On Dec. 5, three members of the Transylvania County Board of Commissioners took a leap into the unknown. Chair Mike Hawkins, Vice Chair David Guice and Commissioner Page Lemel announced that they would be leaving the Republican Party — not to become Democrats, but to renounce party affiliation altogether.

“Our focus is local, our objective is problem-solving for Transylvania County and our experience is that partisanship is an obstacle to effective local governance,” the trio wrote in a press release regarding the move. “Governing is done best when done closest, and close governing is done best when removed from partisan encumbrances.”

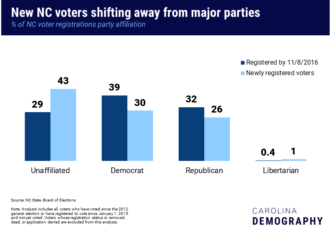

The commissioners’ decision aligns them with the more than 2.23 million voters across North Carolina currently registered as unaffiliated. That number makes unaffiliateds the state’s second-most populous political group, trailing only Democrats, and the gap is closing: Since 2016, according to the University of North Carolina’s Carolina Population Center, 43% of all new voter registrations statewide have been unaffiliated, compared to 30% Democrat and 26% Republican.

Despite this uptick in voters who claim no formal allegiance to a political party, elected officials who share their position are few and far between. No members of North Carolina’s congressional delegation are unaffiliated, nor are any officeholders at the state level. According to the N.C. Association of County Commissioners, just seven of 587 total county commission seats were won by independent or third-party candidates in 2018.

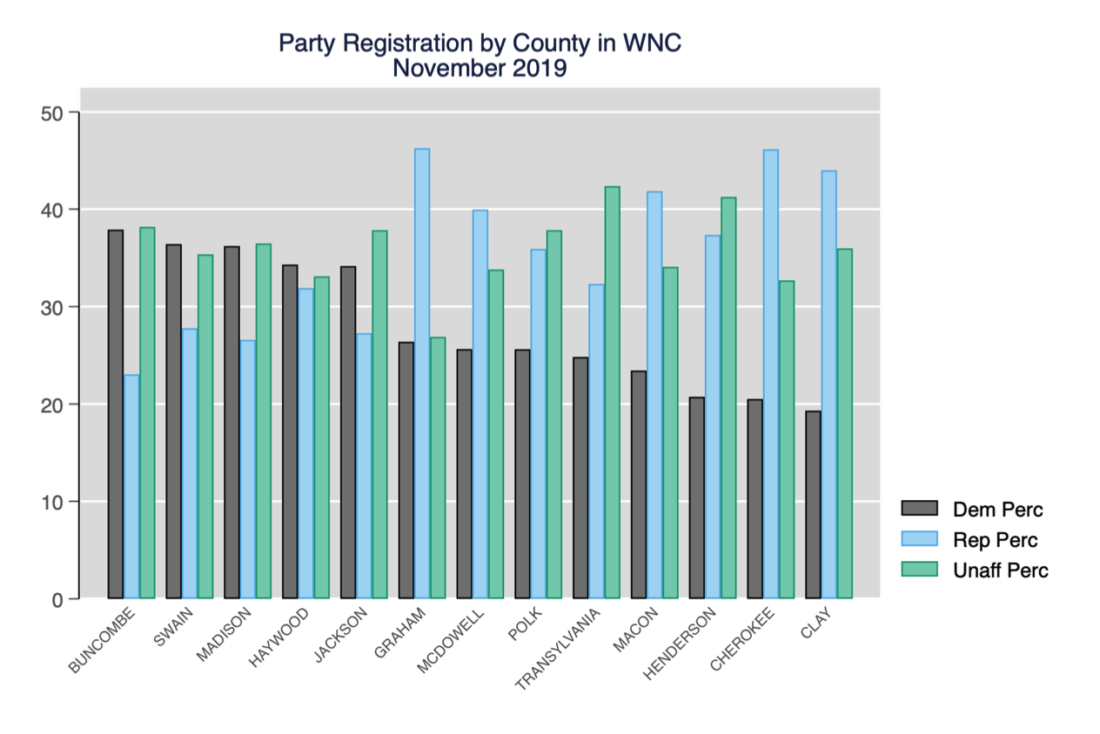

“Unaffiliated officeholders are kind of a long-endangered species: We know they exist, but they’re sort of hard to find,” says Chris Cooper, head of Western Carolina University’s Political Science and Public Affairs Department. “By 2022, unaffiliateds will be the largest group in North Carolina if the current trends continue. Yet the number of unaffiliated officeholders you can count on a couple hands.”

