Military service is difficult enough, but for many, life gets even harder once they’re done. Over half of the 2.5 million soldiers deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan during America’s longest continuous period of war have returned with mental health conditions directly related to their time in uniform. Twenty percent have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and 1 in 6 struggles with addiction, according to Justice For Vets, a nonprofit advocacy group. Often, the two are related: More than 2 in 10 veterans with PTSD also have substance use disorder, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

And instead of getting the help they need, too many veterans wind up behind bars. In 2010, the Office of National Drug Control Policy estimated that 60 percent of veterans in the prison system were struggling with SUD, and about 25 percent of incarcerated veterans said they were under the influence of drugs when they committed their crime.

In the past year, however, a new program funded by Buncombe County and the Governor’s Crime Commission has begun offering a ray of hope fo some local, imperiled veterans. Operated in collaboration with the Charles George Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Veterans Treatment Court is helping some of those who are struggling the most find a foothold en route to a successful future.

Trauma tales

Mental health issues and addiction aren’t limited to those who actually saw combat. Some people entering the military already struggle with addiction, and both training and active duty offer ample opportunities for trauma. In addition, people often leave the military without any plan for the rest of their lives.

Nick Albizo was a boatswain’s mate in the Navy. He served for over three years, including time in Norfolk, Virginia, and in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. And even though he never went to war, his experiences triggered PTSD.

He was physically assaulted several times, both during training and later by resentful subordinates. To make matters worse, says Albizo, he worked up to 120 hours per week, sometimes under extremely stressful conditions such as severe cold. On one tragic exercise, he witnessed a fellow serviceman’s accidental beheading.

Albizo also had a history of substance abuse. While growing up in Shelby, N.C., he had surgery and developed a dependency on opioid painkillers after being prescribed “pretty much an unlimited supply.” He was supposed to use them as needed but says it’s inevitable that anyone in that position will end up abusing them.

In the Navy, Albizo couldn’t do the drugs so he switched to alcohol, essentially replacing one addiction with another. He was discharged from the Navy several years ago for medical reasons involving alcohol abuse, PTSD and a benign brain tumor.

“They weren’t able to operate on it, so they didn’t know what to do. They felt like I was more of a problem than I was someone they could help. I think that’s why they made the decision to send me home and not even try to give me treatment,” he explains. Within 18 months, however, the Navy did see fit to give him an honorable discharge, making him eligible for VA benefits.

Albizo then returned to Shelby, where he began self-medicating for chronic hangovers with marijuana and then benzodiazepines. “The benzos is what really got me,” he reveals. “I started doing benzos more than I should have, and I combined benzos with pain pills or opiates.” That, he says, resulted in a drug charge and subsequent probation, and when he got caught buying drugs he wound up in the Rutherford County Jail looking at potential prison time.

Albizo says his probation officer felt he needed a more comprehensive approach than standard rehab, so she reached out for information about Veterans Treatment Court. Albizo moved to Asheville last November, and he’s now in a drug and psychological treatment program geared to his particular needs.

“I’m pretty proud of my story, because I’ve made it this far,” he notes.

Treatment vs. incarceration

Drug treatment courts got their start in the early ’90s. North Carolina came on board in 1995, and they’ve since grown in popularity across the state. According to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, “Drug courts have a remarkable track record” over the last 20-plus years. Even during difficult economic times, they’ve proved “to be a smart, cost‐effective investment that helps put offenders on the road to recovery, effectively reducing recidivism.”

So far, the Buncombe County program is looking very cost-effective. A February assessment by Jamie Vaske, an associate professor of criminology and criminal justice at Western Carolina University, extrapolated that even with just seven participants, the program had already saved taxpayers more than $213,000, compared with the cost of sending them to prison. Currently, there are 12 participants, and according to Vaske, the court is saving either the county or the state (depending on where they would be doing their time) over $22,000 per year, per participant. With annual funding of about $75,000, Veterans Treatment Court is designed to serve 30 veterans at a time; at full capacity, substantially greater savings could be expected.

Money aside, the program is a good fit with the respective missions of both the court system mission and the VA. Social worker Katie Stewart, a veterans justice outreach specialist at the local VA, says the “accountability offered by the court system” is a good fit with the VA’s desire “to decrease future criminal justice involvement with the veterans we serve and support their recovery from substance dependence and mental health disorders.”

