In May 1923, when Asheville officials approved the construction of a municipal athletic field near Biltmore Avenue, they weren’t thinking about minor league baseball. In fact, the city didn’t even have a team.

The main use of McCormick Field, everyone agreed, would be for Asheville High School athletics.

“This board has gone on record and is most heartily in favor of an athletic field to aid in the physical development and enjoyment of the schoolchildren of Asheville,” city commissioners stated in a resolution, according to accounts in the Asheville Citizen-Times. “Today Asheville is the only city in North Carolina without a field where the schools may engage in athletic sports.”

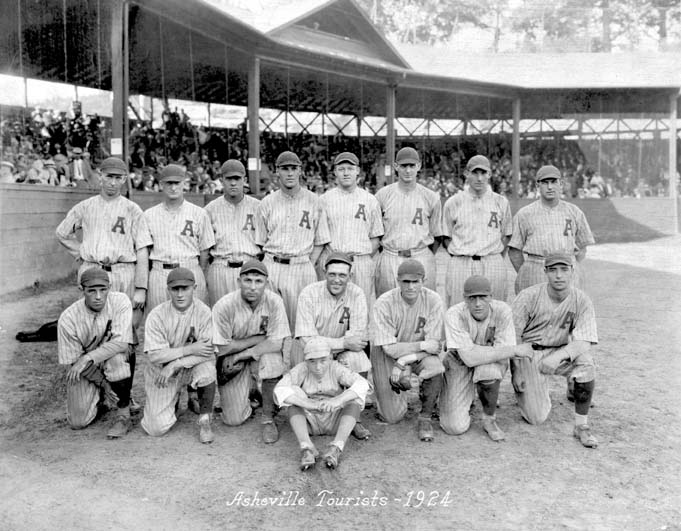

But by the time the stadium celebrated its official opening in April 1924 — 100 years ago this week — its main tenant was the Asheville Skylanders, a South Atlantic League baseball team enticed to the city by the brand-new ballpark. A year later, the team became the Tourists.

Over the past century, McCormick Field has served as the home turf for a succession of baseball teams, ranging from various versions of the Tourists to the Asheville Orioles. Additionally, it hosted all-Black semipro teams, notably the pennant-winning Asheville Blues, in the days when Major League Baseball and its affiliated minor leagues were all white.

But while baseball has been the lifeblood of McCormick Field, the stadium often lived up to Asheville officials’ original vision of a place that would provide “enjoyment and pleasure” to citizens and visitors alike. In the 1930s, it was the stomping ground for Asheville’s long-running Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. The powerhouse Asheville High School Maroons football team of the early 1940s used a devastating running game to demolish opponents on the field.

Over the years, the ballpark witnessed bone-rattling NASCAR races, rocked out to concerts and rolled out the red carpet for movie stars and a president. Through it all, it has sustained itself as one of Asheville’s most iconic gathering places.

“The history there is just unbelievable,” says ESPN‘s Ryan McGee, author of Welcome to the Circus of Baseball: A Story of the Perfect Summer at the Perfect Ballpark at the Perfect Time, which details his 1994 internship with the Tourists. “And it’s not just white dudes playing baseball.”

In honor of the 100th anniversary of Asheville’s venerable ballpark (it’s the third-oldest stadium in Minor League Baseball), Xpress takes a look at 10 of its more memorable moments.

April 3, 1924: Ty Cobb homers

Ty Cobb was 37 and nearing the end of his legendary baseball career when he stepped into the McCormick Field batter’s box as the player-manager of the Detroit Tigers. Just a few months earlier, in September 1923, the Georgia Peach had become baseball’s all-time hit leader, a record that stood until 1985.

The Tigers were in town to officially christen the new stadium in an exhibition game against the Skylanders, and locals buzzed with anticipation at the prospect of hosting one of the nation’s premier athletes. “The greatest ball player that ever lived,” proclaimed the Asheville Times that day. Advertisements in the paper highlighted the opportunity for locals to witness a legend in action.

