Photos by George Etheredge

Up a curvy country road in Candler sits a farm filled with open pastures and long fences, framed on all sides by scenic mountain ridges. Bitter February winds cut through the warmth of a late winter sun as a young farmer looks over rows of raised beds that will soon hold lettuce, corn, squash and more. In the coming months, the farmer will create compost that will strengthen the soil, pull weeds from among the vegetables and plant trees that will grow into a fruit orchard. The farmer will lead a Community Supported Agriculture program and sell produce at local markets. In fact, this farmer will do everything you’d expect a farmer to do — except look like the farmer you’d expect to see.

Calixta Killander became interested in agriculture when she was 19. Now, at age 25, she serves as the garden manager at The Farm (as the property is aptly called), having moved to Asheville from her native Yorkshire, England, to study sustainable agriculture at Warren Wilson College.

Killander discovered her passion for growing food while traveling in India and seeing how essential farming was to impoverished communities. During those travels, she noticed something surprising about India’s farmers — most of them were women.

“They were out there in their beautiful saris, with their amazing jewelry and jasmine flowers in their hair, and they were doing this hard, physical work,” Killander recalls. “It was this striking juxtaposition between the beauty of females and also how strong, powerful and resilient they were. They were the ones with babies on their backs, taking care of the children and doing that hard work — and the men weren’t.”

That’s a sharp contrast to the classic picture of the American farmer. From the rancher with the cowboy hat and lasso to the grower on the tractor gazing out over the cornfield, our idea of a farmer is most often of a male — specifically an older, white male. In many ways, statistically speaking, that image isn’t wrong — but it may be changing.

According to data from the 2012 U.S. Census of Agriculture, released in February 2014, farmers in America are overwhelmingly Caucasian and male. Of the 2,109,303 farms surveyed, 2,034,439 had a principal operator who was white. Only 288,264 of the chief operators were women.

But the American farmer is aging: Between the 2007 and 2012 censuses, the average age of principal farm operators rose from 57.1 to 58.3. In a profession that demands physical labor and long hours, often coupled with harsh economic realities, that means many may soon be retiring. In fact, the total number of U.S. farmers shrunk by about 3 percent in the new census.

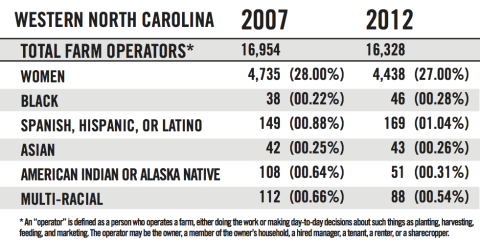

Nationally, the numbers show, new farmers aren’t rushing to enter the field. But according to an analysis of the census data by Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project, Western North Carolina actually showed gains in total regional farmland and in another surprising area — minority farmers. The number of black, Hispanic and Asian farmers in WNC rose, while the number of women farmers declined slightly but held roughly the same total percentage.

Both nationally and regionally, women and minorities still account for only a small percentage of our farmers. But “Learning and working with the land is something anyone can do, and it’s something that no one should be separated from,” Killander asserts, and it seems she is not alone. So who are these new farmers? What challenges are they facing? And as diversity in farming grows, what new perspectives will they bring to agriculture in WNC?

The lady farmer

Black Mountain resident Becki Janes writes poetry and dances the tango — two facts that, on their own, are not particularly surprising. But Janes is also a farmer, something she says many people can’t seem to reconcile with her more feminine pursuits.

“They’ll see me in a dress, and they’re just totally shocked,” Janes say. “Being a farmer does not equate with the loss of femininity. And yet, it’s like people look at me and think, ‘You’re not supposed to look like that!’”

Janes owns Becki’s Bounty, a 1/10-acre farm near downtown Black Mountain. Though she studied both veterinary sciences and agriculture in college, her farm is actually a pretty recent development in her life. After her undergraduate studies, Janes switched her focus to counseling, completed a master’s in the field and embarked on a decadeslong career in child and family services. Five years ago, she was serving as executive director of a local nonprofit and wasn’t considering a career change — until she suffered a heart attack.

Today Janes is healthy and preparing to run a half-marathon; and her farm, which she started as part of her recuperation, is the new driver in her life. “People have heart attacks for a lot of different reasons, but I know for me, a big part of it was stress, in my work and in my life,” she says. “This 180-degree turn on my career — the garden — has saved my life in a lot of ways.”

At Becki’s Bounty, Janes uses sustainable practices to grow organic produce that she sells at area tailgate markets. And while “The Little Garden With Big Ideas” is not her principal source of income, it is time-consuming and labor-intensive. “I think it’s a problem for any farmer, male or female, [to get] people to take you seriously because of the size of your project,” she notes. “A lot of people look at what I’m doing and say, ‘You’re just doing a hobby farm.’ But a hobby is something that costs you money; it’s not something that makes you money.”

