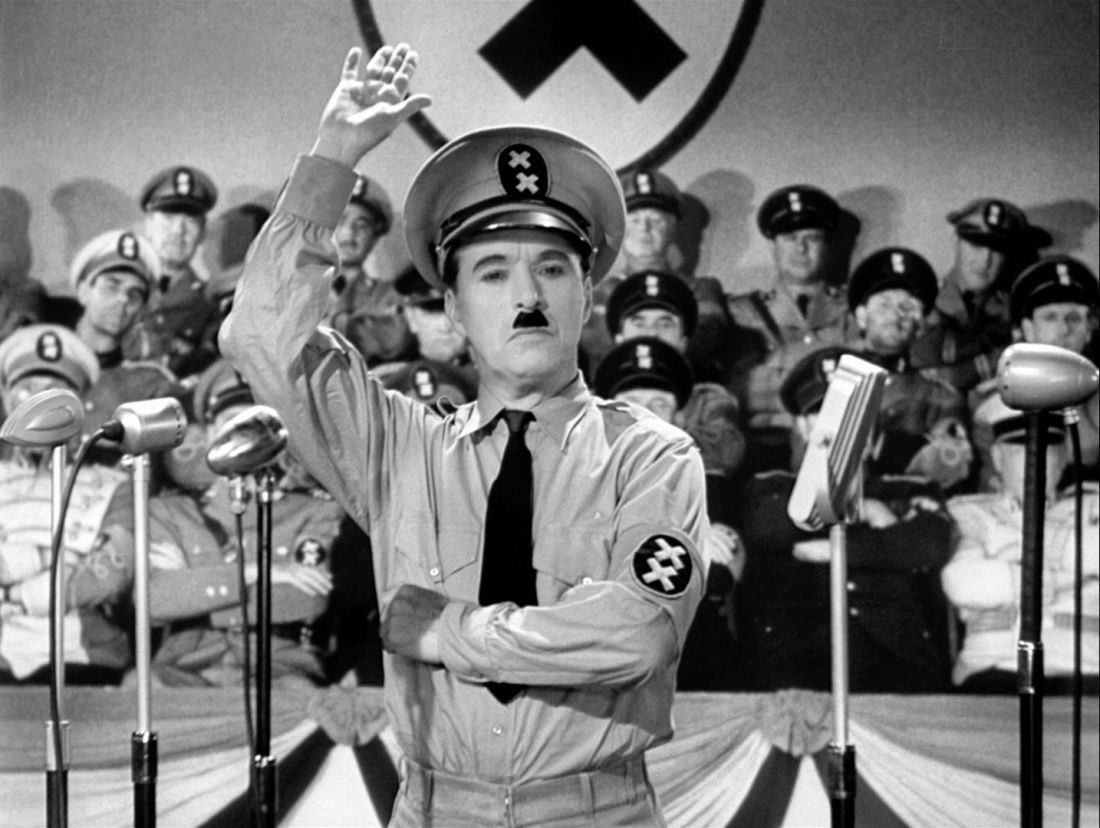

The Great Dictator (1940) marked Charles Chaplin’s late-in-the-day move to talking pictures. He had used synchronized sound — music and effects — in City Lights (1931), had incorporated some talking (always over a speaker or TV screen) in Modern Times (1936) and took the somewhat daring step of allowing his Little Tramp to sing a song in something at least like French near the end. His fear had always been that whatever magic the Tramp had would be destroyed if he spoke. The Great Dictator — among other things — marks the passing of the Tramp, even though elements of him remain in his soft-spoken Jewish Barber character. (Truthfully, it’s less the Barber who delivers the famous speech at the end of the film than it’s Chaplin as himself.) However, there is nothing — apart from Chaplin’s inescapable body language in his Dictator character, Adenoid Hynkel. It is a different character altogether — a ruthless parody of Adolf Hitler that mines every then-known facet of Hitler’s megalomania for comedic, yet sometimes chilling effect.

