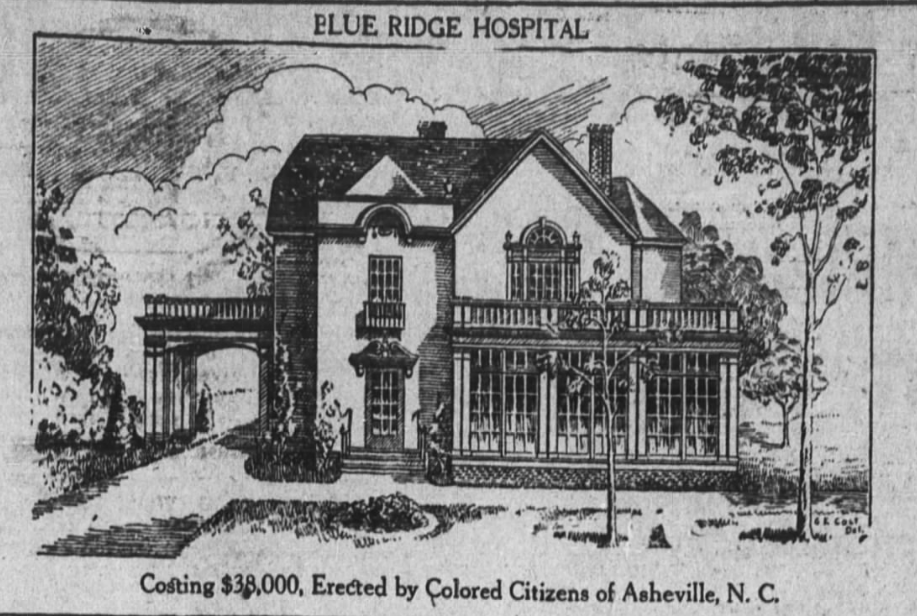

“The formal opening … of the Blue Ridge Hospital for colored people is an event in which both races in Asheville may well take pride,” The Asheville Citizen declared on Sept. 25, 1922, three days before the grand event. “[F]ounded through the joint efforts of whites and blacks, [the hospital] will be a lasting testimonial of the friendly relations of the races in Asheville and of the desire of their leaders to work together in those activities which mean the advancement of Negro welfare.”

Before its launch, the city had no dedicated medical facility to treat its African American residents. A previous clinic — Torrence Hospital, which opened in 1910 — had closed by 1915, following the untimely death of its founder, Dr. William Green Torrence. (For more, see “Asheville Archives: The short life of Dr. William Green Torrence,” Feb. 20, 2018, Xpress)

Along with local pride, Blue Ridge Hospital garnered national attention. On Oct. 7, 1922, The New York Age, a Black-run paper, featured an in-depth report by writer Alonzo A. Rives, who stated that Asheville’s 8,000 Black residents “are as progressive as any group of people found south of the Mason and Dixon line.” The hospital, Rives continued, stood as “one of the monuments of their progress.”

According to Rive’s report, the facility could house up to 30 patients and included a sun parlor, a maternity ward and “ample ambulance service for the injured.”

In addition to being the “only hospital exclusively for colored patients in western North Carolina,” Rives spotlighted the organization’s on-site training school for Black nurses. The article went on to list the facility’s all-Black staff: Dr. R.H. Bryant, president of the board of trustees; Dr. J.W. Walker, chief surgeon; Dr. L.O. Miller, dean of nurses staff; Dr. J.W. Holt, house physician; Dr. I. N. Giagego, anesthetist; and Miss A.M. Wood, superintendent.

Three years later, on May 21, 1925, Lula R. Long, Flossie May Metz and Mary Kathleen became the first three students to graduate from the hospital’s nursing program.

“More than an incident,” The Asheville Citizen declared that day, “it is an epoch.”

The article continued its praise of the program, although some of its compliments were paternalistic and included generalizations and stereotypes about African Americans.

“The initial coterie of young colored women, expert in caring for suffering humanity, will doubtless be followed each June by other graduations which will ultimately make of this city a center of skilled practitioners ready to give to the negroes of North Carolina every benefit that knowledge can supply, advantageously presented with a sympathetic understanding that is an inborn characteristic.”

The paper also used the event to commend the community’s white citizens, insisting the hospital’s success could not have happened without their input and aid.

At the same time, The Asheville Citizen cautioned against complacency among citywide support, noting the hospital’s ongoing needs. At odds with Rives’ earlier report, the local paper stated that Blue Ridge Hospital lacked a maternity ward. Further, the facility did not provide housing to its nurses (common at the time) and its “quota of laboratory equipment is pitifully inadequate.”

Despite some of its shortcomings, the article concluded with high praise. “Its operating room supplies are admirable; its facilities for sterilization are splendid,” the paper wrote. “Hard work characterizes the efforts of its personnel and enthusiasm marks the spirits.”

Subsequent reports state the Blue Ridge Hospital closed either in 1929 or 1930 due to the Great Depression. In 1943, the Asheville Colored Hospital became the next major Black medical facility to open in the city during segregation. (For more, see “Asheville Archives: Asheville Colored Hospital opens, 1943,” Xpress, Sept. 18, 2018).

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original document.

Where was this located??

Hi AJV,

The hospital was located at 18 Clingman Avenue. Thanks for the question and thanks for reading Xpress.