A visitor to Evan Gray‘s home in Asheville would likely find plenty of poems throughout the domicile.

“I love collecting journals and keeping my drafts scattered around a bunch of notebooks before moving to drafting them on a computer,” Gray explains. “I try to keep a kinesthetic relationship with writing as much as possible.”

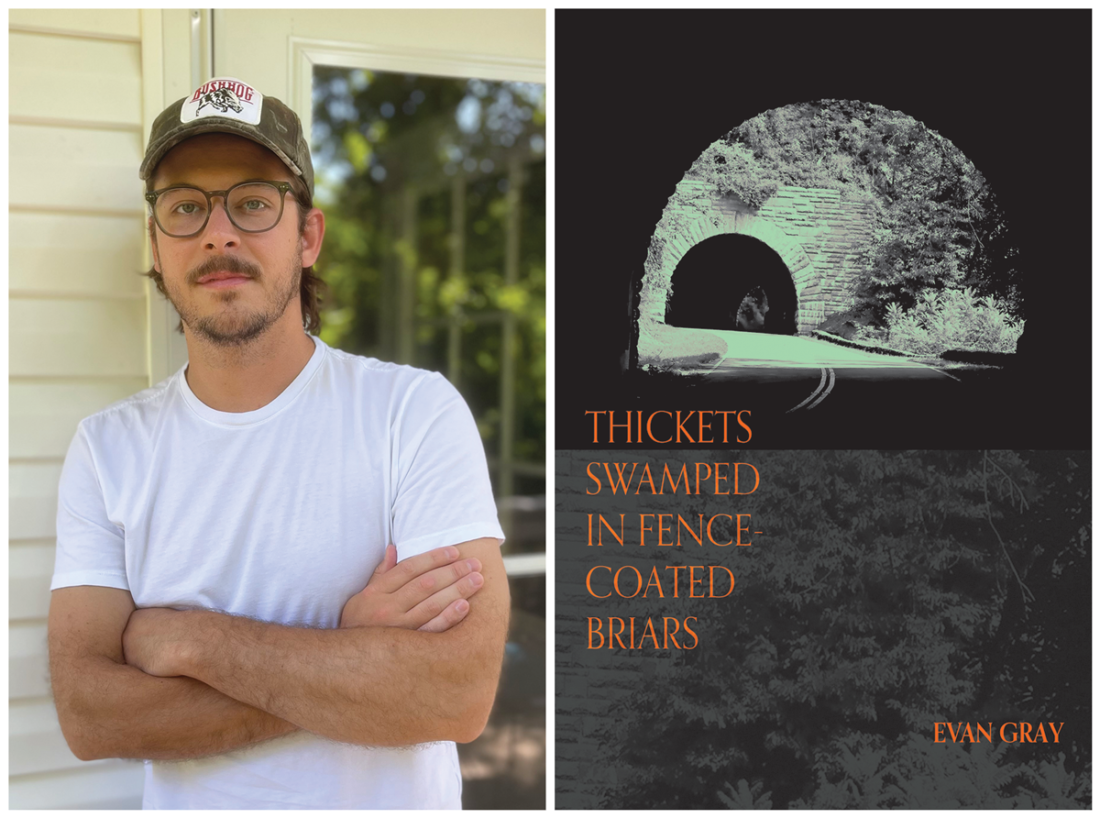

His preference to write longhand seems fitting when you read Gray’s debut collection, Thickets Swamped in Fence-Coated Briars. Released in October, the collection explores the physical and psychological tolls of life in Appalachia. Informed from his own upbringing in Jefferson, the region’s land and lost industries haunt the debut.

In this month’s poetry feature, Xpress speaks with Gray about the influence of Western North Carolina on his poetry as well as his efforts to write against stereotypes that often show up in Appalachian-based works. In addition to the chat, Gray also shares his book’s opening poem, an untitled piece that he describes as the collection’s prologue.

Xpress: Speak to me about the prologue itself and how you see it working with the rest of the collection.

Gray: I wanted to start the book with a type of reference point to give the readers context to the Appalachia I am talking about. I feel like it gets represented in a way where its beauty is almost mystical and nothing bad ever happens. The opposite is true, too. Sometimes people think of Appalachia as being backward or full of all these issues that don’t exist anywhere else in America. I didn’t want to do that, either. I wanted it to be real, real to me and what I have lived.

