There’s a chasm separating what statistics say about the Asheville area’s current rental landscape from the actual experiences of people seeking a place to live. Real life doesn’t seem to be reflecting the data — at least, not yet.

Emily Coates, 29, is a professional photographer who moved to Fletcher in August. Buddy Chambless, a 65-year-old retiree, has lived in Asheville for more than four years. Different in many ways, both have struggled to find affordable rentals here — an all-too-familiar ordeal for many locals.

For Coates, who’s currently looking to move again, that’s meant focusing on communities more than a 20-minute drive from Asheville, such as Fletcher, Black Mountain and Hendersonville. Chambless, a West Asheville resident on a fixed income, says he’s had to “live in less desirable areas and in substandard physical facilities,” an experience that “really has made me feel ‘less than’ and like some type of lowlife.” He pays $550 a month for “a very small one-bedroom apartment,” plus utilities.

Renters on the hunt tell a well-worn tale: There are precious few decent, modestly priced digs in Asheville and environs, and getting one often requires some combination of creativity, compromise and luck. Yet according to the most recent data available, the vacancy rate is increasing, and while rents continue to rise, the rate of growth slowed over the past year.

Nonetheless, by mid-January, Coates had been looking for three weeks and hadn’t found anything in Asheville for less than $800 a month. “The prices keep going up and up and up,” says Coates, who shares her renovated barn in Fletcher with a roommate. Their $750 rent does not include utilities. “That just makes the economy weaker. If that keeps happening, it’s going to be difficult for people who want to live here to thrive.”

Dueling numbers

During last year’s fourth quarter, the rental vacancy rate in Buncombe, Haywood and Henderson counties stood at 7 percent, says economist Barbara Byrne Denham of Reis, a New York City-based real estate research firm. That’s slightly higher than the 6.8 percent vacancy rate Reis reported during the third quarter of 2016.

Either figure represents a huge improvement over the 1 percent vacancy rate that the Ohio-based Bowen National Research cited in a January 2015 report covering Buncombe, Haywood, Henderson and Transylvania counties. The same report found an even lower rate in Asheville and Buncombe County. In December, the real estate market consulting firm issued a new report that looked only at Buncombe. As of the end of 2016, it said, the county’s rental vacancy rate had risen to 2.7 percent. The city paid Bowen $29,750 for the 2015 assessment and $4,500 for the update.

During a Jan. 17 meeting of City Council’s Housing and Community Development Committee, Council member Julie Mayfield said the city should stick with Bowen’s numbers. “We’ve used the Bowen report, and we’ll continue to use the Bowen report, so it’ll be apples to apples,” said Mayfield.

But Jeff Staudinger, Asheville’s assistant director of community and economic development, and Barry Bialik, who chairs the city’s Affordable Housing Advisory Committee, argued that local policymakers would benefit from having such additional data.

Committee members, however, unanimously recommended to City Council that Bowen conduct another assessment at the end of this year to track changes.

Affordable vs. market-rate rentals

To produce its December report, Bowen researchers surveyed 105 multifamily rental properties. Reis surveyed the units in 58 multifamily developments. Both surveys considered rentals of various sizes.

Experts consider 5 percent to be a healthy rental vacancy rate, meaning it’s low enough “that landlords are filling their units easily,” says Denham. “There is always turnover in leases, so a 5 percent vacancy accounts for that turnover and the need to paint and touch up a unit between leases.”

Both Bowen reports, though, found the vacancy rate for “affordable” rentals, such as subsidized housing, to be essentially zero percent. More than 550 people were on waiting lists for such homes, according to the December update. And while at least 1,500 new rental units have come on the market in the last two years, the vast majority of those have been market-rate, notes Patrick Bowen, the firm’s president.

Nonetheless, Asheville City Council member Gordon Smith applauded the increase in supply, saying, “We need more housing across all price points.” Although the influx of new market-rate rental units has alleviated Asheville’s “severe shortage, the affordable housing crisis persists,” continued Smith, who chairs both the city’s Housing and Community Development Committee and the Asheville Regional Housing Consortium.

A glance at the region’s rental rates (excluding utilities) supports that contention.

The median “asking rent” in Buncombe, Haywood and Henderson counties rose to $1,044 in the third quarter, from $1,016 in the previous quarter, Reis researchers found.

Bowen, meanwhile, reported in December that since the close of 2014, the median rents for studio, one-, two- and three-bedroom units in Buncombe County had increased by an average of $140 monthly. The update reported median rents ranging from $875 for a studio to $1,127 for a three-bedroom unit.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development calculated affordable rents for the Asheville metropolitan statistical area — a federally defined region comprising Buncombe, Haywood, Henderson and Madison counties — as $685 for a studio and $1,116 for a three-bedroom unit.

