Dan Gurley has heard it all before. As a member of the nonprofit Western North Carolina Rail Committee, he’s quite familiar with the long-running effort to restore passenger train service to the Asheville area. He’s equally familiar with the cynicism many residents have expressed about that effort.

Regularly scheduled service to Asheville ended in 1975; since at least 1995, advocates have been pushing to bring back the trains. After nearly three decades of work and multiple studies by state officials, the most concrete local progress was the 2005 purchase of a potential station site in Biltmore Village by the N.C. Department of Transportation and city government. The 81 Thompson St. property currently provides office, storage and maintenance facilities for Asheville’s Parks & Recreation Department.

“One of the refrains that we hear, unfortunately, is that it’s the same story every time: Western North Carolina gets left out. It’s a damn joke,” says Gurley. (Mountain Xpress shares the blame. Among the “Top 10 Complaints of Asheville’s Gentry” listed in the paper’s 2020 humor issue was this: “Delay at station for next train to Raleigh now approaching 50 years.”)

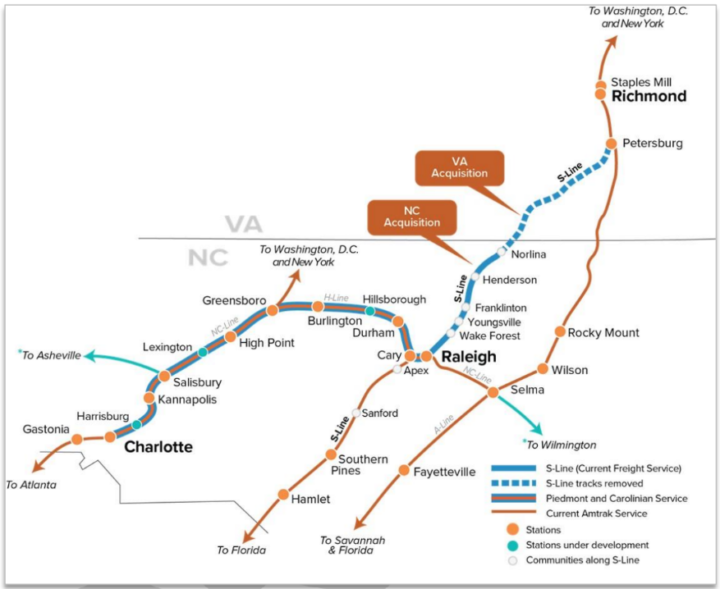

But Gurley contends that passenger rail service in WNC should no longer be relegated to a punchline. An Asheville-to-Salisbury link is included in the 2021 Amtrack Connects Us vision plan, the first public demonstration of federal support for the route. Later that year, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which allocated at least $18 billion explicitly for new passenger lines as part of $66 billion in new rail investment.

North Carolina has jumped on the opportunity. The state DOT submitted the Asheville-Salisbury route to the federal Corridor Identification and Development Program, a newly established effort to support intercity rail planning. And last month, the department released a draft of its WNC Passenger Rail Feasibility Study to better inform conversations about the idea.

Gurley — who’s also a transportation policy adviser and deputy chief of staff to N.C. House Speaker Tim Moore, a Republican — says there’s bipartisan interest in seeing the project succeed. “It’s important for people to understand that no, this is not a joke,” he notes. “We are further advanced in this effort than we have ever been since Southern Railway stopped running passenger trains into Asheville in 1975.”

Nuts and bolts

The final version of the feasibility study is expected next month, following input from the region’s freight railroads and other key stakeholders, says Jason Orthner, director of NCDOT’s Rail Division.

But the substance of the report, he says, is unlikely to change from what the draft lays out. It examines a proposal for three round trips per day on a roughly 139-mile route from Asheville to Salisbury along existing tracks owned by Norfolk Southern. Stops along the way could include Old Fort, Marion, Hickory and Statesville.

The trip would cost about $24 and take a little over 3 1/2 hours, compared with about 2 1/4 hours for the same journey by car. Once in Salisbury, passengers could transfer to North Carolina’s existing Piedmont and Carolinian trains and continue to Charlotte, Raleigh or points beyond.

Potential ridership is estimated at 100,000 local trips per year by 2045, as well as up to 290,000 annual trips by passengers connecting with the Charlotte-Raleigh trains. Even more riders could come from outside the state through the Southeast Corridor, a proposed high-speed rail network connecting North Carolina with Atlanta to the south and Washington to the north.

Those projections are much higher than the roughly 72,000 riders per year estimated by a study conducted for the DOT by the Wake Forest University School of Business in 2001. Tristan Winkler, director of the French Broad River Metropolitan Planning Organization, says several trends have combined to increase demand for train service in WNC.

Most obvious is the region’s overall population growth: Buncombe County alone went from about 206,000 residents in the 2000 census to more than 269,000 in 2020, an increase of nearly 31%. But Winkler says that Asheville’s high housing prices have also pushed many who work in the city to live farther afield. About 1,800 more people now commute from McDowell County into Buncombe than did so a decade ago, he points out, and some of those workers might be able to make the trip by train.

