessness rate for North Carolina was almost double the monthly joblessness rate released by the state for September. The so-called U6 rate, released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the U.S. Department of Labor, put North Carolina’s unemployment rate at 12.6 percent, versus the 6.7 percent rate released by the state. The U6 measure includes “underemployed” workers plus people who stop job-hunting because they’re discouraged, according to Biz Blog author John Murawski, who also noted that the U6 is considered “the broadest existing measure of unemployment.”

However, these numbers aren’t broken down into local regions.

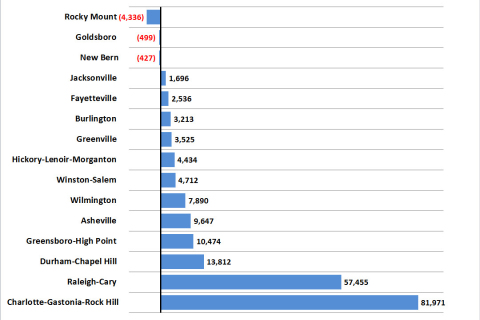

Regaining 62,000 jobs also does not account for specific local impacts. The metro areas seeing the largest job gains since the beginning of 2010, according to the N.C Division of Employment Security, are the Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill area (which includes some parts of South Carolina), and the Raleigh-Cary area (See “Net Job Gains” chart). Other metro areas have had significantly less gains, if they’re gaining at all.

And Asheville? “We’re doing OK here,” Tveidt says.

Market realities

To more fully understand the local employment situation, it helps to see the bigger picture. The three economic indicators for Asheville, notes Tveidt, are health care, tourism and manufacturing.

“The technical term is ‘specialization,’” he says. “So Las Vegas is in entertainment, Silicon Valley’s making chips. We are tourism, manufacturing and health care. If you want to forecast how Asheville’s going to do, you look at those three.”

Health care (officially designated as “health care and social assistance”) is the largest, with 23,760 employees in 2013, according to NCDES.

There is no official designation for tourism, but it’s generally included under the category of “leisure and hospitality,” which itself breaks down into “accommodation and food services,” and “arts, entertainment and recreation” in NCDES data. There were 16,583 such jobs as of 2013 in Asheville.

“Health care’s kind of in a weird place, tourism’s doing really well, and manufacturing, it’s up a little bit, but not huge,” says Tveidt. “We’re kind of relying on the growth that comes out of the tourism and health care side of things right now.”

For decades, employment in the region’s health care sector has grown steadily a few percentage points each year, says Tveidt. Now, however, with the advent of the Affordable Care Act and all it entails, the pace of growth has been disrupted — “and I’m not sure anyone truly knows how that will shake out here,” Tveidt acknowledges.

Manufacturing is smallest of the three, with 10,792 employees as of 2013, and its growth is small. But what manufacturing has that makes it a strong economic indicator — and what the other big industries in Asheville do not have — is a large GDP (gross domestic product).

The trouble with tourism

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis defines GDP as “the measure of the market value of all final goods and services produced within a metropolitan area in a particular period of time (annually).”

Take manufacturing, for example. “When you think of manufacturing — what do they do? They take a bunch of parts, and they put them together and they charge a whole lot of money for that. The value of what they make is really high,” Tveidt explains.

He brings up Asheville’s budding local beer-brewing industry, which is counted as beverage manufacturing. Even with good wages, the craft-beer industries that make up Asheville’s lifeblood simply do not have the GDP to pull wages up and compensate for Asheville’s high cost of living — the highest in the state, in fact. The largest local industry, health care, seems like it would — but its GDP includes health care support occupations, which have a mean hourly wage of $12.77.

“Health care includes nursing care and nursing homes and that sort of stuff,” says Tveidt. “The lower wages are probably on [that side].”

The biggest culprit, however, is tourism.

“Tourism breeds low-wage jobs,” says Vicki Meath, executive director of Just Economics of Western North Carolina, an Asheville nonprofit.

“One of the problems is that many of the industries that fueled Western North Carolina 30, 40 years ago have generally left and have been replaced by tourism,” Meath says.

Tourism is linked to huge swaths of what Asheville is known for: food, hotels and leisure. It also has a symbiotic relationship to retail. “Tourism is directly related to retail sales,” Tveidt says. “People come here, and they buy stuff.”