Janes’ experience is not uncommon. The census shows that typically women are not heading up large operations. Most women-run farms are 179 acres or less, with many less than 50 acres. By comparison, the average farm size is 434 acres, and large-scale commercial agricultural properties often exceed 1,000 acres.

But even though fewer women are operating the “Big Ag” farms that bring in billions of dollars nationally, a significant number of women are involved in farming. In addition to the nearly 300,000 principal operators, women account for 67 percent of the country’s secondary farm operators — typically because their spouses are considered the principal operator. And according to Carol Coulter, executive director of Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture, that’s particularly true in the High Country, the area the Boone-based nonprofit serves.

“A lot are young,” Coulter notes. “Some are single and running the farm by themselves; some have husbands, and they work together on the farm. But a lot of women are driving the farm movement. In our region, at least, I think a lot more women are getting into it than men.”

The nonprofit started out in 2001 as an informal potluck gathering for women farmers and their supporters, Coulter says, but today the organization helps strengthen female-owned agricultural businesses by offering conferences, workshops and farm tours (where men are also welcome). The group has covered topics ranging from raising livestock to understanding agriculture laws to managing interns or hiring migrant workers. As part of that business training, BRWIA also advises women on how to diversify economically to support themselves throughout the year.

“We caution folks not to quit their day job until their farm job is actually bringing in enough income,” Coulter explains. “Right now, in the High Country, unless you have a bunch of high tunnels that allow you to grow year-round, all of these women are working another job to support themselves so they can get back to farming in the spring. It’s a seasonal workforce where women are really farming hard in the summer and doing something else in the winter.”

In corporate farming, massive acreage, agricultural technologies and many hired hands combine to keep production churning year-round. But Coulter notes that the smaller scale, women-owned farms BWRIA supports tend to be less focused on the bottom line.

“The ways that females go about their work is a little bit different,” she says. “Women are more community-minded than men are, and so they bring a different purpose to their farming. It’s communal and social, and I think that aspect is going to play a big role in farming in the future.

“It’s about community development,” Coulter continues. “It’s a piece that’s really missing from that traditional model of the farmer as a man who is independent and just knows how to make it all work.”

For Janes, placing communal learning ahead of profit has been a central component of both Becki’s Bounty and her own farming education. She learned the eco-conscious methods she uses — permaculture, biodynamics, seed saving — by working with peers in classes and conferences offered by ASAP and other groups. And she plans to continue her education on her farm while inviting others to learn with her, hosting community classes and someday adding a hostel where interns can live, work and learn.

“It started as just a way to recuperate from a challenging career,” Janes says. “But now, this is what I really want to do.”

Community growers

Nationally, African-Americans constitute one of the smallest demographics of farmers. It’s a trend that is evident in WNC, where only 46 of the more than 16,000 primary operators surveyed in the 2012 census were black.

Part of the reason for that low number might be history, notes Olufemi Lewis, a founder and worker-owner of Ujamaa Freedom Market. “Especially in the black community, we’re reluctant to develop an interest in farming,” Lewis says. “I think it’s because it reminds us too much of slavery and what our ancestors went through. But there is freedom in growing your own food. It’s empowering.”

For Asheville, at least, black agricultural heritage isn’t all negative. In fact, West Asheville’s historically black Burton Street neighborhood has a long history of community building tied to farming, due in large part to the efforts of E.W. Pearson. A veteran of the Spanish-American War and the first president of the Asheville chapter of the NAACP, Pearson founded the Buncombe County District Colored Agricultural Fair, one of the largest black agriculture fairs in the Southeast. The event was held annually from 1913 until 1947, drawing crowds of more than 10,000.

“I was very young during the agriculture fair, but from what I remember and what I’ve heard, it was a very large event,” says Burton Street resident and Pearson’s grandson, Clifford Cotton. “It ran for about a week, and it was more than agriculture — E.W. Pearson would have Ferris wheels, merry-go-rounds, all types of activities and entertainment for the kids, as well as the agriculture fair.”

The fairs continued until one year after Pearson’s death. No one else in the community held the sway necessary to keep them going, Cotton says, and the fair — and the emphasis on agriculture it created — gradually faded from the neighborhood. The Burton Street Community Association has worked to honor Pearson’s memory, including sponsoring two revivals of the agriculture fair, but efforts to renew interest in farming have not been greatly successful, Cotton says.

“When I was young, you would just sit on the porch and people from next door or down the street would come by and say, ‘I got a bushel of greens I can’t use. Go ahead and take ’em,’” Cotton recalls. “They would just give them to you because they were grown all throughout the neighborhood. But you really don’t see that anymore.

“They’re trying to get the agriculture things built back up, getting the neighbors to grow their own food — preserving, canning like it used to be,” he continues. “But it’s not growing as rapidly as everyone had hoped. Maybe at some point people will realize the importance of having a garden so you can have your own food. That’s one of the things my grandfather tried to instill in the community — to provide for yourself.”

