“There’s this treasure trove of information just sitting there that’s never really been very well mined, because in the past it’s been so complex to run computations against it,” explains Stephen Del Greco, chief of the Data Access Division at the National Centers for Environmental Information. A component of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NCEI is the world’s largest repository of climatological data, and it’s headquartered right here in Asheville, with three other main locations and assorted additional worksites scattered across the country.

NOAA, in turn, is an arm of the U.S. Commerce Department, and commerce is precisely where Del Greco believes this massive accumulation of data will lead those who can translate it into viable new products and services. In fact, after working for the government agency tasked with collecting and stewarding that data for nearly 30 years, he’s making the transition from bureaucrat to entrepreneur himself.

Del Greco believes his new venture, Black Swan Innovations LLC, can help build the local climate science industry. “Folks like myself,” he says, “are ready to bridge from public to private sector. We understand the complexities of these products. … We’ll become conduits between the data that sits at NCEI and the private sector.”

Brainstorm

The confluence of current technological capabilities, forward-thinking entrepreneurs and the federal agency’s data could make Asheville’s climate science industry a source of much-needed well-paying jobs, advocates say.

To that end, The Collider opened in March; the nonprofit co-working space serves science-based startups and established organizations alike. CEO Bill Dean says he sees parallels between the aerospace and defense industry in Huntsville, Ala. (where he formerly worked), and the climate science industry here.

“I watched NASA and the space program, and I remember when people questioned, ‘Why are we putting a man on the moon?’ … and then watched the transition of federal technology to the private sector,” notes Dean, who’s bullish on the climate industry’s job-creation potential. He believes NOAA’s hundreds of scientists and support staff in Asheville could spill over into various private-sector industries, to the tune of maybe 5,000 science-based jobs.

“That’s not uncommon. When I was in Huntsville, we started with 125 rocket scientists and, over the years, it developed into 56,000 people.”

To generate large numbers of jobs, however, our region will have to attract a blend of businesses, entrepreneurs, investors and others. The Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce has been working on that for almost a decade. This January marked the eighth consecutive year that the chamber’s Economic Development Coalition has dispatched a delegation to the American Meteorological Society’s annual meeting, with the mission of making Asheville synonymous with climate science. Clark Duncan, the coalition’s director of business development, says the fight for that title has basically been pared down to three contenders: Boulder, Colo.; Washington, D.C.; and Asheville.

“If you’re a business looking for the best workforce, the best data modelers and climate scientists, for a city of 85,000, we’re on that map for talent concentration,” says Duncan. “There are a few key wins you want to see. The first, entrepreneurial growth, we’re already seeing. Companies with one, two or five employees really flourishing into five-, 10-, 25-person businesses. … That’s a major success for Asheville. The other piece is having some international and national players that are already here bring complementary businesses to the area. Part is homegrown, part is diversification by recruiting some renowned international companies.”

Asheville calling

One such company, the English consulting firm Acclimatise, is using The Collider as a satellite location. CEO John Firth says Asheville called, and he listened. “We realized there’s a potential relationship here that was unique, and it’s just grown from there. So now we see NCEI as our trusted partner. Being in Asheville is the next step for us to grow our business,” he says.

Acclimatise has worked with such corporate titans as IBM, Barclays and Lloyds Bank. “Most of our clients don’t want the data: They just want to understand what it means,” Firth explains. “But we need the data to put that knowledge together, and that’s why NCEI is so valuable.”

Meanwhile, Asheville has also landed the American Association of State Climatologists. Glenn Kerr, the organization’s executive director, echoes Firth’s sentiments. “We’re really excited to be here. We feel we’re getting in on the ground floor of what we expect to be a great growth industry,” says Kerr. “AASC wants its headquarters here to have a direct liaison to the experts at NCEI.”

Now based at The Collider, the national organization will be hosting its 2017 annual meeting there, bringing scientists from every state — and the eyes of the nation’s climate industry — to Western North Carolina. Kerr believes that’s just the type of attention that can keep the city’s climate science industry moving forward.

“It’s a nascent industry; it’s just getting started. However, I think it’s got a ton of untapped potential, and there’s a lot of people that are very interested in bringing that potential to fruition. I think once we have a critical mass of people here trying to provide commercial solutions, you’re going to see a lot of big advances in the areas of climate and health, climate optimizing transportation, and sectors like that.”

Evolutionary leap

So what’s this Golconda of data that everyone’s now eager to mine doing in Asheville — and why wasn’t its considerable potential realized sooner?

