As the workday ended June 1, some workers at the Moog Music factory on Broadway in Asheville beelined to their vehicles and bikes.

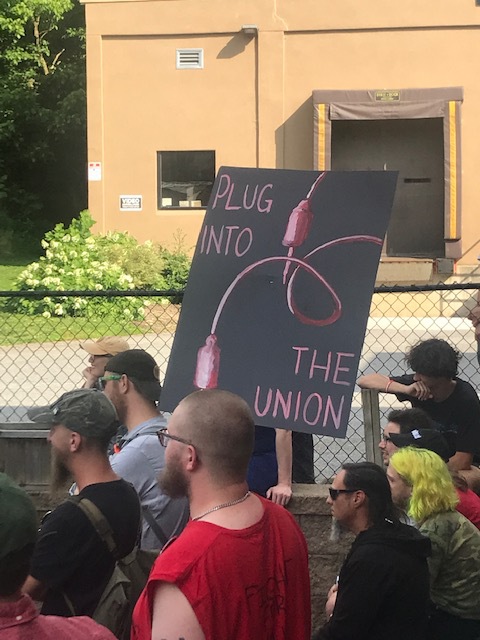

But as the minutes ticked past 5 p.m., a crowd of about 50 Moog employees and their supporters gathered in the outdoor area of nearby Archetype Brewing North with banners and signs. The occasion: the launch of a campaign for Moog workers to join the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 238.

Amid chants of “Synthesize unions!” past and present Moog employees spoke passionately about their jobs manufacturing state-of-the-art electronic instruments played by musicians worldwide. But they also spoke of low pay, insufficient raises and broken promises by management.

Korey Crisp, who uses they/them pronouns, joined Moog in late 2021 and contacted IBEW earlier this year to inquire about organizing with several other workers. “We started learning more about our rights and the things that companies can and can’t do,” they say. “We realized that this is probably the best move for all of us.”

The union effort at Moog comes at a time when labor organizing in North Carolina appears to be on the upswing. Ten businesses in the state contacted the National Labor Relations Board about representation during all of 2021; 13 have done so since the beginning of 2022, including two in Western North Carolina.

WNC saw a major successful labor effort in 2020 as nurses at Mission Hospital joined National Nurses United, and efforts in the service sector have been galvanized by the 2021 formation of labor activist group Asheville Food and Beverage United. In April, a Starbucks in Boone became the chain’s first coffee shop in North Carolina to be represented by a union. (A 2019 union campaign at Earth Fare was not successful, nor was a 2020 effort at No Evil Foods.)

These recent unionization efforts may be part of a national trend. The NLRB reported a 57% increase in union representation petitions filed Oct. 1-May 1 compared with the same period in fiscal year 2020-21.

Claire Clark, housing and wages organizer for Asheville nonprofit Just Economics WNC, tells Xpress that grappling with American work culture during the COVID-19 pandemic has newly catalyzed workers.

“We heard throughout this pandemic about essential workers, workers as heroes, and people are looking around and saying, ‘Well, what does that mean in material terms?’” she says.

Many workers realized a livable wage and safety precautions weren’t prioritized by their employers or the government, Clark continued. “They left workers out to dry while they bailed out banks and Wall Street,” she says. “People on Main Street want some of that too and deserve it. Because workers are the people that make the world run.”

Better together

North Carolina was the nation’s second-lowest state for union membership in 2021, according to the federal Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics. Keith Rivers, an international lead organizer for IBEW and electrician from Winston-Salem who attended Moog’s June 1 rally, says organizing hasn’t progressed in the South as it has elsewhere.

Workers are generally employed “at-will” in North Carolina, Rivers explains, meaning they can be fired or reassigned as the employer sees fit. “It makes it a little tougher for people to come together,” he says.

“With the South being traditionally nonunion and a lot of misinformation out there about unions, people are turned against it before they even give it a chance to see what it’s about,” Rivers continues.

Asheville-based organizer Jess Kutch, co-founder of CoWorker.org, a nonprofit advocating for worker rights through digital campaigns, suggests that the legacy of slavery undergirds some of the region’s historical resistance to unions.

“I have begun to question this belief that, ‘Oh, just the South isn’t interested in unions,’” Kutch says. “The more I have dug into that, I found that [it is] because of the South’s history of slavery, anti-Black racism and violence against Black people and Black workers in particular who tried to organize.”