Cobb didn’t disappoint the crowd of 3,199, launching a home run and scoring two runs as his team fell to Asheville, 17-14. Cobb even pitched the final inning of the slugfest.

Numerous future Hall of Famers, from Babe Ruth to the newly elected Todd Helton, have seen action at McCormick Field over the last 100 years. But Cobb was the first.

Sept. 10, 1936: FDR speaks

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt embarked on a tour of Western North Carolina during his first reelection campaign. His itinerary included stops in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Cherokee, Waynesville, Canton and Candler before he was greeted by thousands of excited onlookers in Asheville on Sept. 9, 1936.

The following morning, the president spoke from his automobile to a crowd of about 20,000 at McCormick Field. During the brief address, which was heard by thousands more via radio station WWNC and three affiliates, FDR praised the region’s natural beauty, according to an account in The Asheville Citizen: “I am carrying out a promise to myself made nearly 30 years ago, because it was nearly 30 years ago that I was last in Asheville, and in those days I said to myself I wanted to come back — I wanted to see all this marvelous country. … I am quite sure that millions of other Americans are going to come down here … and spend more time.”

FDR’s words proved a hit with local tourism boosters. “The speech that President Roosevelt made at McCormick field Thursday morning was one of the finest pieces of travel appeal this section could hope for,” the Chamber of Commerce proclaimed in the Sept. 12, 1936, edition of the newspaper.

Nov. 14, 1942: Charlie Justice’s epic run

“Never before and never since has Asheville, nor indeed the state of North Carolina, seen a high school football team like the 1942 Asheville High Maroons,” longtime Citizen-Times sportswriter and columnist Bob Terrell wrote in 2008.

Playing its home games at McCormick Field — the gridiron ran from the third base line to right field — Asheville went 9-0 that season, racking up victories by such preposterous scores as 94-0, 67-0 and 60-0. The team outscored its opponent 441-6 on the season. Leading the way was Charlie Justice, who would go on to star at UNC Chapel Hill and play in the NFL under the nickname “Choo Choo” Justice. The sensational tailback gained 2,385 yards on 128 runs that year.

Before a capacity crowd of 4,500 screaming fans on Nov. 14, 1942, Justice scored three touchdowns en route to a 27-0 victory over Knoxville (Tenn.) High. One play in particular became legend.

After Knoxville lost the ball on downs just 1 foot short of its goal line, the Maroons set up in punt formation. But Justice received the snap and, rather than punt, galloped 99 2/3 yards for a touchdown without a touch from the opposition. Glancing over his shoulder as he reached the goal line, he noticed not a single Knoxville player standing upright, Terrell writes.

“He was provided with excellent blocking on the first part of the journey, but he eluded a pair of one would-be tacklers around midfield with some of the niftiest hip-shaking the customers could hope for,” Paul Jones of the Citizen-Times wrote the next day.

April 8, 1948: Jackie Robinson takes the field

An estimated crowd of 5,500 braved the rain to see the Tourists host the Brooklyn Dodgers in a preseason exhibition game on April 8, 1948. The defending National League champion Dodgers featured a star-studded lineup that included future Hall of Famers Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese and Gil Hodges. But much of the attention was focused on Brooklyn’s second baseman.

“Jackie Robinson, the first Negro ever to play in the major leagues, received a resplendent ovation from the left field bleachers [the area reserved for Black patrons],” the Asheville Citizen reported. “The fact that he flied out to deep left field in his first appearance made little difference to the approximately 2,000 Negro fans attending. He showed his blinding speed in his second time up but Russ Rose, Asheville shortstop, came up with a neat bare-hand catch and nipped him before he could reach the initial sack.”

C.L. Moore, owner and manager of the Asheville Blues, was in charge of entertaining the Dodgers’ small contingent of African Americans, which included Robinson and catcher Roy Campanella. The Blues, who also called McCormick Field home, had been champions of the Negro Southern League the previous two years.

“Moore … assures us the boys will long remember their visit to Asheville,” Asheville Citizen columnist Red Miller wrote.

