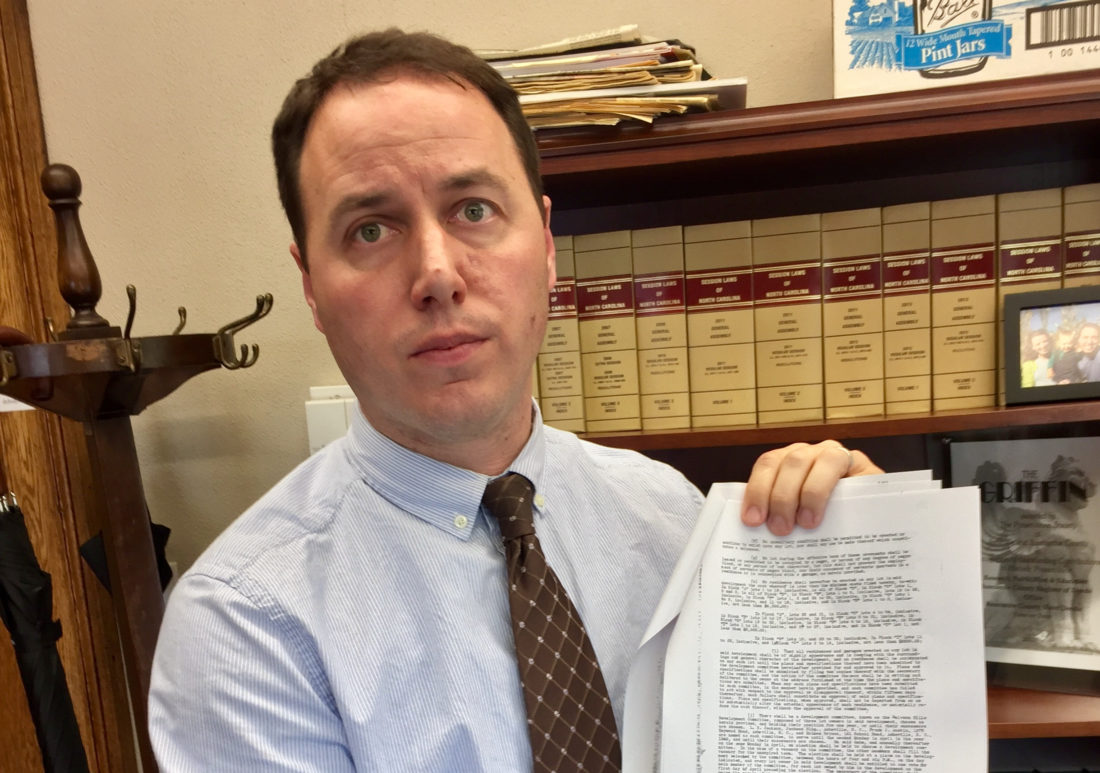

It’s rare that Drew Reisinger, Buncombe County’s register of deeds, is surprised by any historical outrages that turn up in the public records under his care. After all, it was at his direction that the county became the first one in the country to digitize its archives of deeds documenting the local ownership and sale of slaves.

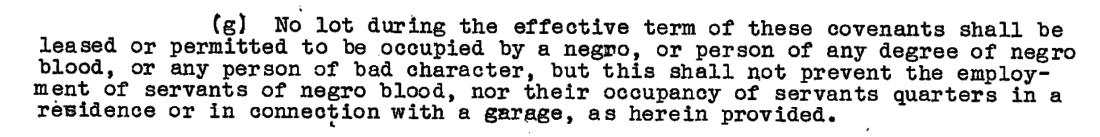

But one day in 2013, as he reviewed a title search for the home he and his wife would ultimately buy — a medium-sized rancher on Wendover Road in West Asheville’s Malvern Hills neighborhood — one of the restrictive covenants listed in the property records left him cold. Scripted in 1939 by a now-defunct homeowners association, it read: “No lot … shall be leased or permitted to be occupied by a negro, or person of any degree of negro blood, or any person of bad character.” The covenant went on to clarify that “This shall not prevent the employment of servants of negro blood, nor their occupancy of servants quarters.”

“I was shocked and saddened,” Reisinger remembers. “I can only imagine what it would have been like to find that kind of message if you were a black person thinking about joining this neighborhood, how unwelcoming and even scary that would be.”

Running with the land

Tucked into real estate deeds and other lengthy legal documents regulating property use and maintenance, aesthetic standards and the like, such racial restrictions were once prevalent in states throughout the nation. According to The Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, “Most covenants ‘run with the land’ and are legally enforceable on future buyers of the property.” Owners who violated the terms of the covenant risked forfeiting their property or, in some cases, incurring significant fines.