Contributing to what Cooper calls an “interesting mismatch” are the state’s rules for unaffiliated candidates. Unlike partisan candidates, those running as unaffiliated must gather signatures from registered voters in the area they hope to represent to appear on the ballot; most offices require 4% of voters in a district to sign a petition, which often equates to many thousands of names. And the state’s deadline for gathering those signatures — noon on primary election day, Tuesday, March 3 — is the nation’s earliest by more than two months.

As that deadline rapidly approaches, Xpress spoke with political experts and several of Western North Carolina’s unaffiliated hopefuls to better understand the landscape outside the two-party system.

Why the rise?

Cooper points to several reasons for the increasing popularity of unaffiliated voter registration. The first is tactical: In North Carolina, those enrolled in a party must vote in that party’s primary, while unaffiliated voters can pick from among all of the partisan ballots. “You get to choose your own adventure,” he says.

Demographic changes are also shifting the state’s political realities. Young professionals who migrate from outside of North Carolina to rapidly growing metro areas such as Asheville and Charlotte, Cooper says, are less likely to be attached to a party than are older residents.

Finally, Cooper flags heightened partisan rhetoric on the national stage as a major disincentive for voters to express an affiliation. “There’s almost a social sanction at this point, the country’s so polarized,” he says. While some people may still hold partisan beliefs, he continues, “they just want to hide [those beliefs] from their friends, their colleagues, their co-workers.”

Politicians likewise have a variety of rationales for rejecting parties. Winn Sams, a Columbus-based chiropractor running for U.S. House District 11, wants voters to focus on the merits of individual candidates instead of partisan slates.

“It represents what I’m trying to bring, which is a change where we’re not looking at voting a party in, but a person in,” Sams says. “What if the person isn’t very good? What if the person isn’t very honest, but yet they represent your party? Are you really getting representation?”

In Transylvania County, Lemel says her departure from the Republicans was a matter of ideological hardening. While the party previously had a place for her fiscally conservative, socially moderate viewpoint and spirit of cooperation, she explains, an “all-or-nothing way of functioning” has replaced that tolerance in recent years.

“We’ve lost the ability to have civil discourse,” Lemel continues. “We’ve been lowered to name calling and character assassinations that are wholly inappropriate when dealing with other human beings.”

And Andrew Celwyn, an unaffiliated candidate for the chair of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, says he wants to bring attention to the electoral process. While he’d previously planned to compete in the Democratic primary against incumbent Brownie Newman, state law prevented him from doing so because he had switched his affiliation from unaffiliated to Democrat fewer than 90 days before the filing deadline.

“Collecting signatures will help our campaign have conversations about the different barriers to participating in our democracy,” Celwyn wrote in a statement on the Asheville Politics Facebook group. “Whether discussing voter ID, the influence of money in politics or changes in our laws that make it harder to participate, we will embrace the opportunity to better connect with voters on this issue.”

Early alarm

Those barriers, says Richard Winger, are particularly high in North Carolina. The California-based political analyst publishes and edits Ballot Access News, a monthly newsletter that tracks rules for third-party and independent candidates across the U.S.

A 2017 state law passed almost entirely by Republicans over the veto of Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper moved the deadline for unaffiliated candidates to submit ballot petitions from the last Friday in June before the general election to the second Wednesday prior to the primary election. The date was moved later that year to the primary election itself on March 3.

The March deadline, Winger points out, is more than two months before the country’s second-earliest cutoff, set by Texas as Monday, May 11. North Carolina’s deadline was challenged in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina in 2019, but Chief Judge Terrence Boyle, an appointee of Republican President Ronald Reagan, dismissed the case on Nov. 22.

“The U.S. District Court judge who upheld that early March deadline is the least competent federal judge I have ever seen,” Winger says. “There are about 55 federal court decisions saying that early deadlines are unconstitutional, including a published decision in 1980 in North Carolina, Greaves v. N.C. Board of Elections, which struck down April as too early. Our current case judge didn’t even mention that decision.”

Boyle did not respond to an Xpress request for comment by press time. Neither did Republican Reps. Dana Bumgardner and Jason Saine, two primary sponsors of the law that first moved North Carolina’s deadline; both are still serving in the General Assembly. The bill’s other sponsors were Republican Rep. Cody Henson, who resigned in July after pleading guilty to cyberstalking his estranged wife, and Republican Rep. Justin Burr, who lost his primary election in 2018.