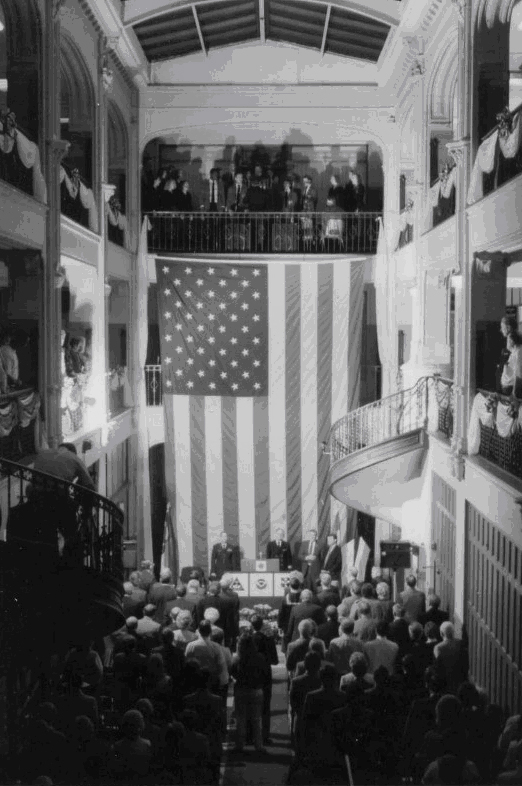

During World War II, the federal government took over the Grove Arcade — by far the largest building in the region at the time — as part of the war effort. After the war, says Mike Tanner, who heads up NCEI’s Center for Weather and Climate, “The U.S. was looking to merge all its weather data … and what they found was the Grove Arcade.”

The National Climatic Data Center, as it was then known, occupied the historic structure from 1951-1995, when the agency moved over to the new federal building on Patton Avenue. In the ’80s, a movement had begun to return the arcade to its original function. The city finally took title to the property in 1997, and after extensive restoration, it reopened in its current form in 2002.