The voluntary Buncombe County program is the only one of its kind in the state that’s tied to the Superior Court system, though there are others that work with lower courts. District Attorney Todd Williams discussed his desire for such a program during his 2014 election campaign. Williams also credits the programs presiding judge, Superior Court Judge Marvin Pope, whose passionate support helped get the program going and who now actively recruits qualified participants, including Albizo.

A team effort

One impetus for Veterans Treatment Court, says Williams, is that although the local drug treatment courts are useful, they’re not necessarily the best fit for a veteran whose primary diagnosis is mental health-based, such as when substance abuse is an offshoot of a problem like PTSD.

Social worker Eric Howard, the coordinator for Veterans Treatment Court, agrees. “The sole focus of drug treatment court is on the actual addiction,” he explains. “But from the research we’re looking at and from what I’ve learned about the veterans program, so much of the addiction is fed by some sort of PTSD from … military service.” One program participant, for example, smoked meth in part because he didn’t want to go to sleep for fear of recurring nightmares.

With his background in social work and education, Howard (aka “Big E”) is a firm believer in a holistic approach to problem-solving. He draws on resources all over the county, but it’s the collaboration with the VA Medical Center, he says, that really makes the program work. “They have more of a socialized medicine model,” he explains. The veterans “have everything there, they have access to care,” with different departments focusing on addiction, homelessness and so on.

Howard also believes the combination of treatment, therapy, support and accountability could be equally helpful for plenty of folks who don’t have a military background but are facing similar issues, noting, “If only we could do that for all citizens.”

Stewart also sees the symbiotic relationship as key. “The involvement of our veterans in VTC seems to greatly improve engagement and commitment to treatment services,” she reports.

Even veterans she met through jail outreach, continues Stewart, are more committed when their treatment program is bolstered by the support services the special court provides.

Part of that support comes in the form of a mentor assigned to each participant. Retired attorney Rich Schumacher, a former Buncombe County assistant clerk of court, coordinates the program’s mentoring component. Besides having a strong understanding of the legal system, he served three years in the Army, including a stint with the 1st Infantry Division in Vietnam from 1968-69. “Fortunately I got lucky and came back in pretty good shape,” he explains. Now he leads a small, all-volunteer corps of veterans who do mentoring work with their assigned participant each week. “I’ve always been interested in veterans issues,” says Schumacher, but what really got his attention was the roughly 3 percent recidivism rate for such courts nationwide. I said, ‘Hey, this is a program that really does work.’”

Although the mentors aren’t part of the core treatment team, “We are an integral part of the whole system,” says Schumacher. And, unlike most treatment team members, they’re veterans themselves. That, he continues, “gives the participants someone they can probably trust a little bit more, at least initially, because you have common experiences.”

Playing a role not unlike that of a sponsor in a 12-step program, mentors attend court dates and meet socially with participants.

Albizo’s mentor, Kevin Rumley, is a medically retired Marine who works as a veterans outreach coordinator and certified substance abuse councilor at NC Brookhaven Behavioral Health in Asheville. Rumley says he tries to help clients find replacements for drugs and alcohol and healthier ways to manage trauma symptoms.

Albizo, meanwhile, says he feels sufficiently inspired by what Kevin does that he’d “like to pursue a career in that myself.” That’s exactly the sort of buy-in that Schumacher says he’s looking for. In fact, as veterans complete the treatment court program and get their lives back on track, he hopes to recruit some of them as mentors.