And though both the courts and federal housing law long ago ruled such covenants unenforceable, they remain on the books in many communities to this day. In the Malvern Hills case, a quorum of neighborhood property owners rescinded the ban on black residents in 1963 as the civil rights movement was gaining steam.

A search of old Asheville property deeds turns up many such vestiges of institutionalized racism. One that was rescinded by the Biltmore Forest Co. in 1970, for example, used almost the exact same language, banning any “negro or person of any degree of negro blood.” Likewise, a covenant in East Asheville’s Beverly Hills neighborhood, not revoked until 1983, stressed that “No persons of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building.”

And in North Asheville’s Lake View Park development, even a 1940s welcome pamphlet for property owners touted a ban on black residents, alongside details about such amenities as Beaver Lake and its boating, fishing and swimming opportunities. The development’s current website contains assorted historical documents including the pamphlet, with a note indicating that it was produced in the “pre-civil rights period.”

No one knows how many Asheville neighborhoods or properties were once subject to racial covenants, and to find out would require exhaustive research in Buncombe County’s land records.

“These things are buried all over the place,” says Reisinger. And while he’s glad to find that many neighborhoods did eventually officially renounce those restrictions, he adds, “This is a history we obviously haven’t taken a very close look at, and that’s something we need to do.”

Rooted in racism

Even before many of the local covenants were written into property deeds, Asheville was an early adopter of racial housing restrictions. In 1913, for example, the city enacted a segregation ordinance creating separate black and white residential zones. But subsequent Supreme Court cases shed light on the way both racism and legal efforts to combat it can evolve over time.

Buchanan v. Warley, a 1917 decision concerning a similar law in Louisville, Ky., declared such municipal racial zoning unconstitutional. That didn’t eliminate the underlying prejudice, however: It simply morphed into a different form.

In Asheville, for example, assorted prominent citizens endorsed a sweeping new blueprint for the city’s future in 1922. Prepared by John Nolen, a noted urban planner who also designed Lake View Park, the Asheville City Plan stated, “It is in most respects a distinct advantage to the negroes to be separated from the white population” — provided that black residents had good schools, homes, stores and recreational areas.

Reflecting such sentiments, many of the Asheville subdivisions built during the 1920s boom barred black ownership, notes local real estate attorney William Reed. “At the time, it was a clear reflection of some of those white communities’ racial beliefs and preferences,” he says. “They were unabashed about the fact that they didn’t want people of color as their neighbors.”

Accordingly, private racial restrictions — i.e., those not issued by a unit of government — proliferated nationwide. North Carolina was one of 14 states whose supreme courts upheld the legality of racial covenants when they were challenged, according to historian Richard Rothstein’s 2017 book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. And in 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Corrigan v. Buckley upheld those restrictions’ validity. Rothstein is an authority on institutionalized discrimination.

By 1948, however, the court’s position had shifted. That year, the landmark Shelley v. Kraemer ruling dealt racial covenants a theoretical deathblow, declaring them unconstitutional and unenforceable. But as Rothstein notes, the Federal Housing Administration “continued to subsidize projects that penalized sellers of homes to African Americans,” and new racially restrictive provisions still crept into legal documents pertaining to some residential associations and housing developments, even decades later.

In Asheville, other types of housing discrimination appeared after restrictive covenants lost the force of law. Some of those practices, particularly “redlining,” continued on a large scale for decades, notes local racial equity consultant Marsha Davis. She’ll recount the city’s history of redlining — the refusal by banks and insurance companies to issue loans or policies in certain neighborhoods — at a Thursday, May 30, event hosted by financial counseling nonprofit OnTrack WNC (see sidebar). Her presentation will outline various steps taken to disenfranchise, displace and corral black communities.

A lasting legacy

Today, many homeowners may not even be aware that their property was once subject to racial restrictions — and if and when they do find out, they can be flummoxed about how best to respond. In recent years, a few states, including California and Washington, have passed laws allowing individual owners to expunge discriminatory language from their deeds, but North Carolina has no such provision.

“Even when these covenants are still on record, of course, they can no longer can be invoked or enforced,” notes Reed, the real estate attorney. But that doesn’t stop some present-day owners from seeking to erase what they consider a stain on their property’s history.

Reed cites a 2009 case in which he assisted a black couple buying a house in Lake Toxaway in Transylvania County. The couple were chagrined to learn that the 1961 property deed banned “any person or persons not of the Caucasian race” (with an exception for “servants”). With Reed’s help, after buying the home, they filed a “termination of restrictive covenant” document — an addendum to the deed that, at least symbolically, renounced the racial restriction.

The document noted that both federal and state law have long banned discriminatory housing practices and spelled out the couple’s rejection of the covenant.