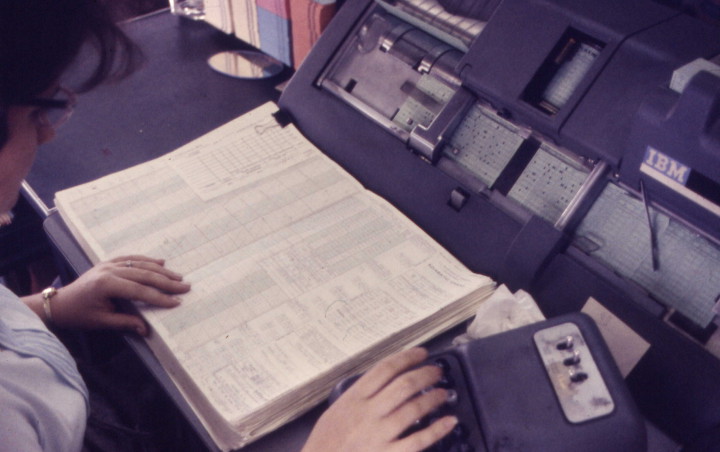

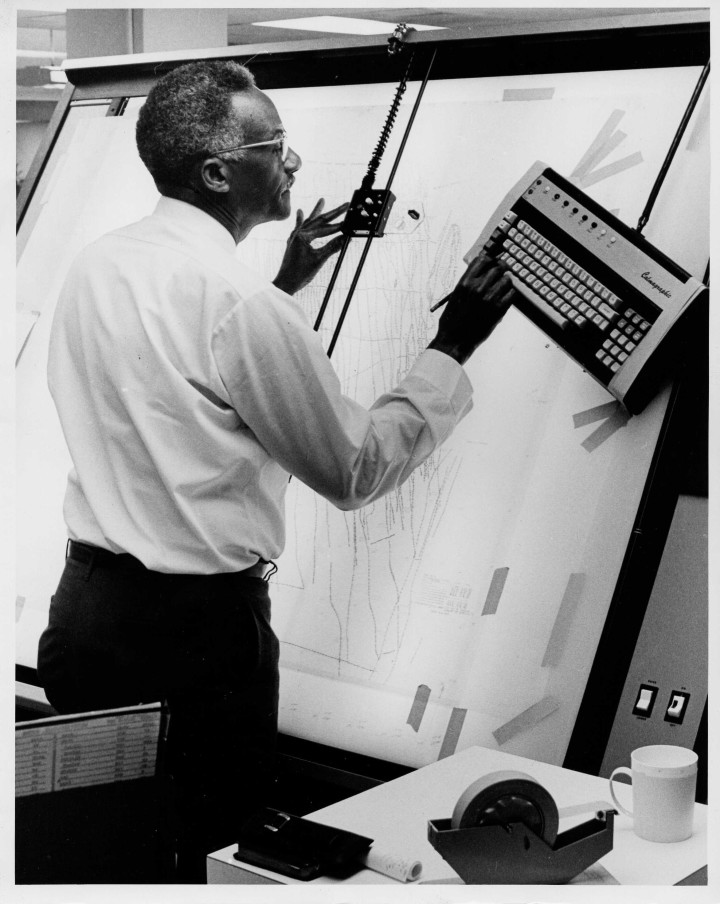

Meanwhile, in the late ’60s, climate data began catching on, notes Tanner, “and we started building products and services out of it. There became a whole new market for this kind of information. All the other technologies associated with that came to Asheville, because this is where the data was. Because of that, scientific, IT and geographic information systems communities came here, along with people who can interpret and write about data.”

The amount of information NOAA oversees is staggering: 25 petabytes, or 25 million gigabytes. That’s the equivalent, says Tanner, of “stacking 120-GB iPhones as tall as the Eiffel Tower 16 times — that’s how much data we have.” Until recently, technological limitations made it hard to efficiently search all that information for trends, but that’s starting to change, and the shift could catalyze a multitude of opportunities.

“I think we’re fixing to go to the next plateau of being able to utilize climate information,” says Tanner. “Because of the high-performance computing capabilities we now have, the entrepreneurs in various industries are dipping into this information. I think we’re going to see, in the next five to 10 years, a leap in the evolution of how this information is used, and people will come here because this is where it’s at.”

From science to services

Duncan, of the Economic Development Coalition, agrees. “Now the technology is to the point where you can do a lot more with managing, visualizing and interpreting data. We didn’t have those tools even five years ago.” He says his organization is excited about the variety of jobs the climate science industry might spawn.

“It begins with the scientists but ends with technologists, consultants, administrators, graphic artists. … Here’s that crossover between technology and the arts that is all about data visualization. A spreadsheet doesn’t make sense to me, but a heat map will make a lot more sense.”

Tanner sounds a similar note. “It might start with science, but it ends with people who can translate that information: writers, public affairs, photographers, IT, computer programmers, visual arts, graphics. … We have a division that’s all communication specialists: people that can write about science in a way the general public can understand.”

Del Greco, the Data Access Division chief, agrees that the tech industry will play a key role in exploring the climate science industry’s new frontier. “There’s a huge IT piece to this,” he says. “There’s complex systems you need to build that provide discovery and dissemination pieces, and that’s all the IT world. It’s great to have scientists, but you need people who can bridge from science to services.”

And as Kerr notes, “There’s a long-standing discussion in Asheville about not having a big wealth of those middle-ground, decent-paying technical jobs. So this is a great opportunity.”

Reverse engineering

Another Asheville-based organization, the Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites, is similarly helping link startups with the data its research produces. “Many climate scientists are beginning to transition from the government to the private sector in an effort to address the challenges and opportunities related to climate change,” says Jenny Dissen, the institute’s corporate relations and strategic partnerships liaison. “Companies are starting to view climate change as a strategic business imperative, and government doesn’t tailor specific solutions and products for companies. As these risks and opportunities continue to be better understood by the private sector, solution providers that understand climate science, climate data and business impacts will be needed to fill the gap.”

Often, The Collider’s Bill Dean notes, a need arises, and enterprising people then reverse-engineer a solution. “Pick up the paper, and there’s things going on in people’s environment that they’re going to have to address. … We can help bring resources to those issues, and that brings more jobs and recognition to the Asheville area.”

One example of a problem in need of solving, says Dissen, is “the critical drought condition in California. The water sector is at a crossroads; this calls for disruptive innovation. Solutions will require access and partnerships across public, private and academic arenas.”

Empty shelves and unsolved cases

According to Del Greco, those solutions may include things like drought-resistant crops and products that help affected states manage risk. But hydrology issues also affect other factors, such as transportation. “The best way to move grain in the Midwest,” he explains, “is on the river.” But when companies can’t do that, “They have to move it on rail or truck. They like to put things in historical perspective so they know the best time to move the largest amount of grain on the river.” Data interpretation, he stresses, is key to predicting river levels.

Firth, too, underscores the importance of supply chain issues, which account for a large portion of his clients’ concerns.

“You can’t have an empty shelf,” he points out. “The supermarket sits at the end of an enormous chain. … The raw ingredients are coming from a farm somewhere. Companies are beginning to realize they need to know where they’ll source the raw materials they’ll need in the future. If coffee growing in Central America is going to be more difficult because of changing temperature and precipitation, where do they go? They can’t wait until the coffee production starts to fall in those countries, because their competitors are already securing that market.”