As it turns out, people bought $1.5 billion worth of stuff in 2012, Reiber says. This also led to an additional $800 million in sales from “direct and induced impacts,” she notes. So all told, tourism and its related industries generated $2.3 billion in sales in 2012, as well as about $250 million in tax revenues.

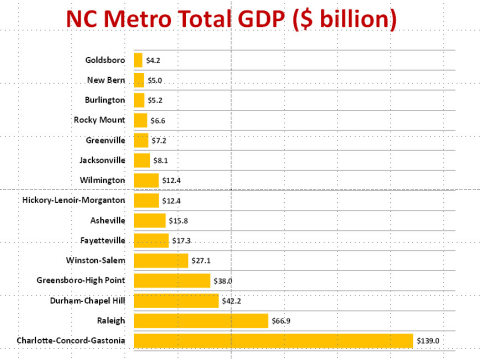

And that’s just a part of it. Asheville’s economy as a whole appears very robust. Its total GDP was some $15.8 billion in 2013, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

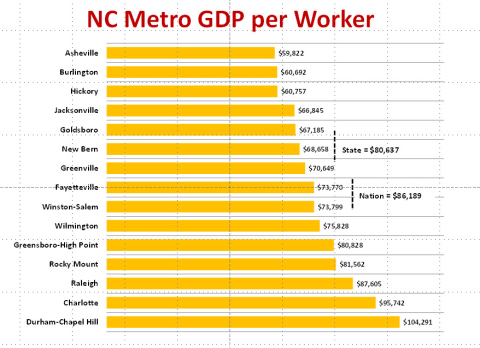

Yet the GDP per employee — representing what each employee contributes in pure economic terms — lands Asheville dead last in North Carolina. Syneva calculates Asheville’s average per-employee GDP at $59,622.

By comparison, Durham-Chapel Hill, ranked No. 1, has a per-employee GDP of $104,291.

While local employees in tourism-based industries actually fare better than their counterparts in other areas of the state, according to NCDES figures from 2014, the wages are so low that it doesn’t approach the actual cost of living. That leaves Asheville employees working long and laborious hours doing jobs that don’t have much pure monetary value simply due to the intrinsic nature of the business, and thus naturally tends to push wages down.

This is not to say that tourism is without merit. Jobs connected to tourism do “contribute to the region’s diverse economy,” says Reiber. “Diverse economies function more effectively and weather downturns better.”

But economic durability can’t negate the low wages influenced by low GDP. And there are also few answers for other factors keeping wages low in tourism jobs, such as the skills and education level required for such positions.

“Many [tourism] jobs are entry-level,” says Tveidt. “That’s not to say they aren’t labor intensive. They are valuable. But they’re not specialized skills.”

Adds Reiber: “While many of the associated occupations [in tourism] pay below the average wage, this can be tied to factors that include … education requirements for workers.”

Living wage issues

Just Economics recognizes the realities of the local economy and tries to effect change within that framework. “Profit margins are lower [in tourism industries],” Meath says. “That’s why we work with businesses that try to help them get to a living wage.”

In particular, food-service wages of all types are notoriously low. The average hourly wage for food preparation and serving-related industries, as classified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is $9.99 per hour. This average includes all types of waiters, cooks and first-line supervisors. It’s the lowest wage in the Asheville area.

Using a complex formula based on federal poverty guidelines, Just Economics calculates the living wage for the region as $11.85 per hour without insurance, and $10.35 an hour with insurance. At just over 200 percent of the federal poverty level, the living wage reflects what someone would have to earn to purchase basic necessities without any government assistance.

“I think some people believe that wages are determined by the person running the company,” says Tveidt. “And obviously there’s some discretion there. But they ask, ‘How come they just don’t pay them more? Are they keeping it all to themselves?’ No, it’s just the composition of our economy. It’s the [economic] value of what they’re making.”

But, says Meath, wages can be increased if a business is determined to reach that goal: “There’s a variety of factors that have helped [area restaurants raise wages]. We’ve had lots of restaurants [start paying living wages], from Rocky’s Hot Chicken Shack to Bouchon. If there’s a commitment … we can work through those things and understand the long-term impacts. It might feel like an investment, but the long-term impacts prove better results.”

Since 2007, Just Economics has certified almost 400 organizations that pay a living wage, starting with Asheville city government employees.

“It’s a process,” says Meath. “But we have some savvy, intelligent business owners in this community, and it’s just a matter of trying to talk with them and walk with them, because they understand their business.”