“You might say there’s no need for such a declaration,” Reed points out, since the restriction was already legally invalid. “But they decided that it was a concrete way to say that the values of the old owners are no longer welcome, that we have new values now.”

Whether or not old racial covenants are disavowed, they still tell an important story, argues Durham resident Stella Adams, the North Carolina NAACP’s housing chair and a veteran fair-housing advocate. During the 2000s, she studied cities where the covenants had been widely used, including Asheville, Charlotte and Wilmington.

And despite racial covenants’ lack of legal standing, Adams says their impact remains evident, even now. “In so many of these communities, you can examine the racial makeup of when the communities were built, and it’s exactly the same today,” she says.

Davis, meanwhile, believes that an examination of practices like racial covenants and redlining must inform contemporary strategies for countering deep-rooted inequalities wherever they are found.

“When we look at the achievement gap, the wealth gap, health gaps — all these stark disparities between races — it’s impossible to discuss them without taking a clear look back,” she maintains. “You can’t solve a problem without knowing where it came from in the first place.”

“Likewise, a covenant in East Asheville’s Beverly Hills neighborhood, not revoked until 1983, stressed that “No persons of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building.” Jon, are you sure it was revoked? When I moved here from Edwards AFB in California in 1999 I was shocked to see that language among the papers for my new house. I think (if memory serves me), that it was in the Beverly Hills Home Owners Association papers. I’ve asked a few times but nobody seems to know how to get rid of it. Does anybody have an update?

Hi Marcianne, good question. As I understand it, the old language can often be found in the records, even if a later revocation happens; in other words, an amendment that refers back to, but doesn’t “erase,” the prior clause, is added to the records. Hope that helps!

It is a good question. When my ex and I lived there it was still showing on record. I was flabbergasted.

Received an email today from the from the Beverly Hills Homeowners Association , whose rep who did not want to reply directly to Xpress and wanted this info to go to Beverly Hills residents only– but since I started this thread here — I thought it was relevant to anyone interested in this issue–, and the facts on the covenant wording in question should be updated. His info is clear: “We (the board) reviewed the neighborhood covenants last night and this was actually changed in 1963 NOT 1983. The wording still appears because in NC you can’t actually remove it as it’s a point of record. What it does show is a line through the stricken words and the date in which the action was taken.”

Glad to know it was updated long before I bought my house–but it still remains in the documents, though crossed out.. This is yet another argument for the NC law to be changed

I have just been informed that because I posted the above important and informative comments regarding the updated information on the Beverly Hills Homeowners covenants, which I received in a so-called private email , that I violated some unknown thing call the TOS of the digest and thus I have been “banned” i.e. excluded from the Next Door Digest for Beverly Hills and can no longer post or receive messages from the several hundred members of the digest,–a great neighborhood resource, by the way, that I used to use all the time.. I hope all the Beverly Hills neighbors appreciate the info on the covenants but know that you can’t contact me on the Neighborhood Digest . Isn’t it amazing what efforts people will go to to keep information from getting out to the larger community?

Hey Marianne, your last post sent me to look at the Terms of Service for Next Door, which says that membership can be revoked if members “repost information or Content posted on Nextdoor without the posting member’s permission.” I don’t know if that applies to your case, but I also saw that members can appeal these decisions. It’s not apparent that you have violated the TOS (but I haven’t seen the Next Door posts behind your account). Try an appeal?? And don’t be deterred from doing the right thing when it comes to exposing institutionalized discrimination.

WHOA :O That is crazy!

This is excellent information. Thank you Jon and the MtnXpress for this in depth look at our community.

Important clarification: The OnTrack WNC Financial Literacy Luncheon and Morning Seminar is NOT at our S. French Broad office in the United Way building. It is a ticketed event that is SOLD OUT. The seminar is being videoed by JMPRO TV for broadcast at a later date. Thank you!

Curious…why is the right to free association not valued? Rights (not government regulated privileges) to defense and enjoyment of life, liberty, and property were foundational to the States and nascent Republic. Granted, the question is merely rhetorical…both the Republic and the Constitution have been cold and dead for over 150 years now.

Reisinger, and every other leftist ought to really demonstrate the conviction of their principles…I demand that they (under threat of government-sanctioned force,, of course!) give everything they have have back to First Nations/Native American peoples and emigrate back to Europe or wherever the hell else they came from before invading and ruining this continent! But alas, the utter hypocrisy of the virtue signaling left knows know bounds!

That’s a high-falutin’ way to say you pine for the days of Jim Crow, and pine even more for the days when “property” included human beings.

This article doesn’t talk about rights., it talks about discrimination. It’s a right for African-Americans, or anyone for that matter to live where they want. And to not allow them to do so, as Asheville has had a history to do, goes against the very rights you say are, “foundational to the States and nascent Republic.”