Buncombe has also become more economically integrated with other parts of North Carolina as telecommuting has become more common. About 5,000 county residents have some sort of employment in Charlotte, notes Winkler, and another 3,000 or so have work based in Raleigh. Remote workers, he continues, might still use a train for travel to meetings and other in-person commitments.

Although the technology-driven rise of telecommuting is relatively new, the impulse to link WNC to the rest of the state by rail has a long legacy, says Ray Rapp. A former Democratic state representative from Madison County, he co-directs the WNC Rail Committee and has curated a museum exhibit on the region’s train history.

“We’re trying to firm up the connection between Western North Carolina and the Piedmont and eastern parts of the state. That was one of the goals of 1870s Gov. Zebulon Baird Vance when he helped promote the railroad,” Rapp explains. “We’re talking about, today, one North Carolina. History repeats itself that way, I guess.”

Getting it done

But even if the demand exists, providing Asheville-Salisbury service will require substantial investment. The DOT’s feasibility study estimates some $665 million in capital spending to establish the line, plus $7.3 million to $10.9 million in annual maintenance and operating costs.

Although the route would run on existing tracks, explains Hurley, the current Norfolk Southern line only supports freight traffic and lacks safety features that would be required for passenger service. Many railroad crossings would also have to be upgraded with new signals and equipment to accommodate the faster speeds of passenger trains.

Up till now, notes Winkler, funding has been the biggest obstacle to the region’s push for passenger trains. The new federal support, however, has shifted the conversation. “It’s changed from a theoretical thing to something with a real way forward,” he says.

If the Asheville-Salisbury line is accepted into the federal Corridor ID Program, says Orthner of the state DOT, there will be further opportunities for grants to help pay for planning and construction. The federal government could eventually cover up to 80% of the corridor’s capital costs, primarily through the Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail. State government would fund most of the remainder.

As with any other project, Orthner says the rail expansion will be considered through the state’s Transportation Improvement Program, which prioritizes work based in part on input from regional planning organizations and municipalities. Local governments could also chip in, most likely through improvements to train stations along the route. The French Broad River MPO has asked the DOT to consider a potential Asheville station in the River Arts District in light of the area’s economic boom; according to the feasibility study, using that location rather than Biltmore Village would add about $5 million to the cost of establishing the line.

To put the estimated cost of the Asheville-Salisbury link in context, Winkler compares it to other regional transportation efforts. The Interstate 26 Connector project in Asheville, for example, is currently projected at $1.2 billion, while I-26 widening work in Buncombe and Henderson counties is estimated at $531 million.

Beyond rail’s advantages for passengers, such as less stressful travel and the ability to work while in transit, the line would bring benefits for society at large. Amtrak estimates a $31 million annual economic impact in addition to about $923 million related to one-time capital expenditures. Trains also generate about 80% lower carbon emissions per passenger mile than cars do, making them a more climate-friendly travel option.

All aboard

Like a train itself, the Asheville-Salisbury connector will take a while to get rolling. Amtrak’s vision plan shows a 2035 completion date, and no one Xpress spoke with for this story anticipated the work being finished sooner.

An initial sign of whether passenger rail is likely to move forward in WNC, however, will come much sooner. The U.S. Department of Transportation plans to announce which proposals have been approved for the Corridor ID Program this fall.

And at the state level, Orthner stresses the importance of local support in determining how transportation funds are spent. By lobbying city and county officials to issue formal statements backing the project, he continues, residents can influence the way the NCDOT allocates money.

“Everything in this business is about local interest and local advocacy. It is amazing what projects come about because people want them, will use them and need them,” Orthner explains. “The stronger the message that way, the more they do become real.”

How to get from AVL train to the real mountains up here in apple country is one of the next issues. Trouble is, this train could be 100 years too late– if current global heating doesn’t back off. But it’s good to have dreams as the oceans boil……….

Amtrak has always lost money, except for the Northeast Corridor. The reason the Northeast Corridor is profitable is the high number of commuters.

The biggest problem Asheville faces is we don’t have high paying jobs to attract commuters to Asheville. If anything, I expect people are going to leave town in search of high paying jobs. You’re not going to have any commuters if you can’t guarantee internet access throughout their train travel.

You can’t bring train service to town without bike lanes and good bus service. Planning needs to include dedicated areas at key destinations to lock bikes (not chain them to various poles) and electronic bike rentals. The ART buses holds 2-3 bikes in the bike rack and two additional bikes are permitted inside the bus when those racks are filled: https://www.ashevillenc.gov/service/bus-policies/

With all that said, we are expanding the airport, expanding the interstate, and expanding key side roads. I don’t see rail service as an attractive option; however, I don’t know what I’m missing out on until it is available.

You must be one of our bike zealots. One doesn’t need more largely underutilized congestion causing bike lanes ( see Hilliard) to add rail service.

The problem folks don’t understand is Amtrak allows pedal and electric bikes on their trains.

https://www.amtrak.com/bring-your-bicycle-onboard

I’d be all over it! And if there’s a spur to the airport I’d be in heaven. It could reduce the number of tourists driving here thereby reducing pollution & the number of parking spaces taken by said tourists. Bring it on!!