Given even a relatively brief time in Asheville, visitors and residents alike can gain a sense of the city’s historical significance in art, music, food, beer and forestry. But this midsize mountain enclave also had an outsized influence in the Civil Rights Movement and a thriving Black community that is rarely celebrated.

Thanks to a $500,000 grant from the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority and years of collaborative work between Explore Asheville staff and the River Front Development Group, those neglected stories are now being told via 14 kiosks between Asheville City Hall and the French Broad River.

The Black Cultural Heritage Trail celebrates the accomplishments and contributions of Asheville’s Black community dating to 1865, when the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution formally abolished slavery in America.

“It’s not a mystery why local Blacks are not celebrated, their achievements promoted or even discussed,” says Catherine Mitchell, executive director of the River Front Development Group and one of the primary organizers of the project.

“That’s one of the reasons that you have a trail that begins to tell the story of the community, its development and its successes, and then you have a museum where kids can begin to appreciate the success of their relatives,” she adds.

Work on a museum is underway at Stephens-Lee Community Center on the site of the former all-Black high school of the same name, funded by a different $100,000 grant from the TDA.

From Asheville’s first elected Black person in 1882 to the destructive outcomes of one of the South’s largest urban renewal projects in the 1960s and ’70s on a previously thriving Southside community, the milelong trail takes visitors through the undertold stories of Black Asheville’s long history in three sections.

Origin story

Origins of the trail trace back to 2010, when residents of the historically Black East End neighborhood proposed the idea to Mitchell and Marcell Proctor, president of the River Front Development Group, which took on execution of the project and began looking for funding.

There aren’t many organizations willing to fund a trail and Black history museum, says Mitchell. But when she eventually met with a representative from Explore Asheville, they loved the idea.

“It blew my mind,” she says with a laugh. “They’re right in town!”

A grant was first awarded in 2018, and a project team was formed to conduct listening sessions and community engagement from 2019 through 2021, when an 18-member advisory committee was formed to help guide the trail’s design, themes, route and featured content. Finally, the trail launched in December 2023.

Mitchell says the committee had specific goals that went beyond retelling history. They wanted to focus on the stories worthy of celebrating in Asheville’s Black history, partly to help the younger generation understand that their ancestors could not solely be defined by slavery.

Kimberly Puryear, destination project manager at Explore Asheville, says the committee worked to highlight the agency and resiliency evident in Asheville’s Black history on the trail.

“So often the focus is slavery, and then it jumps straight to civil rights,” she says. “There’s all these other local stories. So we really wanted to lift up local voices that represented these threads that are running throughout national history as well.”

Each kiosk on the trail ties local events to what was happening nationally at the time, putting everything in context, she adds.

Four goals arose from the 2019 listening sessions and community workshops that wound up guiding the overall project. The trail aims to celebrate the “accomplishments and contributions of the Black community in Asheville, individuals and groups that supported the community and Black people’s agency and the capacity to express individual power.” Designers also hope to “combat or correct misconceptions and preserve history for future generations,” according to the project’s official goals.

The trail’s logo, a mythical sankofa bird, refers to an indigenous Ghanian word that roughly translates to “go back and get it,” according to the trail’s website. That message is echoed in the guiding message of the River Front Development Group: “We should reach back and gather the best of what our past has to teach us so that we can achieve our full potential as we move forward.”

Mitchell hopes younger generations of Ashevilleans will take that message to heart and that the trail will help inspire them to seek a deeper understanding of what it means to be Black in Asheville.

On a recent tour of the trail with Puryear and fellow organizer Dr. Joseph Fox, Xpress heard dozens of stories that redefined a vision of what life in Asheville was like in the decades following the Civil War. What follows are just a few highlights.

Downtown

Fittingly, the tour starts in front of the Buncombe County Courthouse and Asheville City Hall with a story about Asheville’s first Black elected official, Newton Shepard. Shepard was elected to a 12-month term as an Asheville alderman in 1882 and re-elected in 1883. It wasn’t until 1969 that another Black man, Ruben Dailey, was elected to City Council.

Elsewhere on the downtown section of the trail, plaques commemorate the significance of the all-Black Allen School for girls — attended by such luminaries as Nina Simone and Christine Darden — and Stephens-Lee High School, both located in the East End neighborhood across Charlotte Street.

Students from both schools helped establish the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality (ASCORE), which helped integrate Asheville through sit-ins and petitions. The high schoolers distinguished themselves at a time when sit-ins in places like Greensboro were led by college-age protesters.

A kiosk notes that among other achievements, ASCORE’s Viola Spells and Oralene Simmons, who participated in many Civil Rights Era protests and went on to found the Martin Luther King Jr. Prayer Breakfast, helped desegregate a public library in 1961.

As the trail winds south toward the historically Black commercial district known as The Block, Fox points out that here, unlike on the rest of the trail, many of the Black-built buildings remain.

Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church on the corner of Spruce and Eagle streets — built by master brickmason and former slave James Vestor Miller — represents the importance of Black churches as community gathering spaces and supports.

On Market Street, the Young Men’s Institute, now the YMI Cultural Center, stands as one of the oldest Black cultural centers in the United States, a living testament to its importance as a cultural hub in the fight for equal rights. Across the street from the YMI, the W.E. Roland Jewelry Co. served as a resource and meeting space for ASCORE, and owners William Ernest Roland and Georgia Evelyn Harling helped the group protect voting rights and advocate for equal opportunities.

Farther south, a kiosk celebrates former slave Isaac Dickson for his sprawling real estate investments in a nearby area known as Dicksontown, one of many success stories of freedmen-turned-businessmen in Asheville.