As one example, she cites the 1887 Thibodaux Massacre, when white vigilantes murdered as many as 60 sugar cane workers in Louisiana who had gone on strike.

‘Best interests’

At Moog, says Crisp, employees are demanding $17.70 per hour as a starting wage, based on the 2022 living wage for Buncombe County calculated by Just Economics WNC. Currently, according to Moog’s volunteer organizing committee, the company pays a starting wage of $14 per hour for packing, warehouse and assembly positions. (Moog declined to confirm its starting wage.)

Workers also want to see more transparency from Moog’s management regarding layoffs. Crisp was let go in May after six months of working for Moog; they say the reason given by management was restructuring. A press release from the organizing committee, sent by member and mechanical engineer Catherine Hebson, also alleges two people recently laid off by the company had participated in the committee.

When asked to confirm this allegation June 13, Jeff Touzeau of Hummingbird PR, which represents the company, declined to comment. He directed Xpress to a June 10 statement he had sent in response to a request for comment on the unionization effort.

“Moog Music Inc. is aware of the unionization campaign launched by the IBEW 238 and a group of Moog Music staff members,” that statement reads. “We respect that our employee-owners have the right to join a union, and we will not do anything to interfere with their right to do so.

“We have engaged outside resources to help ensure our company navigates the aforementioned union efforts legally and with proper guidance,” the statement continues. “While we don’t believe a union is in the best interests of our employee-owners, we will ensure that everyone at the factory has access to accurate information about unions and what a union would mean at Moog so that our employees may make their own informed decisions.”

(Moog President Michael Adams announced in 2015 the company would become 49% employee-owned through an employee stock ownership plan. An ESOP allows employees to cash out shares of the company upon retirement.)

Moog’s organizing committee declined to share with Xpress the number of signatures collected in the unionizing effort; the NLRB requires 30% of workers to sign cards or a petition seeking a union before an election can be held. “There have been an increase in signatures, and we’re working diligently to hit our threshold of cards signed,” the organizers write in an email.

Try, try again

The fate of another recent organizing effort has already been decided. On May 11, employees at the Starbucks on Charlotte Street in Asheville voted 11-6 to reject representation by Workers United.

Among the changes union advocates had hoped to address through collective bargaining with Workers United were advance scheduling, a $15 hourly starting wage and the addition of credit card tipping.

Management at the local Starbucks location directed Xpress to the Starbucks corporate communications office, which has not responded to a request for comment.

But Jen Hampton, a lead organizer for Asheville Food and Beverage United, says the effort has nevertheless inspired other workers. On June 15, she told Xpress three independent restaurants had invited AFBU to staff meetings to discuss walkouts, and five had reached out about filing petitions to unionize. The campaign is planning an information session in July.

“People are interested in getting training on their rights in regards to unionizing,” Hampton says. “There’s been a lot of people asking how to go about filing complaints regarding wages and tips. And another person reached out to find out if they had any recourse for posting [work] schedules the night before.”

How the labor movement reignited by the pandemic will continue to unfold in WNC remains to be seen. Yet Kutch of CoWorker.org remains optimistic.

“The history of building worker power in the labor movement is littered with losses. But those, together with the victories, amount to workers actually holding real power in the economy,” Kutch says. “The losses are common, they’re inevitable, and they’re part of the fight.”

Following the unsuccessful Starbucks vote, Kutch says she reached out to a barista who had led the campaign to encourage her that even unsuccessful union drives can be worthwhile.

“I imagined she was feeling really down in the dumps, but I wanted her to know that that campaign was deeply meaningful,” Kutch tells Xpress. “It meant something to other workers in the area.”

She adds, “I encourage people to take a long view, no matter the outcomes in the immediate sense.”

Edited at 12:17 p.m. June 23 to correctly attribute statements from Moog union organizers.

This is great news! More jobs moving or coming soon to upstate SC!

Who wants to work at Moog or Starbucks anyway?

I can’t help improve myself so I need a union to do it for me.

The Starbucks one was great. I love people overestimating their worth.

The only reason we have minimum wage and 5 day/8 hour work weeks is because of unions. But sure, please make this somehow about personal worth and not the worth of society’s workforce as a whole.