Drew Reisinger’s work to expose this historic systematic racism is a step towards addressing the roots of, and hopefully changing discrimination in today’s society. It is necessary.

Also I love how you tout the atrocities committed on Native Americans only when it’s convenient to “owning” the “leftists.” How much do you defend Native American, or any other minority, rights when the conversation isn’t started by a liberal?

Your argument is weak, self serving, and hackneyed.

The Mountain Xpress has one African-American employee. One. An office assistant. The Asheville Citizen-Times has none, and neither does our local NPR station. The Buncombe County Tourism Development has no black employees and the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce has one black employee, the janitor.

Yes, Ashevegas does seem to appreciate a lack of pigment.

The percentage of Asheville’s population has been shrinking for years — about 30 years ago it was around 20%, it is now down to about 12%. A big reason for that is that all the hipsters and retirees moving here are almost all white, thus diluting the numbers. I always find it amusing when people talked about all the diversity in Asheville which, apparently, means white people with tattoos and white people without tattoos.

Another reason is that besides family ties, Asheville doesn’t give African-Americans any incentives to stay. Greensboro, Charlotte, Raleigh, Greenville SC, and Atlanta offer much more opportunities for work, community, and affordable housing than Asheville does.

Don Whitaker, What good comes from digging into our past to show our feet of clay. I don’t see any reference of our ancestors beheading or burning people alive as is being done in this day and age. As bad as the covenents were they never rose to the savagery that is being played out in the Middle East against certain groups. Let’s get beyond our past mistakes and get to the problems the exist today.

This story comes off as if the newspaper and reporter made the following decisions. 1. It is important to act surprised and good-naturedly ignorant when covering the topic of racism, because to focus instead on how racism is normalized into everything including property deeds would mean you are coming from what would actually be a surprising perspective–that of an African-American. 2. White feelings about restrictions on African-Americans are important, and African-American experiences with those restrictions are expressly not important. 3. White people feeling “in integrity” with their property deeds is important, and African-American experiences with wealth building as a result of being legally denied mortgages in certain neighborhoods (including their own and those with covenants) is expressly not important. 4. Finding one voice that says what you want in order to fulfill your decisions about 1 and 2 will be sufficient for your goals, and other voices are expressly not important. 5. Tying your message to an upcoming event will add newsiness to your story. 6. If the event features an African-American female you can feel as if you have checked the box on African-American voice and female voice.

As a newspaper and as journalists you decide what is important and you decide what and who are the sources that can share what’s important. Yes, you are gate keepers. You make these decisions every day. If you truly don’t understand that you are in control, pause and think on it. You have power and you are abusing your power. With this story you have decided that the white experience of racial injustice in America is the story that needs to be told today the city of Asheville in the county of Buncombe County in the state of North Carolina in America.

Maybe it started with your white friend. You conducted an interview. Your job is to then look for what voices are missing. Use those voices! This story sorely lacks the voice of African-American people who lived the experience. Would you agree? Ask the African-American people How did it feel then? How does it feel now? What was the impact on your life then and now? Ask the African-American people Did these covenants work to keep you out of those neighborhoods and to deny your access to the wealth building of home ownership in neighborhoods that have steadily increased in value? Ask Do you have any suggestions for what might make a difference in your life and our society today? Ask the African-American people Do we need a law to update deeds so people can feel better about their deeds in what are still predominantly white neighborhoods?

These African-American people exist. They aren’t hiding. Go into the neighborhoods that don’t have these covenants. (Because, spoiler alert, the covenants did work to keep African-Americans out, then and now.) Interview. Fact check. Use the voices. Can’t leave your office? Google and find a reputable source of information. These covenants are all over America. Interview. Fact check. Use the voices. Review your work.

Now maybe the point of view of the white person appears less important, because it is not important to this story. Maybe you’ll choose to omit the voice entirely or just use the facts that the source presented to keep your local angle. Because you get to decide what’s important and who gets to have a voice. You are the gate keepers.

Or maybe the story started with the upcoming talk on redlining and you looked for a white friend who has feelings about the general subject? Doesn’t matter. Journalism is work. Do the work. You are going to publish something every week. Why not make it good?

“And in North Asheville’s Lake View Park development, even a 1940s welcome pamphlet for property owners touted a ban on black residents, alongside details about such amenities as Beaver Lake and its boating, fishing and swimming opportunities. The development’s current website contains assorted historical documents including the pamphlet, with a note indicating that it was produced in the ‘pre-civil rights period.'”

Maybe they still have it in their website as a warning to black people that even though it’s not legally enforceable, they want black people to know they still aren’t welcome to the neighborhood.

Hmmm… my how have times changed! (Not really) Penalties laws and fines to keep African Americans out of certain communities and now the black neighborhoods are being gentrified! SMH!