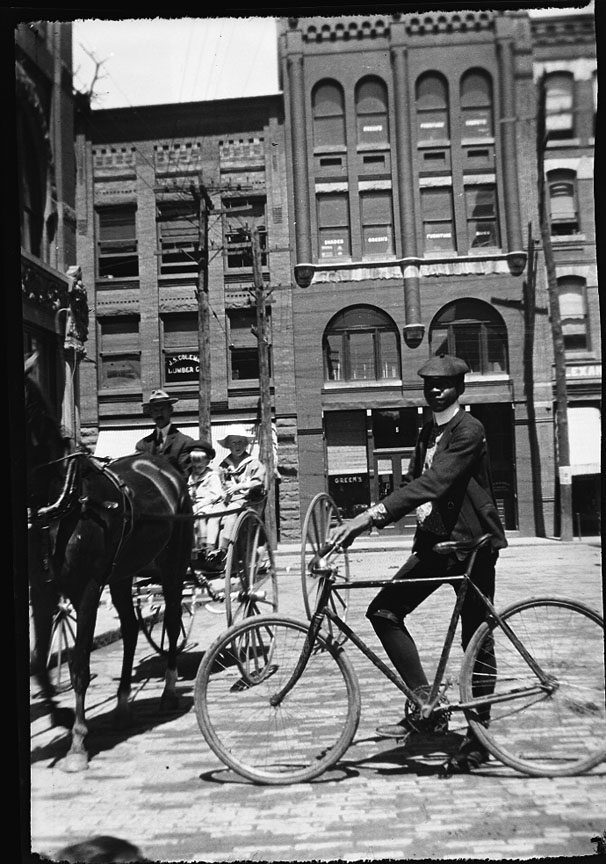

“The bicycle craze is in full force and effect in Asheville right now,” declared the May 12, 1893, edition of the Asheville Daily Citizen. “The wheelmen fill the streets every afternoon and evening after work hours, and the miles of paved streets offer inducements for this form of exercise never known before.”

The phenomenon — by no means unique to the mountains of Western North Carolina — is widely attributed to John Kemp Starley’s 1885 invention of the modern bicycle, equipped with equal-size wheels and a chain drive. Across the country, newspapers covered the popular new trend with interest and zeal. Between 1890 and 1900, the phrase “bicycle craze,” appeared in nearly 7,000 newspaper articles.

During this same period in Asheville, a number of cycling groups formed, including the 1895 West End Bicycle Club, the 1897 YMCA Bicycle Club and the 1900 Citizen Bicycle Club. Typically, these groups gathered once a month to tour the town.

Advertisements for bicycle shops also started appearing more regularly in the dailies. In 1893, the Asheville Bicycle Co. promoted a range of options that cost between $20 and $150. All new purchases, the company noted, came with complimentary cycling lessons “by competent instructors.”

The following year, local shops began highlighting the benefits of cycling in their advertisements, as well. One promotion read:

“As an exercise bicycle riding is unsurpassed. As a means of getting from place to place with rapidity, the bicycle is unequaled by either horse or street car. In its saving of street car fares alone a wheel will in a short time pay for itself.”

However, trouble soon emerged for the new mode of transportation. On Aug. 21, 1897, The Asheville Daily Citizen reported that one local resident, E. Coffin, was urging the Board of Aldermen to adopt measures that would “lessen the danger to the public from reckless riding of bicycles[.]” Coffin asked that all riders be required to use “a lantern, gong and brake,” while navigating the streets by wheel.

A week later, City Attorney Locke Craig shared a proposed ordinance that would prevent riders from coasting, limit cycling speed to 10 miles per hour and require that all night riders be equipped with a headlight, as well as “a bell to ring continuously.” The board approved the ordinance on first reading, sans the continuous-bell clause. Further discussion would be held at its next meeting.

A challenge to certain aspects of the ordinance was presented in an Aug. 31, 1897, letter to the editor. The writer, who signed his name as “Wheelman,” opposed the ordinance’s requirement that cyclists use a headlight at night. A good lamp was hard to come by, the author insisted: “They are greasy, dirty, smoky and cannot be kept burning half the time and are a positive nuisance[.]”

The letter went on to implore the board to consider the public service bicyclists perform throughout the nation. “The wheelmen of the country are doing more than any other class of citizens to promote the building of good streets and roads,” Wheelman wrote. “I think they should at least be treated fairly.”

The board reconvened on Sept. 3. At the meeting, Coffin once again spoke, advocating for the original proposal, which included a bell that would ring continuously while riders were in motion. According to the paper’s Sept. 4 recap, Coffin also publicly denounced all arguments published in the Aug. 31 letter to the editor. “Mr. Coffin said he believed that a majority of wheelmen do not own property and therefore do not pay taxes to keep up the roads of the county,” the paper declared.

On Sept. 6, The Asheville Daily Citizen featured the official new bike ordinance, which would go into effect on Oct. 1, 1897. Coasting was prohibited; riders could not exceed speeds greater than 8 miles per hour; and warning bells were required, as were headlights. Violators would be fined up to $50.

The following month, on Oct. 2, 1897, The Asheville Daily Citizen reported:

“Patrolman Noland last night arrested the first violator of the bicycle ordinance, Robert Glasco. The young wheelman was riding without a headlight and was summoned to appear this morning in police court. A fine of $2 and costs was imposed by Acting Police Justice VanGilder. The patrolmen do not like to arrest ladies, but the latter are warned to attach lights to their wheels. Bicycles must also have bells attached.”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

Back in those days the term “bicycle” was not in common use. They were normally called “wheels” and their riders “wheelmen”. My dad was born in 1917 and grew up in Asheville. In the 50’s he used to call my bicycle my “wheel” from time to time. In the 1930’s motorcycles were commonly called “motors”. When I started riding in the late 60’s my age group tended to call them “cycles” but my dad still referred to mine as “your motor” ..

I suspect there is a transcription error or an error in the original in this: ” In its saving of street car fares along a wheel will in a short time pay for itself.” I believe the word “along” should be “alone”.

Regards,

Mike