The view from the street

No wonder Asheville has a housing crisis, says the Rev. Amy Cantrell.

“When we still see, at any given time, hundreds of people with incomes who are still homeless, then we still have a housing crisis,” says Cantrell, who runs BeLoved House, a homeless support and transitional living facility near downtown. She’s also the community organizer for Just Economics of Western North Carolina, an Asheville-based nonprofit that advocates for a living wage and a sustainable economy.

Scott Dedman, executive director of Mountain Housing Opportunities, sounds a similar note. “The slight easing of the market for middle- and upper-income apartments, though a positive trend, has not helped those who can’t afford a middle- or upper-income apartment,” he points out. MHO builds and renovates homes while helping people find affordable places to rent and buy.

“If you make $10 or $12 an hour in Asheville or Buncombe County and you have only one earner in your household, there is no easing in the housing market yet for you,” says Dedman.

But Denham, the Reis economist, downplays such talk.

“Rents are still below $1,000 per unit,” she points out; the company’s methodology employed a weighted average of rents for units of different sizes. “While I could see residents worrying about gentrification and the rising cost of housing given the newer high-end construction, the numbers do not substantiate the claim that costs are rising significantly. This story and fear is heard across the U.S. in a number of metros both big and small.”

Vacancies galore?

Some developers go much further, predicting that before long, there’ll be a glut of rental housing that will cause rents to fall and deter additional projects. With up to 1,400 rental units currently under construction, says developer William Ratchford, the area’s vacancy rate could soon rise so high that his company might not want to build additional rentals here.

Bowen researchers say the number of rental units now being built is much higher. City officials worked with Patrick Bowen to correct some figures in the December report, concluding that 1,970 multifamily rental units are under construction, with another 2,677 “planned or proposed.” Most of those units — 3,799, or 81.8 percent — will be market-rate rentals.

Denham, on the other hand, simply says, “We see vacancy ticking up a bit in Asheville” from 2017 through 2019 “due to the new construction.”

Ratchford, who’s vice president of Southwood Realty Co. and Triangle Real Estate in Gastonia, also cautions that actual vacancy rates are probably higher than what property managers report. “People lie about them,” he explains. “Banks start asking questions if the occupancy rate falls below 90 percent.” Ratchford, whose companies have built several rental developments in the Asheville area, says, “We’re starting to worry that the market is becoming oversaturated.”

That would be good news for folks like Coates and Chambless.

“Now is the time that rents actually are going to start to come down,” Ratchford predicts.

That hasn’t happened yet, though the rate of increase has slowed. In the three counties Reis looked at, says Denham, “Rent growth was 5.3 percent in 2015 and should be at or just below 3.5 percent for 2016. Both of these rates are in line with the U.S. average.”

Bowen’s December report, on the other hand, says that nationally, the rate of increase was 3 percent in 2016, and market rate rents in Buncombe rose 4.4 percent during that period.

Good news

The $74 million bond issue that Asheville voters approved in November will include $25 million for affordable housing. The city’s Housing Trust Fund, which makes low-interest loans to help developers build affordable housing, will receive $10 million of that money, says Smith, and City Council will decide how to spend the rest. One option he’s asked staff to explore is building hundreds of affordable apartment units on land the city owns on South Charlotte Street.

The $15 million could also be used for land banking, notes Staudinger. This strategy involves buying suitable parcels at current prices and reserving them for future affordable housing projects. It’s most effective, he explains, in areas where property values are projected to increase steeply. If that happens, this could enable the city to provide housing in prime locations at much lower cost than the surrounding residences.

The bond issue’s affordable housing component will also enable Asheville to allocate more money to specific projects each year, says Staudinger. In recent years, City Council has typically budgeted about $500,000 for affordable housing, he points out. Against that backdrop, having $25 million “exclusively for affordable housing over the next five to seven years is significant. This is really good news.”

Tweaking the rules

In December, City Council approved several changes to the Housing Trust Fund aimed at making it easier to build affordable housing. These included: increasing the maximum loan amount from $500,000 to $1 million; explicitly making tiny homes, container homes and other innovative approaches eligible for loans; and giving smaller projects the same priority as larger ones in an effort to get more builders involved.

Meanwhile, the 2015 expansion of Asheville’s land-use grant program has begun yielding results. The expansion made grants available for both “affordable” and “workforce” apartments; the move has drawn praise from experts across the state.

