Of Buncombe County’s $431 million budget for the 2018 fiscal year which began July 1, $137 million — nearly a third — is earmarked for salaries and benefits, up $6 million from the previous year.

County tax revenues fuel a wide range of services, from operating a system of libraries and maintaining a landfill to running the Sheriff’s Department. Behind the books, bins, badges and other amenities is a workforce of over 1,400, making Buncombe County one of the largest employers in the region.

County Human Resources Director Curt Euler oversees this crucial area of county operations. Euler weighs in here with statistics that shed light on county employees’ demographics and tenure, what they earn and how their salaries compare with similar counties across the state.

County jobs are good ones for this area: For the 1,442 people the county employed in fiscal year 2017, the average salary (excluding executives) was $51,965. When executives are factored in, the average was $53,425. Based on the county’s estimated population of just over a quarter of a million people in 2016, there was roughly one county employee for every 178 residents. Those workers served in the following categories: public safety, 603; human services, 584; general government, 169; culture and recreation, 63; and economic and physical development, 23.

Pay for what you get

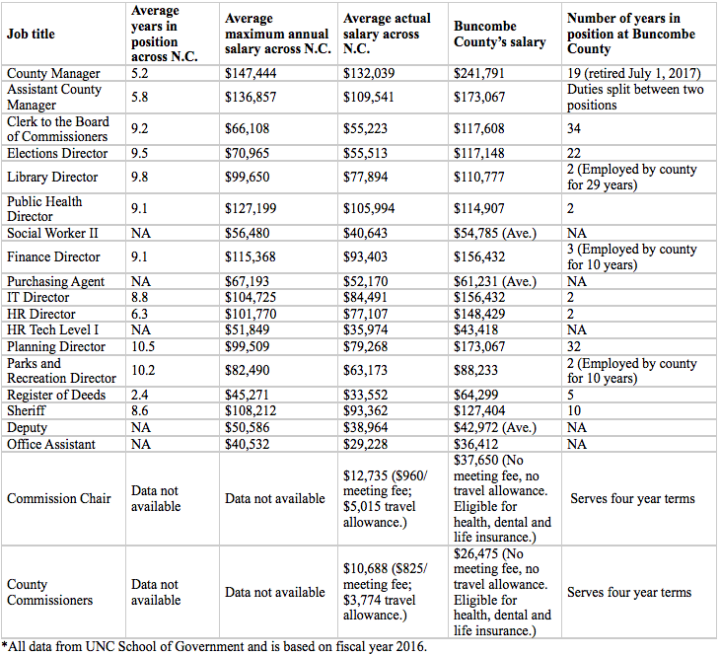

Compared to state averages, Buncombe County’s employees had higher average salaries and longer retention for several key positions, according to information provided by the UNC School of Government for fiscal year 2016. To accurately compare local numbers with the statewide data, all salaries and periods of employment cited here are also from 2016.

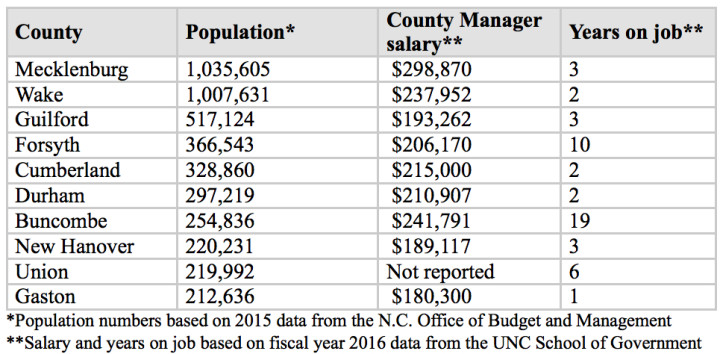

The average annual county manager salary in the Tar Heel State was $132,039, while Buncombe County’s salary for the position was $241,791. That’s a big difference, but Euler warns that measuring Buncombe County against state averages is an apples-to-oranges comparison because of disparities in county populations. Salary figures for the state’s larger counties provide a more accurate context for Buncombe’s pay rates, he says. “The bigger the county you have, the more work there is to do; it’s a scale thing,” explains Euler. “A lot of times you’ll notice experienced, qualified people are at bigger counties.”