July 12, 1958: NASCAR’s Lee Petty crashes

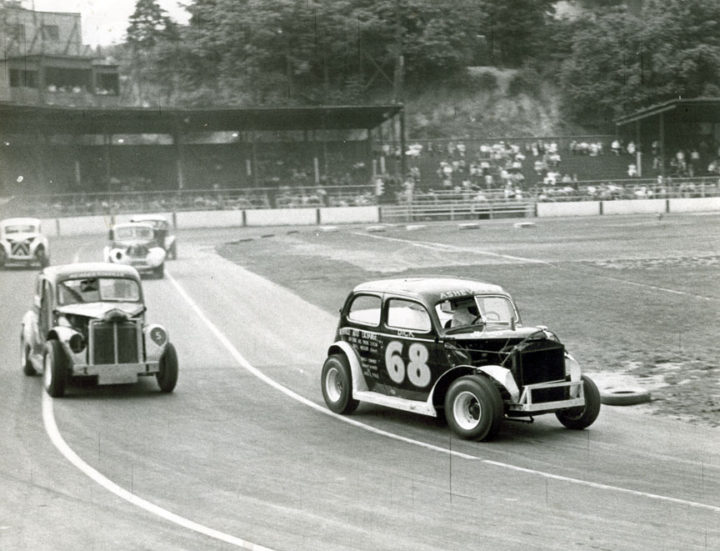

From 1956-58, Asheville was without a professional baseball team, ushering in one of the most colorful eras in McCormick Field’s history.

Jim Lowe of North Wilkesboro leased the stadium from the city and shoehorned a quarter-mile oval track around the tight confines of the baseball diamond. For three years, McCormick Field Raceway hosted weekly stock car races as well as two races in the NASCAR Convertible Series.

Sportswriter Terrell dubbed races at the track “demolition derbies in the round.” Turns out having 25 cars compete on a converted baseball field, with the start/finish line at the hairpin “home plate corner,” made for some chaotic racing.

“Fans were often attracted to the races at the baseball park by the possibility of one or more cars ending up in the first base dugout, a not unusual occurrence,” wrote author Dan Pierce in Mountain Thunder: Stock Car Racing in Buncombe County 1949-1999.

That’s exactly what happened on July 12, 1958, the only time McCormick Field hosted a race in NASCAR’s top series (then called the Grand National, now known as the NASCAR Cup Series). During a heat race that day, legendary driver Lee Petty (father of Richard Petty) “came speeding toward home plate, slipped wildly and went crashing into the first-base dugout,” according to an account from writer Tom Higgins, who was covering the race.

Miraculously, Petty’s team repaired his car in time for him to finish fourth in the main event later that day.

“If you go up in the woods, on the hillside down the left field line, there’s still chunks of the racetrack up there,” says ESPN‘s McGee.

1972: Cal Ripken Jr.’s close call

Cal Ripken Jr. played in 2,632 straight games for the Baltimore Orioles from 1982-98, establishing himself as baseball’s all-time Iron Man. But in the summer of 1972, he was an 11-year-old batboy spending lots of time at McCormick Field because his father was manager of the Asheville Orioles.

Before a game that season (the exact date is unknown) Ripken was playing catch with Asheville Orioles player Doug DeCinces when a teenager in a nearby house broke into his parents’ gun closet and fired several shots into the air from his porch, according to Mark McCarter, author of Never a Bad Game: Fifty Years of the Southern League.

“We’re halfway up the first baseline and I threw a ball and I heard this pop,” DeCinces told McCarter. “All of a sudden there was a whiz and the ground exploded next to me, maybe 10 feet away. I could hear the bullet go by. I was in the Air National Guard and had gone through boot camp and everything registered with me. Like ‘Holy crap, that was a rifle shot.’ And just as that happened I turned and I grabbed Cal on his uniform right at his neck and started to run off the field. I hear another bang and this time the bullet went about four feet in front of me. It was so close. I don’t think Cal Junior ever touched the ground. I went flying into the dugout.”

