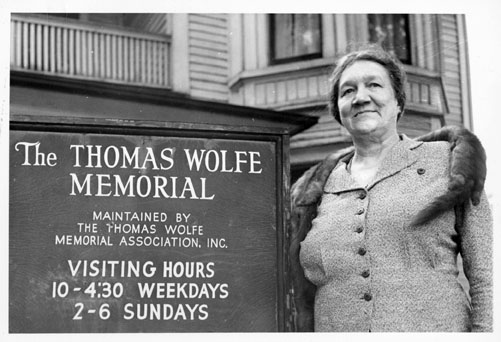

On Sept. 30, 1958, The Asheville Citizen notified readers that local resident Mabel Wolfe Wheaton had died, succumbing to complications from diabetes the previous day. Wheaton, the older sister of writer Thomas Wolfe, had outlived her famous brother by more than two decades, following his untimely and premature death on Sept. 15, 1938.

Since his passing, the obituary noted, Wheaton had become “the greatest living authority on the man who was becoming a literary giant.”

At the time of her own death, fans of Wolfe’s 1929 debut novel — the highly autobiographical Look Homeward, Angel — were certainly familiar with parts of Wheaton’s personality and personal history, thanks to her inspiration for the character of Helen Gant, who possessed “a restless hatred of dullness, respectability.”

Like Wheaton, the character of Helen joined the vaudeville circuit with a fellow friend in the early 1900s, singing at moving-picture theaters throughout the country. In his novel, Wolfe describes Helen’s missives home about her travels, writing:

“Her letters beat like great pulses; they were filled with the excitement of new cities, presentiments of abundant life. In every town they met ‘lovely people’ — everywhere, in fact, good wives and mothers, and nice young men, were attracted hospitably to these two decent, happy, exciting girls. There was a vast decency, an enormous clean vitality about Helen that subjugated good people and defeated bad ones.”

According to her obituary, Wheaton continued to travel in her later years, though on the lecture circuit, offering insights to literary audiences about her brother. She also “recorded tirelessly for the Library of Congress her recollections of the Wolfe family, the ‘Gants’ of Look Homeward, Angel, Wolfe’s first and best known novel,” the paper stated.

Shortly before her death, Wheaton had begun work on her own book, Thomas Wolfe and His Family, co-written by author Willam LeGette Blythe. Published posthumously in 1961, it offers a unique look at Asheville near the start of the 20th century.

In one passage, Wheaton describes traveling amid the Flood of 1916. At the time, she and her husband, Ralph Wheaton, had just celebrated their wedding and were trying to make it to Raleigh. They initially stopped in Chimney Rock, 25 mile east of Asheville. Wheaton notes:

“That sounds like a short distance for a day’s travel. But we had got away from Asheville late and we stopped well before dark. For one thing, in those days motorists were always fearful that their carbide headlights wouldn’t function; there was little night traveling. Besides, the highways then, compared with the present concrete and asphalt ribbons that cross and crisscross North Carolina and the nation in every direction, were little more than sand-clay trails few and far between.”

As the rain fell, the couple continued eastward but ultimately stopped in Forest City due to the weather. “The rain poured, the skies seemed veritably to open, and the water came down in torrents,” the book reads. “For two or three days we had to stay holed up in [a] leaking hotel.”

Eventually, the newlyweds forged ahead, crossing a bridge “we could not see the floor of,” Wheaton relays in the book. “It was a foolish thing to do, we agree now, but then we were young and the caution of advancing years had not settled upon us.”

In another of the book’s passages, Wheaton describes the arrival of the circus to Asheville around 1903.

“My Asheville friends whose memories do not go back that far may find it hard to believe, but this particular carnival was set up just below the towering Vance monument, between it and the old City Market that was just below Papa’s building. One of the carnival tents was right in front of Papa’s place, which was where the present Jackson Building, Asheville’s tallest structure, now sits.”

Inspired by the circus acts, the Asheville youth quickly re-created the magic. “Well, that carnival had hardly pulled up stakes and departed our town when the children in our Woodfin Street neighborhood determined to put on a carnival of their own,” the book reads. “It was decided to stage it in our back yard.”

The impromptu gathering, continues Wheaton, was decided upon without parental knowledge or consent. “Certainly had [Mama] known what acts were being planned, she would have put her foot down,” Wheaton states. “And though Mama’s foot was small, she could put it down heavily and effectively.”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents. Special thanks to the Thomas Wolfe Memorial for providing excerpts from Thomas Wolfe and His Family, as well as fielding additional research questions.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.