Euler says he uses the UNC School of Government data when looking at pay grades for various county positions. He also queries human resource directors in comparably sized counties to help determine the market rate.

According to the state’s Budget and Management Office, Buncombe is the seventh-largest county, based on population. Mecklenburg County, North Carolina’s largest county, paid its county manager $298,870. Tyrrell County, the state’s smallest county, paid its county manager $85,000. The lowest reported county manager salary was Perquimans County’s salary of $37,576.

Another factor that helps explain former Buncombe County Manager Wanda Greene‘s high salary is her length of service with the organization. Across the state, county managers serve an average of 5.2 years in the position. When Greene retired on July 1, she wrapped up 20 years in the post and 23 years with the county.

“We have a lot of directors that have been here for a long time,” notes Euler. The clerk to the Board of Commissioners, planning director and the director of the Board of Elections have held their jobs for 34, 32 and 22 years, respectively. Euler also points out that newer department heads have often been hired internally and usually have been employed by the county for years before being promoted. For example, he notes the library system director has two years in that role but 29 years of experience with the county.

This is also an expensive area, he continues: “I think Buncombe County is a place you have a higher cost of living than other places in the state. For our size, our cost of living is a little out of whack if you compare us to Raleigh or Charlotte.”

Healthy benefits

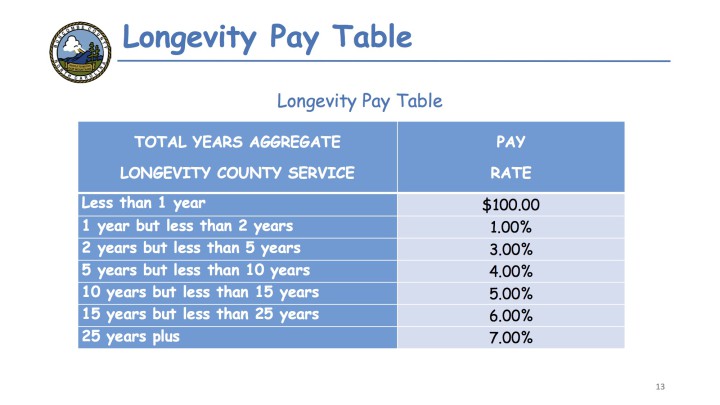

In addition to salary, the county shoulders other employee-related costs, including health and life insurance, retirement, Federal Insurance Contributions Act taxes, 401(k) plan and longevity pay.

Euler explains that, while no system is perfect, the county has opted for a longevity-based rather than merit-based model for pay raises. “Having an equitable merit plan is, in theory, really good, but is hard in practice because you have to establish objectives that are fair to people,” he says. And determining a consistent basis for merit-based performance increases is difficult in an organization with so many job functions and measures of success. “When you’re dealing in human services, you can’t say, ‘You need to close x amount of cases in a day.’ Obviously, I don’t want to penalize a sheriff’s deputy for spending time giving good customer service,” Euler says.

Longevity pay is a percentage of an employee’s salary based on seniority. For example, on the high end, if employees have 25 or more years of service, they receive 7 percent of their salary for longevity pay. Those who have worked more than two years but fewer than five receive 3 percent of their salary for longevity pay.

“Obviously, longevity pay is great: You build up equity the longer you are here. But it’s not really performance-driven. It’s not necessarily your best performer making the money. It’s who’s been here longest, so obviously there are trade-offs,” says Euler.

How long does the average staffer work for Buncombe County? The largest category of employees, nearly 32.6 percent, has worked for the county from one to four years. The smallest category, 4.3 percent, has worked 25 or more years.

The largest age cohort of county workers — which comprises 15.8 percent of its staff — is drawn from those 35 to 39 years old. Workers in the 45-49 age group make up 15.7 percent of the total, while those 40-44 account for 15.3 percent. Young workers in the early phases of their careers are the next-largest group, with those 30-34 constituting 13.6 percent of the county’s workforce. Ten percent of county workers are 55-60 years old, while only 5.4 percent of county employees are 60 or older.