Ten years later, Ripken replaced DeCinces as starting third baseman for the Baltimore Orioles.

“I didn’t necessarily think I was at risk, but Doug grabbed me and put me in the dugout,” Ripken told The Winston-Salem Journal. “Then I paid him back by taking his job.”

Oct. 5, 1987: Crash Davis comes to town

Most of the action in the acclaimed 1988 baseball movie Bull Durham takes place in, well, Durham. But one of the final scenes of the flick shows veteran catcher Crash Davis, played by Kevin Costner, breaking the fictional minor league home run record at McCormick Field as a member of the Tourists.

Director Ron Shelton picked McCormick Field “because of its look and because [Shelton] saw the park and fell in love with it,” co-producer Mark Burg told the Asheville Citizen-Times in 1987. The stadium still had its original wooden grandstand from 1924 at the time.

A 40-man crew spent about six hours at the ballpark shooting the scene, and about 75 locals, including Citizen-Times reporter and later Xpress writer Tony Kiss, were on hand to portray fans and vendors. Shelton wanted members of the baseball teams at UNC Asheville and Western Carolina to act as players in the scene, but NCAA rules at the time forbade such an arrangement.

One more note: Shelton says he conceived of one of the movie’s most famous scenes — the “church of baseball” speech delivered by Susan Sarandon‘s character — while driving from Durham to Asheville.

“I went right by Black Mountain College, where all these great artists had once taught,” Shelton told Literary Hub in 2022. “And I dictated that first quatrain: ‘I believe in the church of baseball. I’ve worshiped all the major religions, as well as the minor ones. …’ About an hour later, I wrote another couple paragraphs. By the time I got to Asheville, I had that in my briefcase.”

April 17, 1992: A whole new ballpark

Following the 1991 baseball season, Buncombe County spent $3 million to tear down McCormick Field’s rotting wooden grandstand, along with the rest of the ballpark, and replace it on the same site with a brick-framed concrete structure. Among the features of the new stadium were more comfortable and less obstructed seats, expanded concession areas, brighter lighting, a large plaza area, nine 22-foot arches over the plaza walkway and a cantilevered roof covering the middle portion of the grandstand.

On April 17, 1992, more than 4,000 fans showed up on a rainy night to check out the changes. An additional 2,000 or so people were turned away.

“A bluegrass band playing atop the visitors dugout helped create a festive pregame party atmosphere,” the Citizen-Times reported the next day. “The hot dogs were hot, the beer was cold, and the familiar long lines at the improved concession stands formed early.”

Sept. 30, 2006: Indigo Girls perform

The odd bluegrass band aside, McCormick Field had not seen much in the way of live music since the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival left the venue in the 1940s. That changed on Sept. 30, 2006, when about 4,000 people came out to see a performance by Grammy Award-winning duo The Indigo Girls.

The concert marked the first time the stadium hosted a live music concert, the Citizen-Times reported.

“The Indigo Girls show is the first of what we hope will be many concert events, trade show, festivals and local entertainment,” Mike Bauer told the newspaper at the time. Bauer was an official with Palace Sports & Entertainment, which owned the Tourists.

June 22, 2014: Concert draws record crowd

Despite such promises in 2006, concerts did not become a regular attraction at McCormick Field. A notable exception occurred on June 22, 2014, when the unlikely pairing of country duo Florida Georgia Line and rapper Nelly drew 12,000 fans to the venue. It was reportedly the largest ticketed crowd for a concert in Asheville history (and the second-largest ticketed event of any kind, according to an account in the Citizen-Times).

The stadium squeezed that many people in by allowing 8,500 or so fans on the field, with the rest sitting in the grandstand seats.

“The crowd at McCormick Field had ample opportunities to shake its tail feathers — an unprecedented amount of which were (barely) covered in jorts and framed by cowboy boots,” Xpress reporter Jake Frankel wrote in a review of the show. “It was McCormick Field’s first experiment in hosting a major concert event, and it seemed to go off without any major disasters.”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.