On the morning of Aug. 1, employees of the Asheville City Schools’ central office gathered in the boardroom for some back-to-school training. It was the first such exercise conducted on this scale since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, says April Dockery, the system’s executive director of operations.

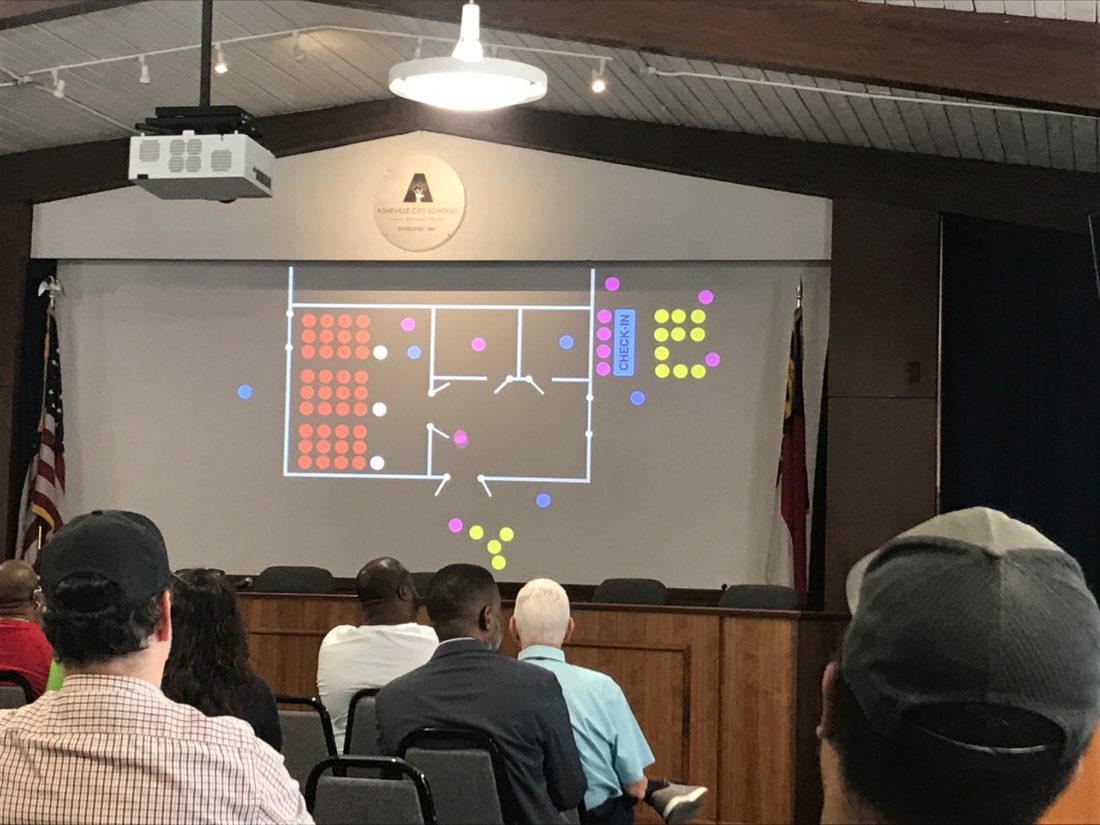

The subject was one that nobody wants to even think about, but everybody knows must be addressed: how to reunify families in the aftermath of an incident such as a shooting. School safety coordinator Jennifer Auner showed a video from the “I Love U Guys” Foundation about how to establish parental check-ins and organize pickup in such situations. She also fielded questions on how this would be implemented in Asheville.

For both the Asheville and Buncombe County systems, another school year begins Monday, Aug. 29. And while every such cycle brings with it jitters about tests and homework, this year carries an additional burden: For many families and system staff, the nation’s continual threat of school violence has become impossible to ignore.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, during the 2020-21 school year there were 93 incidents at public and private elementary and secondary schools in the U.S. in which a gun was brandished or fired. So far this year, Education Week magazine has tracked 27 school shootings as of Aug. 1 — most recently, the May 24 attack at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

The deadliest school shooting in a decade, it underscored persistent questions about school safety, stricter gun laws and ways to “harden” schools to help keep students and staff safe. In Asheville and Buncombe County, those topics are very much on the minds of families, law enforcement and school personnel.

Confiscated weapons

Happily, neither local system has had any on-campus shootings in the last five years. During that period, however, the Police Department has recovered 16 weapons prohibited by the Asheville City Schools, spokesperson Bill Davis tells Xpress. Most were either knives or box cutters; the only gun was a BB gun.

In the same period, the Sheriff’s Office responded to six incidents in the Buncombe County Schools involving weapons, including guns, according to public information officer Aaron Sarver. As in the city schools, those incidents mostly involved things like knives or scissors, though one student did bring a firearm last year.

Students in such cases are typically referred to the N.C. Department of Public Safety’s Division of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Davis explains, adding, “There’s not usually a criminal element — somebody just didn’t stop and think.”

