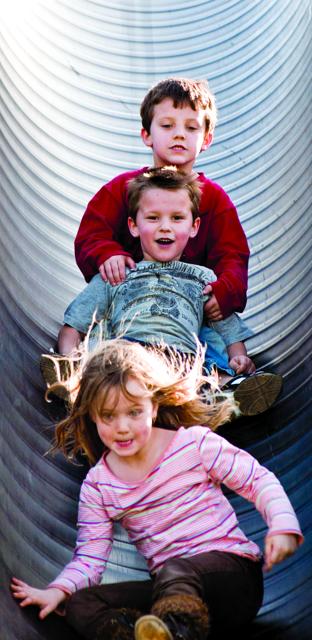

- Shoots and leaders: Eliada Homes’ after-school programs use the Golden Rule to help kids learn to relate to one another. Photo by Max Cooper

- Use your bean: At Ira B. Jones School, kids use the “defender bucket” as a tangible reminder to be kind to one another. Photo by Max Cooper

- No bullies on board: This Ira B. Jones Elementary bus has been recognized by the school for its peaceable atmosphere. Photo by Max Cooper

An unusual bit of bean counting took place at Ira B. Jones Elementary School in north Asheville. During a school assembly — part of national “No Name-Calling Week” — students and staff were encouraged to pluck a bean out of a jar for every time they’d ever felt bullied or were the target of unkind words. They dropped the beans in a “defender bucket,” recounts Assistant Principal Ted Duncan, and about 400 beans were collected in all. Now, whenever a teacher or student sees a student defending someone else, they take a bully bean out and throw it away.

“Doing that gives the students a tangible reminder throughout the day, throughout the months, [that] we want you kids to be kind to each other and we’re tracking it,” Duncan explains. “We want all students at school being safe, both physically and emotionally.”

Although the defender bucket is a novel example, it seems that schools have gotten serious about bullying. Bullying has typically been considered an inevitable rite of passage through the landscape of childhood and adolescence.

But times have changed. State laws across the country have put the onus on schools to address bullying — whether it happens at school or the night before in a nasty Facebook post. School administrators and teachers are taught how to recognize bullying and stop it. Kids are schooled in the dynamics of bullying and what they can do when they encounter it.

Power and control

To understand how schools handle bullying, it’s important to understand how it is defined. “Bullying is when someone repeatedly and on purpose says or does mean or hurtful things to another person who has a hard time defending his or herself,” says Michele Lemell, safe-schools and healthful-living coordinator for Asheville City Schools.

That could include pushing and shoving on the playground in elementary school, name-calling, purposely excluding others in middle school and, in the early teen years, social and emotional abuse, possibly through electronic means and social media, says Lemell. Trend data show that bullying slowly increases from elementary to middle school, then tapers off in high school as kids become more adept at shaking off insults.

David Thompson, director of student services for Buncombe County Schools, points out that the bully’s intent is to intimidate and to “have some kind of power or control” over the victim. That distinction also helps adults differentiate bullying from other types of misbehavior, he says.

But bullying isn’t only about the bully and the victim. According to Deborah Miles, executive director of the Center for Diversity Education, there are four participants in the “power continuum”: the bully, the victim, the bystander and — every now and then — the advocate.

A key part of turning a bullying situation around is converting bystanders into advocates, Miles says. In fact, research indicates that changing bystanders’ behavior has the biggest impact on reducing bullying.

”It should not just be the struggle of the child who is the target,” she declares.

Bullying doesn’t just affect the few, either. Thirty-two percent of students ages 12-18 reported being affected by bullying, according to 2007 figures from the U.S. Department of Justice.

Schools have a vested interest in preventing and addressing the problem: “Bullying distracts from a learning environment,” Miles observes.

Stopping bullying before it starts

Both Buncombe County and Asheville City schools use an approach known as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, which promotes safe and respectful behavior at school. According to the PBIS website, behavioral expectations are taught in the same manner as any other core-curriculum subject.

In the classroom, teachers post a list of the positive behavior they want — usually revolving around respect, responsibility and safety — along with rules on what not to do, Thompson says. Teachers monitor the students and reinforce proper behavior. “And then if they make mistakes, then we re-teach just like if we were teaching them math,” Thompson says.

The school system embarked on the program about five years ago; by the end of this school year, 19 of Buncombe County’s 42 schools will be trained in PBIS, Thompson says. Eight schools per year will come online until all the schools have received training, he says.

More recently, as directed by the 2009 School Violence Prevention Act, Buncombe County Schools has trained its staff to recognize bullying, then report, investigate and intervene. “I think the most challenging part is training staff well enough to recognize it when it’s happening,” Thompson says.