Has place always featured prominently in your poetry? Or has Appalachia started showing up more recently in your work?

I think everything I write is concerned with my home. Western North Carolina, specifically a plot of land in Glendale Springs, N.C., has been in my family since the late 1790s, before Ashe County was even formed. I grew up on that land, my dad grew up on that land, his grandfather built a house there and so on. I’ve come to terms with the fact that everything I write will be labeled as Appalachian in one way or another. If I write a science fiction novel, it will be considered Appalachian. If I learn to sing opera or get really good at painting, whatever I do will be considered Appalachian. That’s fine.

Is it fine, or am I picking up on some slight resentment?

I think some folks definitely have assumptions about what makes a book or a poem “Appalachian.” I find most Appalachian writing buying into some of the marketable stereotypes from the region instead of saying or doing anything interesting. There’s tremendous pressure out there for some writers to ask themselves — “Is this Appalachian enough?” — before sending stuff out into the world. I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in what comes natural to me, and it just so happens that I’m from the mountains. It’s unshakable.

Shifting gears here, a lot of your poems are written in sections. Can you speak to this approach and choice?

I feel like sections are the form that best represents what I’m trying to do in this book. I think my role as a poet, at least with this project, is to observe. I’m reminded of Walt Whitman when he wrote, “I think I will do nothing for a long time but listen” in Leaves of Grass. Individual short poems are great. Some of my favorite poems in the world are short and encased on one page with a title, and they look all neat and pleasing. But for Thickets, I wanted to include as much as possible as it relates to a place, feeling, image or something else that connects each section together.

I’m also always interested in hearing more about a poem’s shape. In some instances, you’ve got sections that literally look as if they’re melting off the page. In other instances, there is a lot of white space on the page. Could you speak to the general process of shaping a given poem?

The form of the poem or the way it appears on the page is something I fiddle with constantly. I draft a lot of my poems first by hand. I’ll edit then translate them to a Word document when I feel like they’re ready, but I always try to keep some part of the longhand evident in the translation. I’ve also been thinking a lot about the poet being an attentive observer, like I mentioned before. Thickets is in one way about the destruction of land in the name of development. I see the ways these poems look as being about the same thing, just with language.

What role do you see poetry playing in today’s world? And how would you like to see its influence/presence change, if at all?

Man, that’s a big question. Whenever I think about poetry’s function in the world, I’m reminded of Henry David Thoreau who said, in so many words, that it’s amusing how little space poetry occupies in the landscape. I don’t think he said this because he didn’t find it important but rather an outcome of living life, secondary to his main goal of living. I say “outcome” instead of “product” because I do feel like poetry has become increasingly commodified and attached to it are these various points of value — social or other.

There’s little money in poetry, which is why I like it as a medium. However, it does seem like there’s rich social currency coming out of it in online spaces. I’m not really interested in that either. I don’t really read too much contemporary poetry unless they are by authors who I have to seek out. The stuff that filters to the top often seems too concerned with the commodification in one of those previous ways.

As far as its role in society, it’s hard to say. Maybe it offers an alternative way of experiencing language. Maybe it is just a fun little game to play.

Any book recommendations?

One of my favorite local poets is Tim Earley. Tim is from Sandy Mush but lives in Asheville now. He’s been doing poetry for a good long time and he’s excellent at it. I reread his book Linthead Stomp while I was drafting Thickets, and it shook me to my core — so much about labor, grief and living inside Appalachia while industry and other forms of “progress” zoom in to try to rescue it. I believe there’s a collected works of Tim’s writing coming out at some point in the future. I’d say keep your eyes peeled for that.

My buddy Colin Miller also has a new record called Haw Creek. I love everything I’ve heard from it. It’s a good mix of ’90s and Appalachian sound. There’s a dulcimer on one song called “Never Wanna” and it’s so refreshing to hear that kind of stuff. Colin’s a great lyricist, too. I hope everyone gets to listen to that record; it sounds like it was made in the mountains.

Who are the four poets on your personal Mount Rushmore?

If I have a Mount Rushmore of poets, it’s made of littered trash from the creek bed that I can remold at any time. I guess my first installation would be John Milton, Jonathan Williams, Besmilr Brigham and Ola Belle Reed. It would probably change before I could even get the first one built.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.