An important set of benchmark data detailing the 2018-19 academic proficiency scores for all North Carolina districts and schools was posted online during the first week of October. Xpress downloaded the disaggregated proficiency testing results to assess Asheville City Schools’ recent progress in addressing huge disparities in the academic performance of white and black students.

The district has repeatedly said that reducing the gap between white and black student achievement is its top priority.

As Xpress sought to make sense of the massive spreadsheets, however, questions posed to the state education department revealed that certain data hadn’t been included in the state’s report, an oversight the N.C. Department of Public Instruction said it would correct.

The missing data also caused problems for Dwight Mullen, retired UNC Asheville professor and State of Black Asheville founder, as he prepared a presentation for an Oct. 9 meeting of the United Way of Asheville and Buncombe County. “Finding the data is just not an easy thing,” he said. “It exhausts me because I get angry about it; it shouldn’t be inaccessible.”

Mullen said the information breakdown can have real-world consequences. “If you as a program director in a nonprofit or Asheville City Schools are trying to do something — form a policy or a program based on data — you just don’t have the data,” he noted.

Curtis Sonneman, section chief for analysis and reporting at NCDPI, explained the omissions. “After your call, I did some digging,” he told Xpress. “We have identified a masking rule that was applied a little excessively, and we’re putting a new report out early next week.” He also directed Xpress to another report that contained the missing data — a huge spreadsheet file of over 100 megabytes.

