The numbers that Andy Barnett prepared in advance of his seminar on Friday were a little grim.

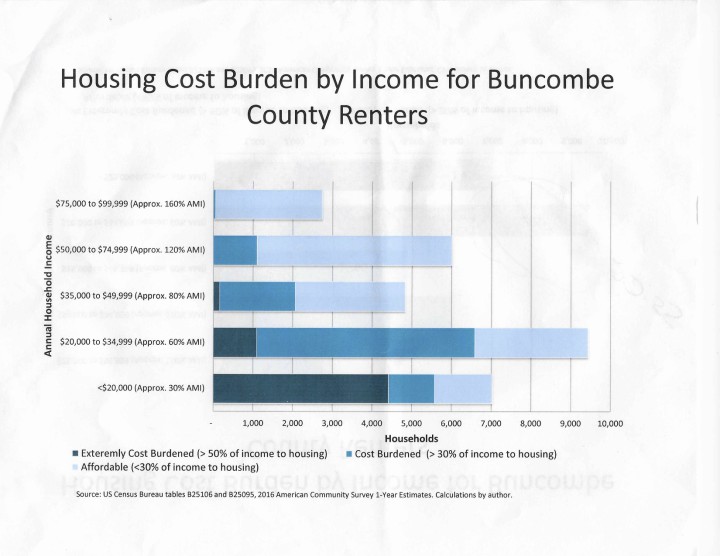

“When I made this chart, I got super depressed,” said Barnett, who is the executive director of the Asheville Area Habitat for Humanity. He was referring to a bar graph he had produced before the presentation. Most of the people in the audience were now holding copies of it. “…It came up on the screen after I monkeyed around in Excel and I looked at it and I turned the computer off and went for a walk.”

The graph depicts the percentage of annual income that households in Buncombe County spend on housing.

At the top, most households making $75,000 to $99,999 spend less than 30 percent of their income on housing, which isn’t a bad ratio.

At the bottom, most households making less than $20,000 per year spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing, which is more troubling.

Barnett was one of five speakers who presented information during one of more than a dozen seminars at an all-day housing summit held at UNC Asheville on Sept. 29.

The event was organized by Pisgah Legal Services, the city of Asheville and Buncombe County. It provided a primer for people who wanted to learn more about the area’s affordable housing problem and the mechanisms that influence attempts to address the shortage of affordable housing behind the scenes.

Solving the problem

Another chart Barnett presented detailed the approximate number of Asheville households living at different income levels, which were calculated as a percentage of the area’s median income.

Just under 7,500 households in Buncombe County make 30 percent or less of the area’s median income. Of that number, 22 percent are households of color and 95 percent live without affordable housing.

So are there any solutions? According to the members of the panel, many of the 4,000 or more households with income below $34,999 in Buncombe County have benefited from programs like public housing, housing choice vouchers and Low Income Housing Tax Credit developments.

“We have solutions that get people, even at extremely low incomes, into affordable housing,” Barnett said. “We just don’t have it at scale. … We have the treatment, we just don’t have enough doses of the treatment.”

Heather Dillashaw, Asheville’s community development director, was another member of the panel and pointed out another obstacle for the city: the fact that North Carolina is not a home-rule state. Thus, cities may not pass many kinds of local laws without the consent of the state legislature.

“What that means practically is that we cannot require developers to create affordable housing,” she said. “… The tool that makes the most impact in affordable housing, in creating actual sustainable household income across the spectrum, is called inclusionary zoning and we cannot do it.”

Dillashaw said that means the city has had to get creative.

“The legal avenues that we have to require the private market are all through the planning and zoning process,” she said.

If a developer’s plans call for features the site they’re building on doesn’t allow, they have to go through a conditional zoning process, which requires final approval by City Council.

“And City Council can ask them for whatever they want,” Dillashaw said.

Lately, Council has been asking developers for a certain percentage of affordable units in the development.

“Every single time that we have asked that and Council has stood up and voted for that, it has happened,” she said. “Because what the developer wants to do is build that building.”

Through that conditional zoning process, Dillashaw said, the city has incentivized the creation of 223 affordable units in market-rate developments over the past four years.

“223 is better than zero,” Dillashaw said.

A couple of the speakers during the presentation also addressed the importance of encouraging community involvement.

Dewana Little, who’s a member of Asheville’s Affordable Housing Advisory Committee, stressed that the issue is particularly consequential for marginalized people who have been directly impacted by the affordable housing problem.

“It’s a multi-level issue,” Little said. “It’s not just a City Council issue, it’s not a city staff issue, it’s not a county issue, it’s an all-of-us issue.”

Incentivizing developers

Under current practice, a large percentage of the responsibility for creating affordable housing rests on the shoulders of private developers.

Buncombe County recently implemented a program that encourages developers to construct affordable housing in exchange for increases in the maximum allowed density of a site, allowing developers to build more housing units and maximize the use of their land.

Jon Creighton, the planning director and assistant county manager, talked about the system during a seminar about financial and zoning incentives during the summit on Friday.

Developers get points for constructing, at minimum, a certain percentage of affordable units — and get extra points if they go beyond that minimum. They also get points for the amount of years that the housing will remain affordable, which can sunset after a predetermined period of time.

Developers also get extra points for other amenities, including handicap accessibility, street trees and the inclusion of a pool.

Dillashaw, who spoke during the same session, pointed to Asheville’s land use incentive grant program as a similar method by which the city encourages developers to build affordable housing. Like the county’s system, the city’s program also operates on a point system.

Every 10 points the developer earns equates to one year of economic incentive, which is “equivalent to city property taxes in excess of currently assessed taxes for one year annually applied,” according to an information sheet on the city’s website. Points can be earned by building a certain percentage of affordable housing, keeping housing affordable over a specified period or building near a job center.

During the Q&A section of the seminar, one of the attendees asked about some of the sunset provisions on affordable housing incentives. What happens after time runs out and those units don’t have to be affordable anymore? Will it become a problem in the future? Is the city kicking the can down the road?

“We are kicking the can down the road,” Dillashaw said. But, the city is searching for solutions. “…We’re looking for longer and longer terms of affordability.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.