It seems that there’s almost no limit to the ways that weather data can be used. “Every month we get thousands of calls. … Novelists, private investigators, folks in the Justice Department working cold cases will call us up and ask for the weather in a particular town 30 years ago,” says Tanner. “They might be trying to solve a murder based on the weather. Was it a full moon? Was there a storm? They’re trying to put together the entire puzzle of that particular evening. And many cases have been solved using historical weather information.”

A boon for local schools?

Many advocates believe climate science’s benefits aren’t strictly economic. “It also affects education,” argues Dean. “With more intellectual people coming here, they will want to raise the standards and opportunities for everyone in the region.”

A-B Tech, says Duncan, has done an admirable job of tailoring programs to the needs of the region’s booming craft beer industry, and he sees no reason something similar wouldn’t happen with climate science. “I can see them getting into the sector,” he says. “I can see UNCA bringing additional investments expanding science programs.”

To Anna Priest, executive director of the Colburn Earth Science Museum, that would be welcome news. “North Carolina ranks 36th in the nation in science proficiency, and for every unemployed person in the state, there are 1.7 jobs available” in science, technology, engineering and math, she points out. “We’re helping address this issue by exposing students to STEM education, activities and career paths early, which enhances their interest in STEM jobs later on.” Her institution, which is reinventing itself as the Asheville Museum of Science, hosts more than 10,000 students from 14 counties annually, says Priest. And due to state budget cuts, “A lot of teachers rely on us to help provide that curriculum for their students.”

Del Greco, meanwhile, says, “I’d love to see high school kids who want to do something in science or technology be able to go off to school, get their degree, come back and actually find work in Asheville.”

Weather or not

Despite general agreement that the opportunity exists and the timing is right, it remains to be seen if the local climate science industry will really take off.

“There’s a lot to be done to make that happen, but we have the know-how and the experience,” says Dean. “So if we don’t do it, it’s our own fault, because somebody else is going to. I’m telling you it’s going to happen: I think it’s exciting times we’re in, and the opportunity is ours to develop.”

Kerr believes the next step is making products the market finds valuable. “Once you make those kinds of connections, it’s really going to line up and be pretty easy,” he maintains.

“What I’d really like to see is much like how Silicon Valley is viewed for computer startups: When you start talking about climate science and how it can make things happen internationally, Asheville is the place that happens, and it’s our unique niche.”

Del Greco adds that while some products will take time to develop, there’s plenty of opportunity to hit the ground running. “I see different levels of service,” he explains. “There is low-hanging fruit you can immediately do, and that’s basically the literary piece. Data flows out of NOAA, and you have private sector folks that basically just repackage it. They don’t really even change it much: It’s just more literate.”

Over at NCEI, Tanner says his staff is ready. “We have information services and customer-engagement teams that spend all their time making sure we’re giving the private sector the types of things they need. Whether it’s interpreting science for them or showing them where the data is or how to use it … it’s all about building commerce,” he emphasizes.

Clearly, the interest is there. The agency gets about 18,000 requests each year via phone, email, fax and even handwritten letters, and that doesn’t include the folks using the website to independently mine data. During the 2014-15 fiscal year, the site garnered 1.5 billion unique hits.

“What we’re seeing in the last two to three years is unprecedented — how much information is being downloaded and what they’re doing with it,” says Tanner. “For us to be here and help build industry and public/private partnerships, it’s really what civil service is all about.”

NCEI, he emphasizes, isn’t interested in competing with the private sector. “If we’re building a product and a company comes in and says, ‘We’d like to do that,’ we back away and say, ‘OK, take off, and we’ll help you,’ because we’re here to serve the public good.”

And while climate science remains an emerging industry locally, Duncan says the Economic Development Coalition is already seeing significant progress. “Because of our talent pool, we’re getting looks now from organizations that we wouldn’t have had five years ago. They’re corporate opportunities that tend to come to communities of a larger size.”

Firth, too, believes big things are on the horizon. “We see this as somewhere we are going to grow jobs and contribute to the local economy going forward. I see no reason why, in years to come, everybody in the world won’t know where Asheville is. … In the future, I can see the name Asheville becoming synonymous with climate science and solutions.”

![FOSDIC Dale Lipe Ray Ertzberger mid 60s[NOAA]](https://mountainx.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/FOSDIC-Dale-Lipe-Ray-Ertzberger-mid-60sNOAA-1100x690.jpg)

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.