One of the most treasured experiences of my moviegoing life was seeing every film Chaplin made from Shoulder Arms (1918) through A King in New York (1957) in a package that had been made available after Chaplin’s triumphant return to America for the 1972 Oscars. By 1974, this package had made its way to the University of South Florida — each feature was shown for three nights (Fri-Sun), so that over the course of ten weeks you could see them all. Two of my more intrepid moviegoing friends and I — in the certainty of youth (at 19 I was the oldest of the trio) that what you’re interested in everybody will be interested in — made a mad dash to Tampa the day the season tickets went on sale. We had tickets numbered 0002, 0003, and 0004. So much for the need to rush. Not that the shows weren’t packed — as it turned out, they were — but no one else (save for whoever got no. 0001) was as worried as we were about missing out. I am eternally grateful for this series — which we dutifully traveled 65 miles to see every Friday (sometime returning on Sunday) for the entire run. It gave me a look into Chaplin’s work unlike any other — and I suspect it’s partly why I prefer Chaplin to Keaton by a huge margin.

Oddly, the films seemed to be in no particular order and the first one to show was The Great Dictator and for someone who had never heard Chaplin speak before, it was a revelation — probably similar to the one experienced by moviegoers in 1940. His soft-spoken, precise diction, and his effortless command of delivering dialogue was as thrillingly unique and mesmerizing as his body language had been in the silents. And the vehicle he chose for this debut was a brilliant choice — allowing him a range that no ordinary film would have done. The Great Dictator is no ordinary film. It has certain shortcomings — mostly due to Chaplin’s…er…economy that allowed that the impression of a thing was all that mattered (e.g., when he depicted a long shot of crowd of thousands by photographing grape nuts on a vibrating plate, which works better than it sounds) — but it is nothing short of unique and a masterpiece.

As noted, Chaplin plays two characters. The first is the gentle Jewish barber, who — along with his friends — is saved from the persecution of Hynkel’s stormtroopers by the friendship of a high-ranking officer, Schultz (Reginald Gardiner), whose life he had saved in the First World War. “Strange, I always thought of you as an Aryan,” notes Schultz after he rescues the barber from a stormtrooper lynching, only to have uncomprehending barber tell him, “I’m a vegetarian.” The barber is the ultimate innocent in a world that is rapidly going to hell. How closely related the barber is to Chaplin’s tramp is a matter of dispute even now, but the connection is undeniable — and it undoubtedly helped Chaplin sell the film to his public in 1940.

On the other side of scale is Hynkel. Chaplin may portray his version of Hitler as a buffoon (easily outwitted Jack Oakie’s Benzino Napaloni at every turn) and a spoiled child, but there is nothing even remotely innocent about him. He is a towering — well, short, but towering — figure of evil. He’s also hysterically funny. Chaplin’s fake German speeches sound exactly like Hitler’s rants — untill you listen to them closely and hear the things he’s actually saying — some of which is amusingly spun into something more innocuous by a translator, suggesting that the news we were getting at home at the time was very whitewashed. (A particularly virulent and incoherent tirade against “der Juden” is defused to become, “His Excellency has just referred to the Jewish people.”) It is an amazing performance on every level — and is often as chilling as it is funny.

The truth is that The Great Dictator is a rarity. Even though very obviously a Chaplin film, it isn’t really like any other film he ever made, nor is it in the least like anything anyone else ever made. It was nominated for Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor (Jack Oakie), Best Original Screenplay, and Best Musical Score. Unsurprisingly, it won none of them It was too different, and it was too daring. Not only did it end with a wholly pacifist message, but it openly stated that we were involved in a second world war. (Remember, America didn’t enter the war for almost two years after Chaplin made his film.) It was as much criticized as praised — and, in some quarters, it remains (as do all of Chaplin’s talkies) a controversial work. It is also a work of genius that ought to be seen by anyone who cares about the movies.

The Asheville Film Society is showing The Great Dictator Wednesday, Nov. 19, at 7:30 p.m. at The Carolina Asheville as part of the Budget Big Screen series. Admission is $6 for AFS members and $8 for the general public. Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther will introduce the film.

I’ve seen City Lights, Modern Times, and The Gold Rush at home (thanks Hulu Plus and your Criterion Collection channel!) but must have been subconsciously holding out to have my first viewing of The Great Dictator be on the big screen.

I didn’t realize you hadn’t seen it. As with all comedies in particular, these movies play so much better with an audience, so in that sense you’re better off. When you watched City Lights at your home did you find the boxing scene very funny? If you didn’t, you should see it with an audience.

I laughed a lot at that scene, but even more when the Little Tramp swallows the whistle.

See the boxing match had started to lose its luster with me (remember I first saw it before you were born) — and then I saw it again with an audience and it was an entirely new experience.

This is some kind of retrospective leading up to the release of James Franco’s The Interview?

No.

No or NO!

NO!