Employees also receive annual raises based on the consumer price index and paid time off. County employees receive 12 sick days, two personal days, and between 10 and 27 annual leave days, based on length of employment. “We have grandfathered plans for people who have been here; they get to keep what they have as plans change,” says Euler.

The monthly cost of the most commonly selected county health care plan is $1,229, with the county footing $1,175 of the bill. The normal annual deductible on that plan is $300. The county does not contribute to family coverage plans.

The best around

In 2014, the county offered an early retirement package featuring an additional year of salary paid out over three years. “You have people that have been around for a while making a high salary. … It’s trying to replace that higher-wage employee with higher longevity and a more robust benefit plan with an employee that doesn’t have as much,” says Euler. The effort netted nearly $1.7 million in recurring salary savings. In future years, more employees will likely take the county up on its early retirement offer. “We have a lot of people that are signed up for 2019, so in 2019 we’ll probably see a bunch of people leave,” Euler reveals.

The demographics of the county’s workforce come close to matching those of the community it serves. As of December, 88 percent of county employees described themselves as Caucasian compared with 90 percent of the county’s residents. Six percent of county workers were African-American, compared with the 6.4 percent of county residents who identify as such. The proportion of Hispanic county residents, at 6.4 percent, is higher than their representation in county employment at 3 percent. Other groups living in the county and employed by the municipality in roughly equal percentages are Native Americans and Asians.

Women make up 54 percent of the county’s staff.

When filling current and future job openings, Euler says, the county will aim for more diversity. “I think we can do better. I don’t think we are where we want to be. That’s going to be something to focus on. … We would love to have people from different cultures,” he says.

However, Euler notes that finding the right person for a job opening can prove difficult, especially when specific skill sets are necessary. And some jobs have statistically higher rates of turnover, such as social work and law enforcement. “Do we have trouble recruiting for them? No. But a lot of times people get into those positions and find out that’s not for them, so people leave. Getting the best of the best, that’s where the challenge lies,” he says.

On June 30, there were six job openings, according to the county’s website. “We usually don’t have a lot … three to six is usual,” says Euler, who notes the county gets about 80 applications per job opening. “We have a lot of qualified people that apply. Not every qualified person gets an interview,” he says. He urges potential applicants to hang in there: “Don’t give up because you’ve been rejected once.”

At the end of the day, Euler says, while the county does spend a significant portion of its budget on employees, “We are always trying to do more with less.” His own department is an example of that philosophy, with only five staffers tending to the hiring, benefits implementation and other needs of the county’s over-1,400-employee workforce.

1. If you have 1400 employees and your average number of vacancies is 3-6, you are paying well above market.

2. The pay for long tenured employees in higher level jobs is way above market. In the private sector, job pay tops out. Here apparently it just continue to increase. When you add breathing pay, I mean longevity pay, on top of base, the salaries are way above market.

3. Sick+personal+vacation time is way above market.

4. Health care benefits are so superior to market that one can’t even see the market from there. $54 a month premium and a $300 deductible. Really? Was this from 1995 and is a misprint?

Oh, and the topper is you can’t be fired and there are no objectives to be met because the HR head says essentially that would be too hard. you’d need to measure things and hold people accountable.

It used to be that govt employees made less and had greater certainty. Now they make more, can’t be fired, have better benefits and are not held accountable. No wonder there are almost no vacancies. This is a travesty.

I agree: the treatment of workers in the private sector sucks. Join a union.

LOL eventually the well runs dry. It will here too. Gimmicks run their course and an area of transplants will move on. When places like Tupelo Honey take in 20k a day and pay their employees 10 an hour and yet are immune to the leftist winbags, something is very wrong.

Candidate filing’s still open if you have a positive plan to ensure the city’s wealth is shared by the working class.

Workers Of The World Unite, y’all.

I agree too. Leadership is it’s own reward because managers get authority and to be the boss. they don’t need pay raises on top of that inherent benefit.

Sure seems pretty top heavy. Would love to see an investigative story about the corruption that is rampant in BC, especially in their hiring practices. Remember the days of investigative reporting?