Depending on the situation, school officials might work separately with the bully and the victim on strategies to keep problems from happening again. It may include discipline, but discipline alone usually doesn’t stop bullying, Thompson says: “If discipline stopped bullying, we wouldn’t have any.”

When a child’s safety is involved, the schools might use assigned seats on a bus, or change a child’s schedule to head off opportunities for bullying. In some cases, the bully might be reassigned to another school in the district.

When it comes to cyberbullying, the new law allows the schools to address bullying that might start off campus if it creates a serious disturbance in the school environment, Thompson says.

Buncombe County Schools also provides ways for someone to anonymously report bullying, both through an online form on the system’s website (http://www.buncombe.k12.nc.us) and through an Anti-Bullying Hotline (225-5292).

Be the change

Along with encouraging positive behavior, Asheville City Schools has embarked on another program that boasts a reduction in student reports of bullying by 30 to 70 percent.

The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program was launched in Norway after three adolescent boys there committed suicide in 1983, most likely due to severe bullying by peers.

The program seeks to involve all students and adults in the school community, including teachers, bus drivers, custodial staff and parents. Its goal is to change the climate at schools so that bullying isn’t seen as cool and that no child is marginalized. Olweus includes student surveys on bullying and classroom meetings to teach anti-bullying strategies.

While Miles calls the Olweus program one of the best, she acknowledges that training expenses can be a stumbling block for school systems. The program has four rules about bullying (three of which focus on the all-important bystanders): We will not bully others; we will try to help students who are bullied; we will try to include students who are left out; if we know that somebody is being bullied, we will tell an adult at school and an adult at home.

The Olweus program started in the system’s elementary schools about a year ago, while Asheville Middle School is in the beginning stages. Asheville High and the School of Inquiry and Life Sciences (on the Asheville High campus) will follow in the fall.

Though the program is still in its infancy, “I think we’re starting to see those first initial changes in behavior,” Lemell says.

”They are never alone”

As Arden mom Laura Hope-Gill has found, bullying can take on various, subtle forms that can be hard for adults to detect.

Hope-Gill found out almost by accident that her daughter, 8-year-old Andaluna Malki, was being bullied at Glen Arden Elementary School. One day, Andaluna told her mom that she had to bring two snacks to school. When asked why, Andaluna explained that she hadn’t done enough jumping jacks the day before. Probing further, Hope-Gill discovered that another girl was bullying not only her daughter, but others as well.

Andaluna felt strongly enough about the situation to write an essay about it, called Be Strong: An Idea How to Handle Bullies.

“I have a bully at my school,” Andaluna wrote. “She is in my grade. These are the things that she does: she calls people names. She makes people cry. She tells people what to do, and she gives people punishments: You have to do 20 jumping jacks. You have to hug her every day. She makes children feel mad and sad. I have an idea that can help …

“I think it would be a good idea to have little tables at a school where children could sit and listen to other children who are being bullied. … It would be children helping children. … My idea tells children they are never alone.”

Hope-Gill got positive feedback about Andaluna’s essay from the school’s principal and guidance counselor, adding, “I was really pleased that the idea got passed around.”

It’s important, Hope-Gill says, to allow for enough unstructured time for a child to open up about what’s going in her life. “I don’t know any parent who can sit down and ask a direct question and get the direct answer,” Hope-Gill says.

And the sooner parents can let school officials know about a bullying problem, the better. “Please don’t wait months and months and months to tell us,” urges Lemell.

“If it goes unreported, it’s very difficult to stop,” adds Duncan, the Jones Elementary School assistant principal.

The wide world

Eliada Homes, which offers after-school care for about 75 students from six Buncombe County schools, launched its own anti-bullying program a year ago to resolve problems they were having, says Ashley Trimnal, Eliada’s program coordinator for school-age services.

“There was a lot of taunting and a constant back-and-forth battle between the kids and groups of kids,” Trimnal explains. The program gives kids tips on how to handle their emotions and directs them to follow the Golden Rule — all in an atmosphere of building self-esteem and working together as a team. “They are finding slowly but surely that working together is much easier than working against each other,” Trimnal says.

And it’s not just school officials and program coordinators who bear the responsibility of preventing and stopping bullying. Young people respond to what all of the adults in their lives set as the norm, says Miles of the Center for Diversity Education.

“All of us adults need to be on the same page of creating that respectful culture and … model that,” she says.

— Tracy Rose is an Asheville mom, writer and editor.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.