“Really, throughout the South in Black communities, you had two or three Black leaders that created self-sustaining communities,” Fox says. “In your local communities, you had your churches, you had your grocery stores, you had your barbershops and your hair salon.”

Such local support systems were vital, because in the white neighborhoods in between these enclaves, Black people weren’t welcome, Puryear notes.

Southside

On any given Saturday in what is now referred to as the South Slope, passersby will observe hundreds of white brewery hoppers downing pints of craft beer. The streets are lined with drinking establishments and music venues in a quintessential example of gentrification.

Just decades ago, thousands of Black folks gathered in the same area on weekends to watch baseball games, gather with Black families from across the mountains or get their car fixed by Black-owned mechanic shops.

Back then, this area, stretching from Hilliard Avenue south to Oakland Avenue, and including areas between Biltmore Avenue and the French Broad River, was known as Southside.

The trail’s four stops along Buxton and Coxe avenues tell pieces of what the Southside community used to be while acknowledging the toll urban renewal had on the area.

One plaque celebrates the role Black people had in helping treat tuberculosis patients who flocked to Asheville’s clean mountain air in the late 1800s. Asheville was home to America’s first Black pulmonologist, Dr. John Wakefield Walker, who opened a sanatorium in 1915.

Another kiosk celebrates the entrepreneurship of Edward Walton Pearson, who developed a subdivision in the present-day Burton Street neighborhood, founded the Buncombe County Colored Agricultural Fair, built a park in present-day South Slope and formed Asheville’s first Black semiprofessional baseball team in the 1910s.

Once urban renewal displaced half the city’s Black population in the 1970s, Pearson’s wife, Annis Bradshaw Pearson, co-founded multiple clubs to help serve that population.

After passage of the National Housing Act of 1934, the Southside neighborhood was the target of one of the region’s largest urban renewal projects, the East Riverside Urban Renewal Project. Homes were demolished, roads were rerouted, and residents were moved into public housing, destroying not just neighborhoods but generations of wealth, Fox notes.

A map credited to Betsy Murray, an archivist at Pack Memorial Library, shows the locations of 30 churches, schools, community organizations and businesses that existed throughout Southside before being destroyed by urban renewal. Similarly, there were 28 such institutions in the East End neighborhood and 19 more in Stumptown and Hill Street in present-day Montford.

Once the Black community was priced out of their homes or lost property to eminent domain, the already existing wealth gap was greatly expanded, Fox says.

River area

Closer to the river, in what is now referred to as the River Arts District, the trail starts near Black Wall Street AVL, one of the cornerstone organizations uplifting Black-owned businesses in the region.

Standing on the corner of Lyman Street and River Arts Place, a kiosk commemorates the successes of Asheville native Matthew Bacoate Jr., who operated the first Black-owned manufacturing company in Western North Carolina in the 1960s and ’70s, manufacturing personal protective equipment. Before his success led him to counsel Presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter on Black entrepreneurship, he helped integrate an Asheville bowling alley and the Asheville Municipal Golf Course.

As Fox tells it, Bacoate, who worked at an all-white bowling alley, started to sneak his Black friends in after hours on Sundays to bowl. Some of the white bowlers found out and wanted to bowl on Sundays as well, not caring that there were Black bowlers there. Eventually, the alley became fully integrated as it became clear that everyone just wanted to bowl, Fox says.

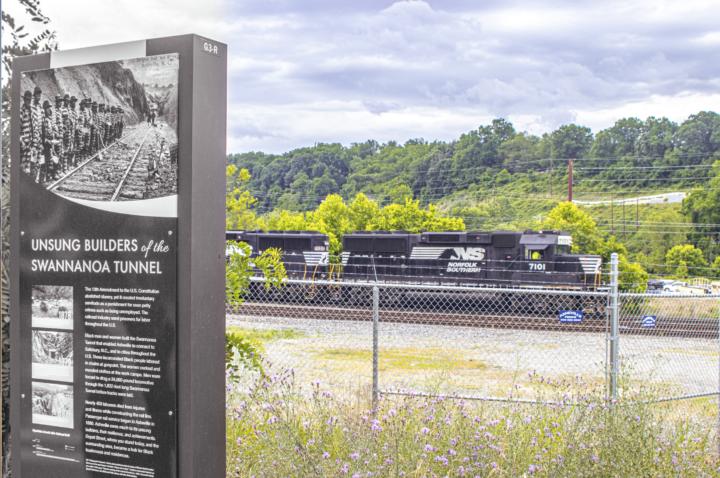

A plaque on Depot Street facing an active railroad line recognizes the brutal involuntary servitude that Black prisoners endured, in chains and at gunpoint, building the Swannanoa Tunnel for the railroad industry in the 1870s.

Decades later, Black rail workers who worked in trains traversing that very tunnel formed a union to fight for their rights — the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids. Black railroad workers were civic leaders who invested their wages in the Southside community.

Another plaque in the river area tells a story that resonates with that of civil rights icon Rosa Parks. In 1951, four years before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 75-year-old William “Seabron” Saxon refused to give up his seat on a bus bound for Asheville from Atlanta. Police forced him to move, and his resulting lawsuit against the bus company, while unsuccessful, helped spotlight discrimination in public transportation.

The trail ends near Green’s Mini Mart on Depot Street, one of the few holdovers of Black businesses on a street full of new development. At the end of the tour, Fox, who is from Tryon, reflects on his own family’s visits to Southside’s once-thriving Black community for baseball games, picnics and Black-owned shops.

As longtime Black activist and Buncombe County Commissioner Al Whitesides has said on numerous occasions, people new to town often ask, “Where are the Black people?” As the Black Cultural Heritage Trail documents, step by step and memory by memory, they’ve been here all along.

For more information and a virtual tour of the trail, go to avl.mx/dtd.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.