Home gardening, though, doesn’t always lead to the creation of more agriculture-based businesses. And farming, notes Ujamaa co-founder and worker-owner Calvin Allen, simply isn’t a viable source of income for most people, regardless of their race or gender. Instead of merely encouraging people to grow food, Allen says, the community should push its institutions — establishments like churches, schools and hospitals — to form business connections with local growers. “If I knew there was a market for my potatoes — if I knew the school system, for example, would want to buy my potatoes — then that gives me an incentive to grow them,” Allen says. “I think that would bring more farmers to the table.”

Lewis agrees, adding that local restaurants should also do more to source locally. “There will be some things you can’t get locally for a restaurant, but staple vegetables — greens, potatoes, garlic, tomatoes — you should be looking to source those local first,” she says. “ASAP has so many farmers that they work with. It should be a minimum of food trucks that are coming here.”

Lewis and Allen, who work with growers to sell local produce in low-income communities through Ujamaa’s mobile market, know both the value and the challenges of agriculture-based business. On the one hand, the work strengthens a community’s access to healthy foods while providing new jobs — a crucial issue for the city’s African-American community. According to the Census Bureau’s 2013 American Community Survey, the African-American unemployment rate in Asheville is estimated at 15.7 percent, compared with 4.7 percent for whites. As of the 2007 census, only 2.8 percent of the city’s businesses were black-owned.

But on the other hand, the cost of growing food can be prohibitive, especially in a city like Asheville where land is snatched up at increasingly high prices. Then again, some farmers have found ways to capitalize on the overlooked spaces — turning discarded parcels into farms and business opportunities.

That’s the case for the Pisgah View Community Peace Garden, a business that grew out of a neglected baseball field in one of Asheville’s public housing communities. The garden was started by Pisgah View resident Bob White, initially as a community garden providing organic food to the elderly, disabled and homeless. But about 3 ½ years ago, White stepped down and a new group of farmers stepped up.

“I didn’t know anything about growing food, didn’t really know what I was doing,” says current PVCPG operator Sir Charles Gardner. “I didn’t want to see it go back into a baseball field, so I just started getting involved.”

Becoming a farmer meant “a lot of experiments — good and bad,” Gardner says. When he first joined with three other Pisgah View residents to take over the project, it meant learning fast and putting in a lot of hours — 30 to 50 a week in the garden in addition to preparing and selling their produce at local markets. “On a good day we might have $200 to split for the week,” Gardner notes. “On a bad day we might have $60.”

Today, Gardner and Carl Elijah Johnson Jr. are the garden’s main, year-round operators. Two other employees handle bookkeeping and administration, though during the past two peak seasons, grants and other funding have allowed for as many as eight garden workers. The operation sells organic produce and fresh flowers to Pisgah View residents and a few West Asheville subscribers, as well as to local restaurants. They’re also at the West Asheville Tailgate Market.

The business has grown a lot, but Gardner says there’s a long way to go. “It’s still not at a point where it’s sustainable on its own. But we were at a point where we sold $50-$75 a week, and now, on some good weeks, we might make $600-$700 during the summer months.”

And meanwhile, the garden is also helping residents reconnect with growing food. Many have started their own home gardens, he says, while others are attending PVCPG’s cooking demonstrations. “A lot of people are still hesitant about trying the food or just cooking with healthy food,” Gardner explains. “Most of the people who do eat the food from the garden are elderly. The sort of middle-aged generation, it’s hard to reach them. But the kids — we can’t keep the kids out of there.”

The next generation

Killander stands in The Farm’s pasture, thinking ahead to the second season of the CSA and how she can market her yield to attract new customers. More people are interested in buying local foods, and being a woman farmer allows for some advantages, she says. People are often surprised by her and more interested in finding out about her business.

As a woman in her mid-20s, Killander represents a sort of double minority: There are only about 100,000 farmers under age 34 in the country, but Killander says that, too, may be changing.

“In England there’s a huge back-to-the-land movement right now, where people from urban areas are wanting to move to the countryside so they can have chickens and a little garden,” she says. “And I think that’s happening here as well. People understand that there is quality to a lifestyle that isn’t the rat race.”

She may be right. One encouraging note from the 2012 census is that farming among that youngest age group — the one Killander falls into — did increase ever so slightly. But agriculture, notes Killander, is a tough business right now, for commercial operations and small-scale growers alike. For farmers to succeed, they need to be appreciated by their communities, she says — and that’s true for growers of any ethnicity or gender.

“It’s not a woman being a farmer — it’s a farmer,” says Killander. “Whether you’re male or female, you’re still doing that work. It’s honorable work and it’s important work.

“There are different challenges and opportunities, but I think it’s always our job as farmers to remind people that it’s about the work,” she continues. “It’s not about who we are — it’s about what we’re doing.”

This is the first in a series of articles looking at issues affecting minority farmers in WNC. Xpress will continue exploring this topic throughout the growing season.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.