Beyond the tight deadline, unaffiliated candidates in this election cycle have had to wrestle with the additional uncertainty brought on by North Carolina’s redistricting at both the state and federal levels. Those shifting boundaries, Sams says, meant she had to change her candidacy from District 10 to District 11 and still must gather roughly 7,750 signatures.

“With the congressional district lines being redrawn — everything I’ve done up until this point, most of it doesn’t count,” Sams says. Of the eight counties she’d previously canvassed, she adds, “The only signatures that would count right now are in Polk [County] and a little bit of Rutherford [County] with Lake Lure.”

Sign them up

Asked for his advice to unaffiliated candidates given these challenges, Chris Cooper responds, “Find a new strategy and register with a party, and I mean that. The barriers are so large.”

Nevertheless, several WNC candidates remain committed to their unaffiliated runs. In Buncombe County, Celwyn says he will set up shop at political events, visit malls and host town halls to gather the 9,000 signatures required for his ballot petition. Door-to-door canvassing is also on the table to drum up the needed support.

“It is a challenge,” Celwyn admits. “I’m not making light of it or short shrift of it, but it’s something I think I — and hopefully people who are supporting me — are up to.”

Given the largely rural character of the area she hopes to represent, which stretches from Avery County in the northeast to the state’s southwestern tip in Cherokee County, Sams says she’s relied on businesses in District 11’s population centers to host her petitions. In Henderson County, for example, voters can sign their support while picking up medication at Economy Drugs in Hendersonville.

“Honestly, I don’t know if I can do it,” Sams says about meeting the petition target. “One of the issues that I have in getting signatures is that it requires people to get out and sign the petition. You can’t sign it online and you have to be a registered voter of the county you’re signing the petition in.”

Even Celwyn says he expects issues with obtaining signatures on paper from supporters in Buncombe County outside Asheville’s urban core; he would like to see the state Board of Elections allow an electronic petition system. “I know that’s kind of a pie-in-the-sky desire in some ways but I think that would be in keeping with the times,” he says.

Yet if these unaffiliated candidates succeed in their petition drives, Cooper points out, they’ll still be at a disadvantage compared to their partisan rivals in the key arena of campaign financing. Republican and Democratic primary winners, he says, gain access to party donor lists and supporter contacts.

“If you’re running as an unaffiliated candidate, you have to build all those lists from scratch,” Cooper says. “That kind of background research that the parties do and the in-kind donations that you get as a member of a party are worth a lot of money.”

Making change

Perhaps with those obstacles in mind, none of the newly unaffiliated Transylvania County commissioners have yet committed to a reelection campaign. Guice, who will hold his seat through 2022, did not respond to an Xpress request for comment, while both Lemel and Hawkins, whose terms expire in 2020, say they are not currently circulating petitions.

However, Hawkins is interested in expanding ballot access for unaffiliated candidates in the future. He acknowledges that such an effort could be an uphill battle — “It’s unlikely that politicians within an established party structure would be keen on facilitating processes which might threaten that structure,” he says — but that he’d like “to work with like-minded people” to make improvements.

As a first step, Hawkins suggests restoring the Transylvania County Board of Education to a nonpartisan entity. Former Republican Rep. Chris Whitmire, he says, sponsored a bill in 2016 that shifted the board to partisan elections “over the unanimous objection” of existing members.

Lemel agrees with her colleague that local races, including those for county commission, should be run on a nonpartisan basis. While parties may make sense to coordinate action at state or national levels, she says, partisan politics “distract from the conversation” in cities and counties.

“What role does being a registered Democrat or registered Republican have to do with enforcing the law as sheriff?” Lemel asks. “What role does being a Democrat or a Republican play in the Register of Deeds office?”

But without alterations to the way elections are conducted, Cooper suggests, two-party representation will remain the norm for the foreseeable future. And both Democrats and Republicans in the state legislature, he adds, are in no hurry to change.

“The parties are still the ones who are controlling the system, so it stands to reason that the folks elected by a party aren’t going to fight against that party,” Cooper says. “If anything, it’s the opposite: Both parties seem to want to, not surprisingly, support the two-party system.”

I live in Guilford County, not in WNC, but I came across this article and just had to leave a comment: Well done, sir, well done. This piece is interesting, informative, and so well written. You are a credit to your profession.

Under the current primary system, unaffiliated and third-party candidates have nearly zero chance of success. This could be addressed by 1) adopting an open primary system like California where all candidates from all parties compete in a single primary open to all voters and 2) changing to approval voting where you check a box beside all the candidates you find acceptable (winner is the one with the most approvals). Those changes would also go a long way toward breaking the R/D stranglehold on our politics.