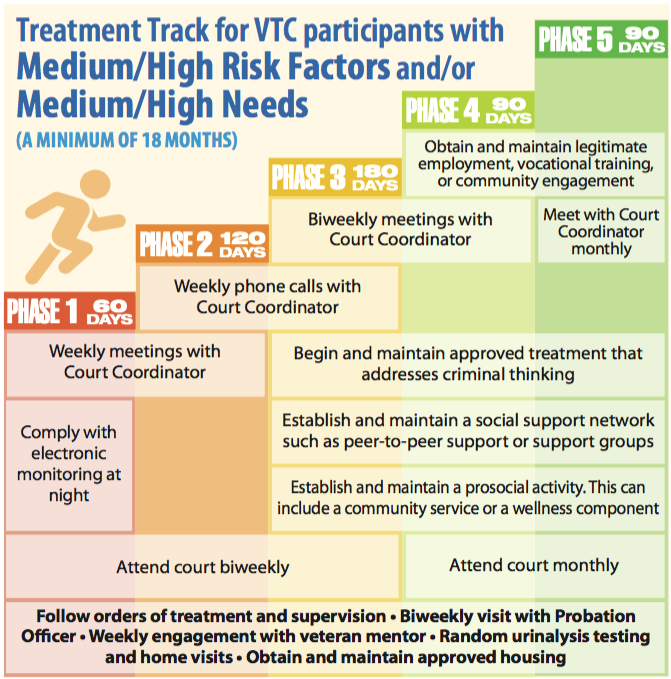

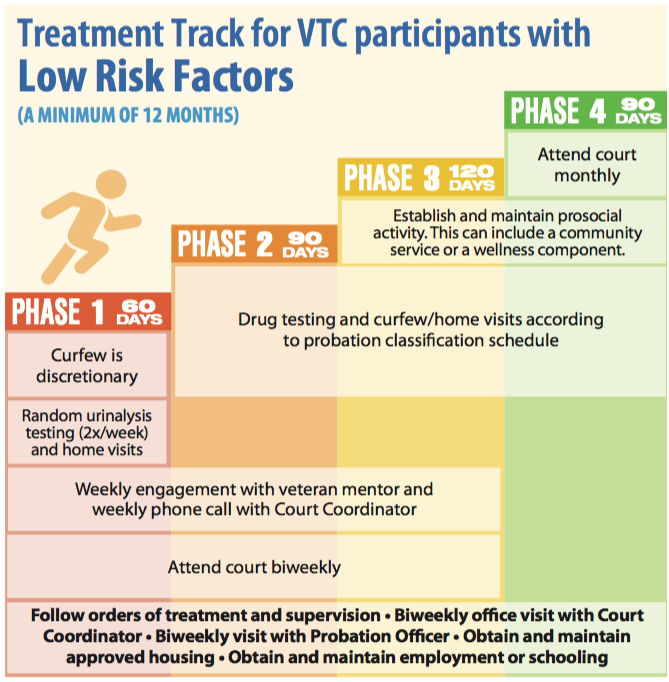

GETTING ON TRACK: The Buncombe County Veterans Treatment Court has two tracks, which are assigned to participants depend- ing on risk and need. Currently, one participant is on the low-risk track, and the other 11 are on the longer track. Although each phase is marked with a minimum number of days, participants must comply with the terms of the phase and produce negative urinalysis screens for a certain number of days prior to advancing to the next level. This can lengthen the amount of time spent in each phase. Graphic by Scott Southwick

GETTING ON TRACK: The Buncombe County Veterans Treatment Court has two tracks, which are assigned to participants depend- ing on risk and need. Currently, one participant is on the low-risk track, and the other 11 are on the longer track. Although each phase is marked with a minimum number of days, participants must comply with the terms of the phase and produce negative urinalysis screens for a certain number of days prior to advancing to the next level. This can lengthen the amount of time spent in each phase. Graphic by Scott SouthwickThe road to recovery

Although Veterans Treatment Court doesn’t focus on punishment, it is hardly a Get Out of Jail Free card. The challenging, intensive program combines therapy and self-improvement efforts with accountability provided by the judicial system and a tough, but fair, team of parole officers.

To “graduate,” participants must advance through four or five phases over a minimum of 12 to 18 months. By the end, they have to have put together some version of a sustainable life, including negative urinalysis screenings, approved housing and either employment or schooling.

Albizo is now about six months into the program and has entered phase two. He has a long way to go and a lot more milestones to reach, but he’s sober and living in a sober environment.

Has he had setbacks?

“Kinda sorta, I would say. But it wasn’t really major. I did relapse, but I bounced back from it the same day. I informed my P.O. and my coordinator and let them know what happened.”

He’s also broken curfew on occasion, but overall, Albizo feels he’s on track, and his confidence in himself and the people working with him is growing.

“I’ve still got my trust issues because of my past. But these guys, the whole team, they’re pretty hard-core. They’re tough but they’re reasonable at the same time. I like ’em,” he admits. “Do I wish I had done stuff differently before it got to this? Yes. I wish I wouldn’t have gone down this road … but I’m in this situation for a reason, so I’m gonna take it as a blessing and do what I gotta do.”

And as the program approaches its first anniversary, Williams, the DA, has high hopes for it. “Veterans Treatment Court is an exciting collaboration with a public benefit,” he says. “I just feel it’s our ethical duty to extend these services and to create this court to broaden our efforts in striving for justice.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.