“This could make a dent in Asheville’s affordable housing shortage,” says Samuel Gunter, the director of policy and advocacy at the N.C. Housing Coalition in Raleigh. “The incentives allow developers to get returns on their investments close to market rates.”

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines affordable and workforce rents based on median incomes in each of the country’s metro areas. Affordable rents target those whose household income is no more than 80 percent of the median for the area. Those qualifying for workforce rents can have household incomes up to 100 percent of the median. In the Asheville metro, the median income for a family of four was $57,900 in 2016, according to HUD.

To qualify for a grant from Asheville’s land-use program, at least 10 percent of the project’s units must be affordable or workforce housing, and rents must remain at those levels for at least 15 years. If a grant recipient violates the terms of the agreement, the city reclaims the land, Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler noted during the Jan. 17 committee meeting.

Grant amounts are calculated based on the city property tax for the new development and a formula that awards points for various aspects of the project, Staudinger explains. The grants may include a percentage of city building permit fees, and developers may reap additional benefits by increasing the number of years those rents remain at affordable or workforce levels.

Planned projects

Since May 2015, the program has funded four projects with grants totaling about $1.8 million. The final amounts will be determined upon project completion.

In May 2015, the RAD Lofts development in the River Arts District was awarded about $580,000. Despite substantial delays, Harry Pilos still plans to proceed with the massive $60 million project. Plans call for about 227 apartments, ground-level retail and almost 400 parking spaces. About 95 percent of the units would be workforce housing; the remaining 12 or so would be for low-income residents. Rents would be kept at affordable rates for at least 15 years.

In July of last year, Biotat LLC, the contracting company for Griffin Realty and Construction Enterprises Inc., received a roughly $457,000 grant. Asheville developer Ward Griffin plans to build a 72-unit apartment complex at 29 Oak Hill Drive in West Asheville, with half the units reserved for renters earning up to 60 percent of the Asheville metro’s median household income. Those apartments would remain at the affordable rate for 15 years. The other 36 units would be workforce housing and would remain so for 20 years.

Last October, Beaucatcher Commons LLC was assigned about $296,000 for a 70-unit apartment complex to be built by local developer Kirk Booth of Kirk Booth Real Estate. All of the apartments at 43 Simpson St. would be for households earning up to 60 percent of the median income and would stay at that rate for 20 years. Construction could start by the end of this year.

And in December, City Council awarded the Atlanta-based Hathaway Development about $530,000 over three years for a four-building complex in South Asheville. For at least 15 years, 10 percent of the 290 planned apartments will be reserved for tenants who qualify for affordable housing. Located at 55 Miami Circle and 70 Allen Ave., Skyland Exchange will include one-, two- and three-bedroom units, with projected rents ranging from $850 to $1,350. But those figures could be adjusted, noted Hathaway, depending on the market conditions when the apartments are ready to rent. The first units could be available as early as next January.

Repurposing city-owned land

Another innovative project aims to take advantage of property the city already owns. Asheville issued a request for proposals for a 0.8-acre parcel at 338 Hilliard Ave. last May. Currently the site of the city’s park maintenance facility, the property will become available when that facility moves to a new address this year, Staudinger explains. The parcel, he adds, represents “the first repurposing of city land for housing.”

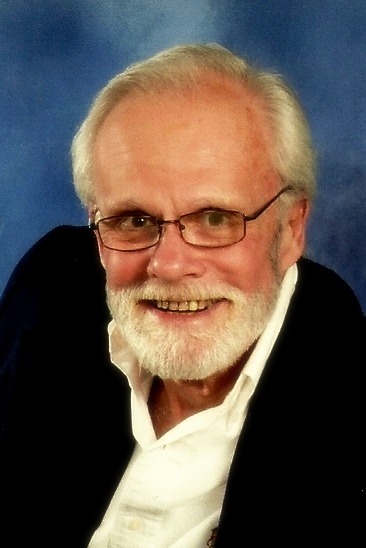

longtime city staffer and current assistant director of community and economic development, has recently announced his retirement. File photo

Proposed projects had to include at least 40 units. The Wilmington-based Tribute Cos., a real estate development, management and investment firm, won the bid in August.

“We’re in negotiations with the city now,” says Paul D’Angelo, the company’s director of affordable housing. The project is a first for Tribute, he notes, adding, “If it works, we’ll repeat it elsewhere.” Hired by the company in February 2016, D’Angelo was formerly the Wilmington Housing Authority’s planning manager.

Tribute executives, he continues, have chosen to enter this market because they understand “the real need out there. We want to be part of the solution.” And though such projects are expensive to build, the Asheville venture “has the potential to create partnerships down the line.” The company will pay $450,000 for the property and plans to apply for a land-use grant worth about $308,000.