On-site law enforcement

Both local districts employ full-time school resource officers — sheriff’s deputies in the county schools and APD officers in the city system.

This fall, the county system will have 28 such officers, says spokesperson Stacia Harris — one each at all middle and high schools plus shared officers at the elementary and intermediate schools. They’re trained to deal with active shooter situations and serve as liaisons with the Sheriff’s Office, Sarver explains. Their salaries are partly paid by N.C. Department of Public Instruction grants.

The city schools currently have three resource officers: one each at Asheville High and Asheville Middle School, and one shared by the elementary schools, says Davis. There are also some open positions.

Security upgrades

In 2019, the two systems jointly hired a consultant to assess the security at each campus and recommend needed changes. The city system operates nine schools; the county has 44.

For security reasons, Harris explains, “We are unable to go into great detail about these upgrades. … Based on the results of that study, we have implemented security-related professional development courses for all staff.” In addition, several construction projects are underway.

All county schools, notes Harris, use the LobbyGuard visitor management system. And last year, the district upgraded the main entrance of each school so front office staff can “buzz in only the appropriate students, staff or visitors.” The public safety radio network has been upgraded, and an integrated video system “allows the Buncombe County Sheriff’s Office to monitor our security cameras in real time in the event of an emergency.”

This system, says Sarver, is also being tied into 911 dispatch capabilities. Deputies can activate their phones and stream video from inside the schools in real time. “We can see [responding officers’] point-of-view perspective in addition to the fixed cameras,” Sarver explains, adding that the technology will eventually be integrated into body cameras as well.

Harris says all doors are secured with locks that require a key or badge to open; doors that lack outside hardware are exit-only. “We’ve also focused on educating our students not to allow visitors in when they knock on an exterior door,” she says.

The city schools, says Dockery, are exploring giving the APD full access to school cameras. School resource officers can access them at all times and can give the police access in an emergency. The system also uses the Fusus platform to monitor the external portions of schools, and the APD can access Fusus livestreams in an emergency.

Drills, drills and more drills

Local schools conduct drills for multiple scenarios, some involving potential violence.

State law mandates two practice drills per year in every school. One is a run-through for key personnel involved in the planning process. The other is a schoolwide lockdown, which can be imposed in response to either an on-campus incident or a potential threat in the community, such as an unrelated shooting nearby.

In keeping with safety protocols at both the Asheville and Buncombe County systems, local law enforcement and emergency services agencies have created a risk management plan for each school.

Superintendents must provide law enforcement with a key to the main entrance of every school building or emergency access to the devices where keys are stored. If the locks or key storage devices are changed, the superintendents must provide updated access.

The county system also requires all principals to conduct drills for each of the following scenarios: securing the campus perimeter, a tornado, a fire and a bomb threat. The city schools mandate a practice fire drill for students and two bomb threat drills for staff.

Assessing threats

The Sheriff’s Office has one detective dedicated to investigating threats in the Buncombe County Schools; this person works with the school resource officer at each site. Those investigations are expanded if the detective considers the threat to be credible, says Sarver.

Any social media post or tip requiring further investigation is subject to a community threat assessment. In 2018, the Sheriff’s Office conducted eight such assessments; the following year, there were 22. In 2020 and 2021, there were 18 and 23 assessments, respectively, in connection with the county schools. So far this year, 32 have already been completed, and the fall session hasn’t even started yet.

One of the criteria detectives look for is a pattern of behavior indicating the potential for violence, Sarver explains. If an investigation has determined there’s a risk and the detective finds probable cause, they will visit the home, ascertain access to weapons and speak with parents or guardians, as well as the student.

Online chatter

One way threats are assessed is through monitoring communications. The county schools monitor student emails, as well as Google Drive and OneDrive, “for concerning language and keywords,” Harris explains.

In addition, the county system uses a communications platform called SchoolMessenger. The company’s SafeMail product flags messages, which are then reviewed by its Human Monitoring System, a team of experts trained to evaluate such content and alert school systems to “issues like suicide, sexuality, violence, interpersonal conflict and more,” according to its website.

The city schools, says Dockery, monitor students’ Gmail accounts using a program provided by a company called Gaggle.

Along with the schools’ monitoring online communications, law enforcement agencies must also contend with hoaxes. Most hoaxes originate on social media and aren’t generated locally, Sarver tells Xpress. “We often see hoaxes circulating on the anniversary of school shootings,” he notes. Under state law, communicating a threat of mass violence on educational property is a felony.

Usually, he continues, the Sheriff’s Office can determine that a warning of violence is “not a valid threat. But it often sets the rumor mill in motion, and we understand that parents are focused on the safety of their children above all else — and rightfully so.” Accordingly, Sarver explains, “A big part of our work is to assure parents … that we have investigated and that they do not need to be concerned in this instance.”

WHY do we fund TWO separate government school systems? How stupid is that ? How RACIST is that ?