“A year ago influenza was raging [here],” The Asheville Citizen reminded its readers on Oct. 25, 1919. And while new cases of the virus were appearing outside the region, city residents were “practically immune from the disease,” the editorial claimed.

Despite Asheville’s clean bill of health and the paper’s wildly optimistic outlook, readers were still advised to remain vigilant. “The people should … consistently and rigidly practice all those rules for health and freedom from infection that were learned last year,” the editorial continued.

For a period, the message appeared to work. But when six new cases emerged in late January, city officials stepped in. “While there is said to be no cause for alarm here, the city health officer thinks the people should not hold unnecessary meetings for awhile,” The Asheville Citizen reported on Jan. 25, 1920.

Five days later, on Jan. 30, the causal recommendation became an official declaration. That day, the paper reported 232 new cases within a 24-hour period. In response, the city ordered a shutdown, closing all schools, theaters and nonessential businesses — just as it had in 1918. Meanwhile, according to the resolution, all churches and religious institutions were “respectfully requested to suspend all gatherings of any kind[.]”

Most local churches obliged. In one case, reported by The Asheville Citizen on Feb. 1, 1920, the Rev. Anton VerHulst of Montreat went so far as to mail “a special sermon” to the members of his congregation to remain in compliance with the city’s request.

But a few religious leaders resisted the appeal. On Feb. 5, 1920, The Asheville Citizen wrote that the Rev. J.O. Ervin intended to hold a service that Sunday at Bethel Methodist Church. In a statement provided by the pastor, Ervin asserted that “the great business of encouraging and restocking of the inestimable treasures of faith, hope and love” could not be denied. Further, the pastor argued, “people who regularly attend the house of worship are, as a class, the most sane, sanitary and saintly people of the community,” and thus “the safest aggregation of individuals with whom it is possible to mingle with.”

Not everyone was convinced. In a letter to the editor published on Feb. 6, 1920, former Bethel Methodist member George A. Shuford implored current congregants to “allow Bro. Ervin to hold his services all by himself[.]”

The paper’s editorial board also expressed its disapproval. “To say that religion and worship cease when the church closes is to deny the omnipresence of God,” it wrote on Feb. 12, 1920.

But in the same day’s paper, in a letter to the editor, Willis G. Clark, rector of Trinity Episcopal Church, came to Ervin’s defense. Clark, like Ervin, was among the minority of religious leaders still holding sessions. “This was not done in defiance of any law nor to be ‘contrary’ to any request of the health or civic authorities,” Clark wrote. “[B]ut to bear witness to the fact that God’s House must not be looked upon as a place of danger in the time of need of Divine Power[.]”

Church leaders were not alone in challenging the order. Early on, county teachers had also insisted that their schools remain open, pointing to the fact that rural areas experienced no new influenza cases. Though their initial protests failed, county schools did reopen on Feb. 14, three weeks before city schools welcomed back their students on March 3.

Most restrictions, however, were lifted on Feb. 29, 1920, following a steady decline in infection rates. Weary of flare-ups, The Asheville Citizen implored residents to remain cautious in that day’s editorial:

“A year ago more than one flare-up of influenza occurred here, due, so far as science could determine, to unrestricted mingling of the people. Caution and restraint may spare the city the trouble, sickness and death that may be expected to accompany such fresh outbreak of the epidemic.”

According to contemporaneous news reports, the city experienced more than 2,000 cases of influenza and 31 deaths over a five-week period starting Jan. 25, 1920.

Editor’s note: This is an ongoing series that examines the impact of the 1918 influenza. Previous articles can be read at the following links: avl.mx/73d, avl.mx/73e, avl.mx/73f, avl.mx/73g and avl.mx/74e. Spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

These articles are great. And so helpful to pass along to people who try to tell me that we didn’t close things down in 1918 or explain why it is safe to go maskless or open up immediately because there haven’t been that many cases here or [fill in ignorant opinion here]*. Keep up the good work! And thank you.

* Seriously. I heard a young person who described himself as “progressive” declare he was safe from getting Coravid-19 because he “didn’t belong to one of the risk groups.” I told him real progressives believe in science, medicine and education… he was singing from the Trump hymnal.

A study from 1920 seeking a reason for the failure of cloth masks required for the public in stopping the 1918 influenza pandemic, found that the number of cloth layers needed to achieve acceptable efficiency made them difficult to breathe through and caused leakage around the mask. We found no well-designed studies of cloth masks as source control in household or healthcare settings.

In sum, given the paucity of information about their performance as source control in real-world settings, along with the extremely low efficiency of cloth masks as filters and their poor fit, there is no evidence to support their use by the public or healthcare workers to control the emission of particles from the wearer.

Apparently the “ignorant opinions” include yours.

Apparently your education is as old as those studies. Believe it or not we’ve made many scientific and medical advancements in the 100 years since then. Frankly I’ll take the views of scientists and health care exerts like the CDC over pseudo-intellectuals like you.

“You have no power here. Be gone… before someone drops a house on you, too.”

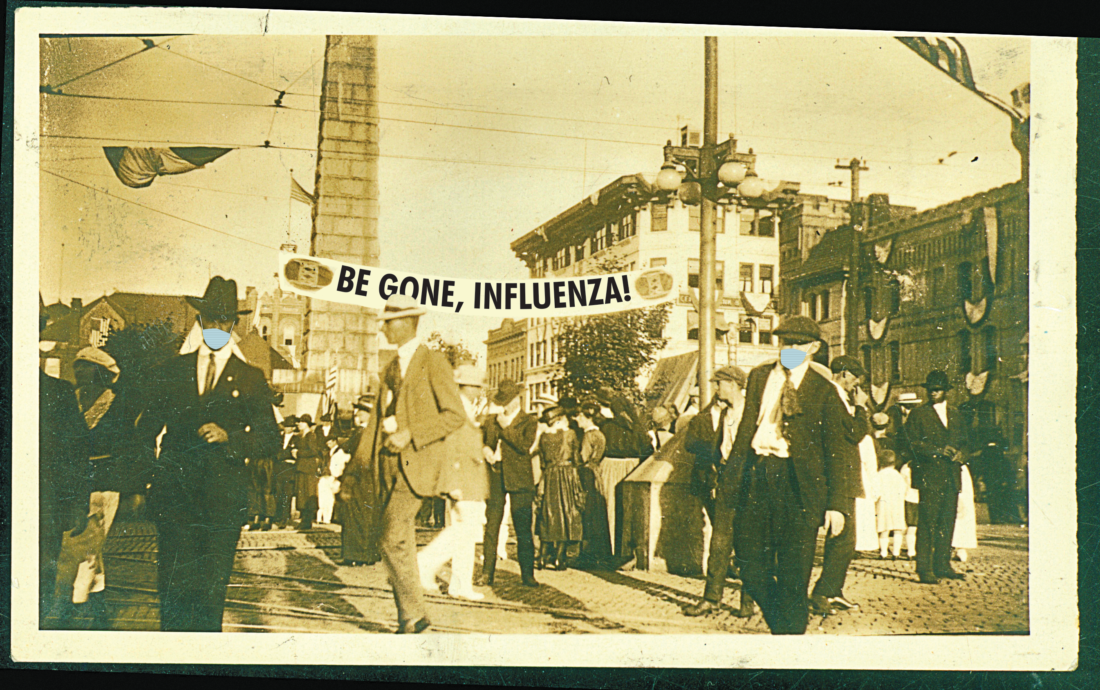

Great article and I always appreciate these throwbacks in the Mtn Express. Terrible photo shop hack.