Rents in the four-story complex will depend on the unit’s size. Forty-two of the apartments will be affordable by those earning up to 80 percent of the metro’s median income. That total will include units for the homeless and those earning 30 percent and 60 percent of the median. The remaining 18 will be at workforce rental rates. Rents will remain at or below the rates in each respective category for 25 years. The 60-unit complex could be completed by spring 2018.

On Jan. 17, the Housing and Community Development Committee unanimously approved recommending the project and its terms to City Council.

Thinking big

Not all the planned projects are being done by private companies, however. Asheville Area Habitat for Humanity is proposing a 100-unit development for another city-owned parcel, this one near the intersection of Pisgah View and Deaverview roads in West Asheville. In December, City Council approved selling the 17-acre site to Habitat for its appraised value ($458,300) and financing the purchase at zero percent interest. Habitat officials say the project will be a mix of single-family homes and townhouses.

“This is pretty exciting for us,” says Executive Director Andy Barnett. “This would definitely be a departure from our usual slow and steady approach.” Up till now, he notes, the nonprofit has built only single-family houses. The project’s homes will be affordable to “buyers who struggle to find decent, affordable housing on the market,” he explains.

Habitat is also considering selling part of the parcel to a partner who could develop an apartment complex with affordable rents. The nonprofit is currently “lining up funding,” and construction could begin within a year, says Barnett.

Engaging the private sector

Across the country, public/private partnerships between local governments and developers are becoming more common as a way to create affordable housing.

“I see this being done more and more,” says Jonathan Miller, co-founder of the New York City-based Miller Samuel Inc., a residential real estate appraisal company, and Miller Cicero LLC, which specializes in commercial valuation.

“By working with a developer, municipalities can enable the creation of product specific to the needs of the community over a long period of time while spreading out the risk, usually enabled by some sort of private financing,” Miller explains.

Many experts say increased private-sector involvement is essential if communities are to solve their affordable housing shortages.

Council member Smith sees the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce as a potential partner in such efforts. “It is my hope that the chamber will lead the way in modeling how a business community can effectively help to support, build and maintain affordable housing,” he says.

Last year, the chamber organized a series of meetings to explore what role, if any, the local business community could play in addressing the issue. Options discussed included public/private partnerships; encouraging large employers to help employees with housing costs; companies building employee housing; and paying higher wages. To date, however, nothing concrete has materialized from those meetings.

“We were happy that the housing bonds passed,” notes Kit Cramer, the organization’s president and CEO. “We look forward to working with the city on the specific strategies that will be used to entice developers to participate in building more affordable housing.”

One man’s plan

In the years ahead, both the bond money and the changes to the Housing Trust Fund could improve the housing prospects for tenants like Buddy Chambless. A marketing, public relations and development executive for 40 years, the West Asheville resident also believes that increased cooperation among city officials, local executives and other community leaders could help increase the supply of affordable housing while making it harder for landlords and property management companies to “milk the situation for all they can profit.”

Like Emily Coates, the photographer in Fletcher, Chambless is trying to find a better living situation. He’s even considered leaving town altogether, though the costs and inconveniences of starting over in a new place are discouraging. “But the main reason is that I feel and experience a certain positive energy from living in the valley between the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains that is deep, peaceful and serene,” says Chambless. “I really like that feeling, even with all the challenges I’ve encountered.”

And since he doesn’t expect to see “any major changes” in the local rental dynamic “in the near future,” Chambless has hatched his own plan.

“My goal is to purchase one of the longer-sized, used Airstream trailers, which can be picked up for less than $25,000,” he reveals. “With a mortgage or personal loan, payments would be less than prevailing rent payments. And in three to four years, tops, I would own my own place and never have to worry about having to move.”

LOL, rents are going up. Don’t you all get that tax increases, fees, and all the other BS ensures that?

somebody’s gotta pay back that $110 MILLION bond scam debt, so the local worker bees get to do that, since they voted in such CITY DEBT! yay, now pay!

We voted in a bond referendum for better streets and sidewalks. Now we get hit with a 40% increase in taxes because people from other places are driving up real estate values – daily. In my neighborhood sidewalks go to nowhere, the old concrete street is fine – but the asphalt on top of it is coming up.

Bravo Asheville! We are turning into Boulder, Moab, Bozeman and other places where money from other places pushes out the locals. I see more out of state plates some days than NC. I think Hunter S. Thompson’s idea for Aspen would work here too. Tear up the streets, build parking lots and rename it “Fat City”