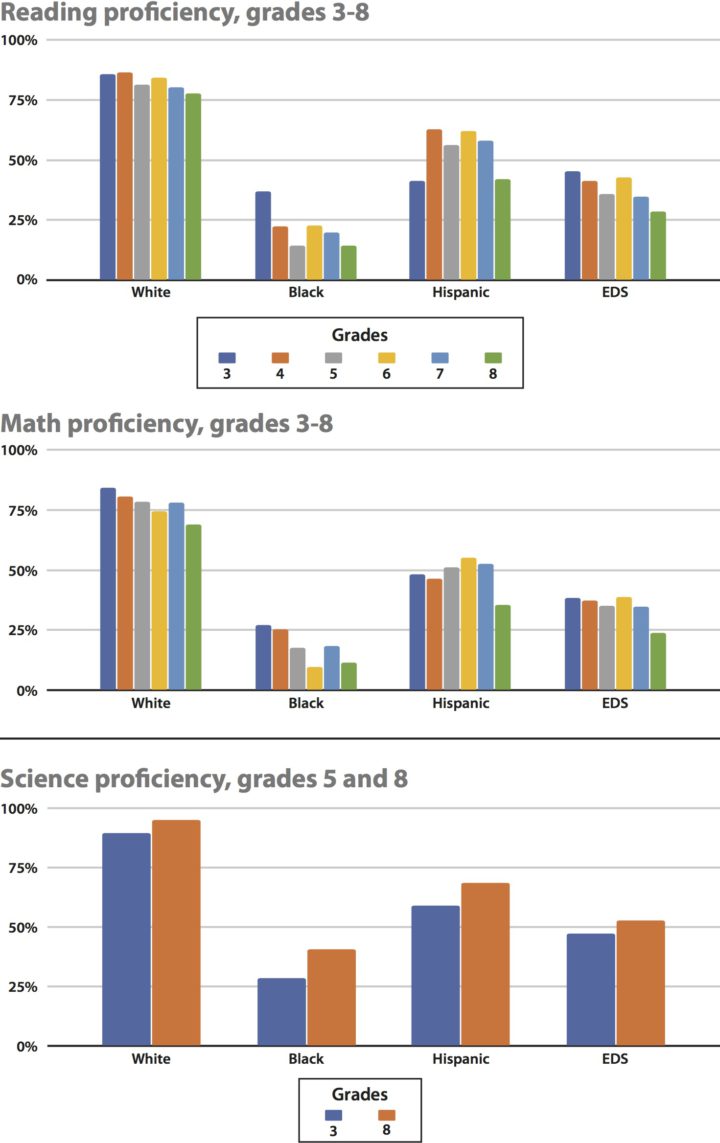

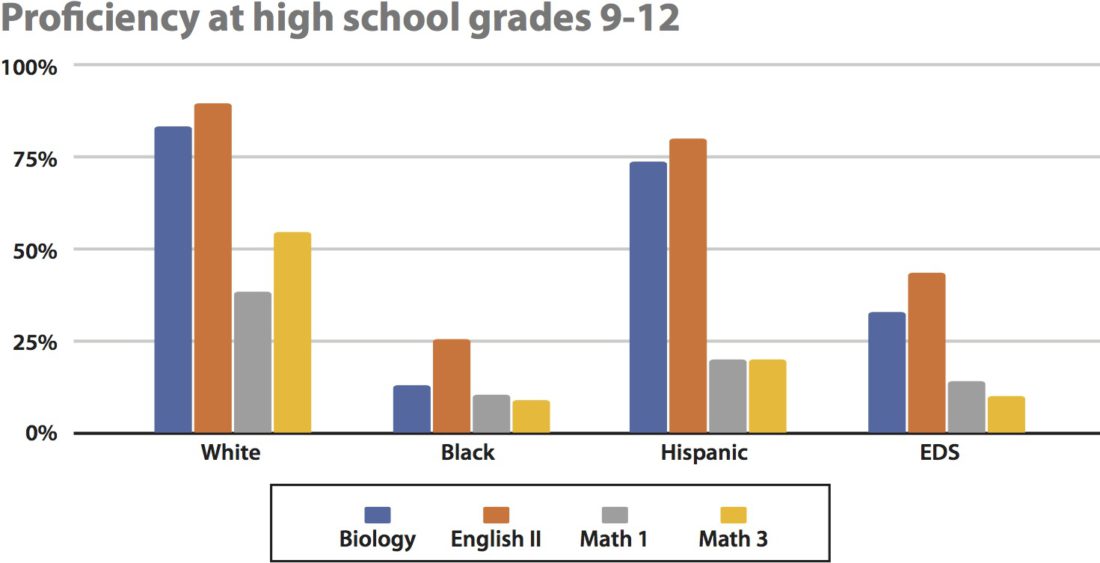

Based on the data available to him as he researched the city schools’ most recent results, Mullen found much that gave him pause. For example, at Asheville High School, only 9.1% of African American students scored at or above grade level on the Math III end-of-course test. “But when you look at the percentage of African American students passing the Math III class, it’s over 80%,” he said. “Now how can you be proficient at the 9% level, but yet 80% of y’all passed the class?”

The same concern applies to graduation rates, he continued. “It looks as though black students are graduating from Asheville High at a very reasonable rate relative to what’s going on across the state,” he said. “What kind of quality of education are students receiving with those diplomas? And I don’t have a lot of faith.”

Back to school

Dana Ayers, chief academic officer for Asheville City Schools, said there are bright spots in the data. “Definitely with proficiency, we are seeing pockets of strength and pockets of areas that we’re superproud of,” she said. The data is reviewed at monthly administrative meetings with district principals, central office personnel and directors, she explained.

For example, Ayers continued, “At our September meeting … principals sat down and talked about holistically, as a district, areas of strength that we see and areas that we can continue to excel and continue to grow our kids, both in their proficiency level but also in their growth.”

Asked what specific areas of strength the district had identified, Ayers pointed to its highest-ever graduation rate of 90.7%. While few would dispute the importance of that figure, it’s not directly related to academic proficiency test results, as Mullen pointed out.

“Fifth grade math showed some really positive improvement, as well as the fact that we didn’t have any schools that were rated D or F,” Ayers added.

Focusing on student cohorts by grade provides a more accurate picture of progress than analyzing year-over-year performance, Ayers said. “When you look at a cohort group, you’re looking at the same kids’ progress over time,” she said. ”If I’m in the third grade, I don’t want to compare me to last year’s third graders, because that wouldn’t be an accurate picture.”

Accurately comparing a cohort’s results, however, was impossible without the information the state says was inadvertently omitted from the disaggregated data. Students in grades three, four, six and seven take two end-of-grade tests per year (in math and reading), while fifth and eighth grade students take three EOGs (math, reading and science). Before the new release of data, each individual test result was included in the composite proficiency numbers sorted by grade. The number of results in each cohort thus varied significantly by year, rendering comparison statistically meaningless.

At the high school level, students take four end-of-course tests: Math I, English II, biology and (new in the 2018-19 school year) Math III. Students take these courses in different years; depending on previous coursework and other schedule considerations, for example, a student might take Math III as a sophomore, junior or senior. Given this variability, comparing results for a specific student cohort across time becomes even more complex. “It’s all about when they’re taking those classes,” Ayers said.

Bucking the norm

Yet another factor that could complicate comparisons between school years is changes to the tests and how they are scored. “Our math scores are based off a newly normed test. So the math test that our students took in grades three-eight, this is a brand new state assessment for them,” Ayers said. “Typically, on a year that a newly normed test comes out, we have a dip statewide, not just districtwide.”

Sonneman, the state official, disagreed with Ayers’ assessment. “It’s not a normed test, and so we don’t renorm it,” he said. The correct term, he explained, would be “standard setting,” which occurs when a panel of teachers establishes what students should know and be able to do at, in the case of mathematics, each of four proficiency levels. (Reading, English and science are scored at five proficiency levels.)

He also disputed Ayers’ characterization of the statewide impact of new standards. “In some grade levels, mathematics went up, some grade levels went down, depending on what you were looking at,” he said. “But generally speaking, there wasn’t a significant shift in one direction or the other.” A summary of state testing results for the 2018-19 school year is available at avl.mx/6me.

Tests taken at the end of the current school year for reading and English II, Sonneman said, will be based on new standards.

Ayers stressed that all the data is available to the public. “If you Google NCDPI test results, you can find that,” she said. But when asked whether the district will make any of its analysis available alongside those numbers, she said there are no current plans to share that information.

“Any of the data analysis that we do individually, either by grade level or at a school, that’s kept in-house, because that’s what we use to guide our instruction. It’s the same data, it’s just the way we disaggregate it and look at it,” Ayers said.

WTF?! Is this White Privilege through institutional bias in the South at its finest? Wonder if there’s class action lawsuit in there some where for cheating folks out of their right to an education? Makes the placement of minorities in high ranking county and city positions seem like nothing more than tokenism. Way to go progressive, elitist Asheville.

Let’s see the same performance data but including kids with learning differences, i.e., disabilities and delays, and also broken down by gender and sex.

The quickest and most reliable way to eliminate the “gap” is to degrade the performance of everybody.

government screwls….ACS is a heinous school system run by elitist exclusionists …