The results, she says, bear out both locally and in studies. “We have the anecdotal evidence locally and the data nationally that shows workers that are paid a higher wage stay longer, and you save money in recruitment, retention, training and development and productivity. Having someone on the job for two years is more economically beneficial to the employer than having someone who’s been on the job for two weeks.

“You’re looking at these things that are subtleties,” says Meath. “But when you look back at the end of the year, you see those [savings].”

The part-time workforce

Another piece of the local economic puzzle that’s not easily represented in statistics is tourism’s impact on the number of hours each employee works per week.

The average weekly wage for a person working in the category of accommodation and food industries was $314 in 2013, according to NCDES. Meanwhile, retail workers averaged $453 per week that same year. What drags this average so low is not just the wages themselves, but the few hours many employees get.

“[Asheville] always comes out really low on average weekly wage because we have such a strong tourism industry,” says Tveidt. “And a good portion of that — we can’t be sure how much exactly — but a good portion are part-timers.”

At $10.35 per hour (the Asheville living wage with insurance), someone working 40 hours a week would earn an annual wage of $21,528. At $11.85 per hour (the living wage without insurance), someone working 40 hours a week would earn an annual wage of $24,648 per year.

Yet the average weekly wage for someone in food services ($314) yields only $16,328 annually for a 40-hour week. For retail, the average weekly wage translates into an annual wage of $23,556 for a 40-hour week. And with fewer hours, part-time workers are taking home even less.

These two industries accounted for 30,000 people in Asheville’s workforce, just a shade over 25 percent.

Once more, says Tveidt, “put [these industries] up against something like manufacturing. Their employees are going to work 40-50 hours a week.”

“There’s multiple facets to [the part-time wages],” says Meath. “We need support systems that allow people to be able to work. Child care’s a huge barrier for low-income families. Having a more efficient transit system … would expand the amount of time people are available to work. And I think that raising wages in general helps. Imagine if someone is working 30 hours a week at two minimum-wage jobs. So you’re working 60 hours. Now let’s say you make $15 an hour. Now you can work one job for 30 hours and still maintain your lifestyle. You’ve just freed up this other job for someone else to do.”

Possible change

If Asheville finds success in creating a widespread living wage, says Meath, it will be because of the strong local business community: “The success we’ve had is not with corporations, but with businesses invested in the community. When you live here, and you know the cost of housing is really inconsistent with wages, and you want this community to thrive, you understand living wages differently than if you’re a shareholder in Iowa or wherever.”

But, Meath says: “It’s harder for a small business unless everyone’s doing it.”

And, says Reiber, “organizations face a variety of challenges … while one organization might be able to increase wages, another may not, or it may find it has to compensate in other ways to remain competitive.”

Indeed, one of the biggest pushbacks about raising wages is the prospect that a business might have to cut positions because they cannot afford to pay all employees the higher wage — not to mention the fear of financial losses.

But, says Meath, while employers do sometimes suffer slight initial losses, “every time that happens there’s been a bounce-back. The economy makes up for it. We have employers saying, ‘Yeah, this cost me more money initially, but then I was able to recoup that.’”

The number of jobs, she says, increases as well: “When low- and middle-income people have money in their pockets, it’s circulating in the local economy. Now all of the sudden, you can go to the local pizza shop instead of eating ramen. When that pizza shop has more customers, the owner needs more employees. We see, in that sense, that raising wages is an economic benefit … workers are consumers. When … we have more consumers, our economy is more sustainable.”

Notes Reiber: “Additional household income provides workers the opportunity to purchase basic needs and beyond, and purchases may serve to boost the economy. As long as a higher wage doesn’t threaten the organization’s ability to sustain itself or compete effectively.”

“We don’t want businesses to make decisions that put them out of business,” Meath says. “That’s certainly not good for the workers — so we’re certainly not in this to say, ‘Do something that’s going to harm your business.’”

So what is Just Economics’ hope for businesses? “Coming to an understanding of what a living wage is, how it’s good for a business and how it’s good for the community. We see the sustainability of living wages; let’s try to walk with you and see if there are any connections we can make in order to help you get there.”

And Meath has some statistics of her own that bear noting: “Half of our kids in public schools in this county are living in families that can’t meet basic needs without public or private assistance, or solutions … like unsafe or doubled-up housing,” says Meath. “When we look at it from that perspective, is $11.85 really that much? Don’t all workers that are working full-time, 52 weeks a year deserve to put a roof over their heads and bread on the table?”

That’s a point also made by Patrick McHugh in a Dec. 24 “Progressive Pulse” post for NC Policy Watch, an independent project of the NC Justice Center (a nonprofit anti-poverty organization): “One of the most distressing aspects of the last few years is how many of the middle-class positions lost during the recession were replaced with low-wage employment, part-time work and jobs with few opportunities for career advancement.”

Noting that the economic recovery has done nothing so far to reduce poverty in the state, he concludes, “If we don’t honestly look at what policy changes are needed to ensure that hard work pays, the economic damage of the recession will become a permanent reality for many North Carolinians.”

And nobody wants those kind of statistics.

Eisenhower (surprisingly enough) talked about the need for balance between the public and private economies in his farewell address. There is congressional legislation collecting dust that would bring additional billions to WNC and bring us on par with top civilizations like Denmark. Including the Climate Protection Act that includes a cash dividend to citizens from a Federal carbon tax.

Several years ago I wrote about the fact former congressman Charles Taylor’s ‘bring home the bacon’ mystique was just that,,, myth. These links show WNC Federal expenditures are at the bottom… as of 2003. Has there been any update as to what WNC Federal expenditures are in comparison with the rest of the nation as of 2014?

Let’s start working with top level executive data about our communities here in the USA. That’s the first step to ethical strategy. Tveidt and Rieber aren’t the only civilization thinkers in the area, but good article just the same, Cameron. I think C-T is using quotes from Just Economics now, but not enough from the NC Justice Center.

http://trac.syr.edu/tracreports/fedfund/112/

http://trac.syr.edu/tracreports/fedfund/112/include/table_1.html

Asheville has the lowest unemployment rate? Hooray. This area was always the place where jobs were hard to come by. Having lived there for a large portion of my life, I can tell you they have the best entertainment, best farmer’s market, best doctors, best people to know, best music, prettiest view, and best churches. It is a different atmosphere . But please just visit and don’t stay because I don’t want it ruined.

The University of North Carolina is located there and provides wonderful opportunities for young and old. The Biltmore House is beautiful and has several restuarants.

Henry Ford got it right when he raised the wages of his employee’s so that they could afford to buy his cars. Trickle down economics has proven over and over again that it doesn’t work. Isn’t it about time that we reverse the flow.

Of course we have low unemployment, everyone needs at least two jobs to live here.

Tell it brother!

Appreciate your deep insight on real labor metrics and their many roots.

I’m sure you’re a aware of oft overlooked output impact economic drivers generated by a 30 year sustained investment in Tourism by state and local sources. (See attached charts.)

Key is the annual conversion of about 310,000 “Turbo-Tourists” to permanent residents, from the estimated 6-7% set of the annual 53 million NC visitor flow, made up of people with relo, second home, retirement motivations. Our 26-question, Carolina Lifestyle Survey™ documents that 12% of these relocating affluent/highly educated folks “say” they intend to start/move a business.

Hopefully the real estate economy will get somewhere up against the previous prosperity…less all the retail speculators this time. The Billions $$$ land buying spree across NC by national builders and private equity outfits is a clear indication of confidence in the long term continued growth of In-migration of affluent, educated families. Every new roof top in NC creates 1.9 new jobs in the region plus, permanent taxable assets.

Confident our Research Briefing on Tourism ($25 B) and it’s linkage as the economic “birth-mother” of the robust, In-migration Industry ($26 B) will be interesting to some of your clients. Be a pleasure to collaborate.

Intentions for Global Peace & Prosperity!

Patrick Mason, Co-founder

Center For Carolina Living & CarolinaLiving.com

4201 Blossom Street, Columbia, SC 29205

Headquarters: 803-782-7466 Cell: 803-467-9570

Pmason@CarolinaLiving.com • @carolinalivingP

I like the article. Now I would like to know why is the cost of living so high here in AVL? Our cost of living is 7% higher than the state wide average and 4% higher than the national average. Except for transportation (at 99 with national being 100) we are consistently high in all other categories: COL index, 104; goods and services, 104; groceries, 101; health care, 108; housing, 103 (they low balled that one!); transportation, 99; utilities, 115.

I believe resolving this would probably be more beneficial to all than raising wages.