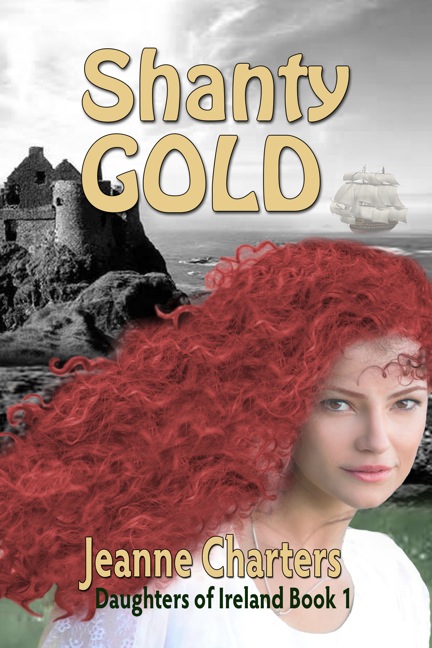

Local author Jeanne Charters will read from her historic novel Shanty Gold at Malaprop’s Tuesday, Oct. 6, at 7 p.m.

The book follows Mary Boland, who loses her mother and sister during the famine in Ireland. “The 13-year-old girl summons the angels of her childhood and the blood of Banshee ancestors to escape the same fate,” according to the book’s description. “Quaking with fear, she boards a ship to Boston to seek her beloved Da. On The Pilgrims Dandy, a coffin ship filled with death and despair, Mary finds a spirit brother — Kamua Okafor, a slave boy from Africa. With his help, she vanquishes starvation, rape, discrimination, sexism, and illiteracy to accomplish her destiny.”

Shanty Gold is inspired by the story of Charters’ own great grandmother. She shares a chapter, below.

Chapter One

May the road rise to meet you.

August, 1849, County Cork Ireland

Near dawn, others join me on the walk to Cobh. Silent stragglers they are, a man, a woman, and a wee boy, dragging behind them paltry gatherings from a lifetime of poverty. At first, their presence is a comfort, but the shuffling feet send dust into the air and me mouth turns to sand.

I spy a pond in the distance and crawl toward it, but the water’s mostly mud. Back on the road, me three companions are gone.

I fall onto the stones. You win, Ireland. Killed me like me kin, you did. ‘Tis a relief to quit this hopeless effort. Time drifts by. So this is how it feels to die, is it? Not so bad.

Lying there, I drift into unconsciousness, but suddenly there are hands, hard hands tugging under me arms and pulling me over a rough rail into a wooden cart. That gobsmacks me brain some, I’ll tell you. I thought I’d left such things as splintery carts behind me.

I close me eyes and fall into sacred sleep. The sun is high in the sky now, so time has passed, but I don’t know how much of it. I yearn to straighten me legs, but boxes cram every inch of space. A blacksmith’s anvil digs into me spine.

Sweet smells of wildflowers drift into the cart. ‘Tis the wondrous scent of summer in Ireland. Could I move, I’d pick some to slake the hunger gnawing me belly, but I’m too tired.

A woman speaks, “Look, Tim. The road to Cork City. We could kiss the Blarney stone.” She laughs. “That’d do us well in Canada.”

Canada? She hums a Gaelic song Mam used to sing. It lulls me back into sleep, but the noisy caw of herring gulls jolts me awake. Da once said, “Blast those birds. Had I a gun, I’d shoot them all out of the sky.”

This day, I’d do the same.

The hands shake me awake. “Girl, who are you? Where are you headed?” He is elderly, nearly as old as me father, with at least thirty years etched on his face, so I try to give a respectful answer.

“Mary Boland, sir,” I say, shocked by the rasp that is me voice. “I was walking to Cobh, but…”

“The blessings of St. Brigid are with you this day, Mary,” the woman says in a voice soft as a lamb’s coat. Her face glows with kindness, like saints on holy cards. She strokes the hair from me eyes. “That’s where we’re headed as well. But the Cork harbor is called Queenstown now, not Cobh. To honor Victoria’s visit.”

I close me eyes again. Who’s this Victoria?

Bits of their talk mix with the sounds of the squawking gulls. “She’s just a child, Tim. Why is she be traveling to Queenstown alone?”

“Let her rest, love. Lots of children have tried to get to the ships. Most don’t make it. She’s a lucky one.”

Night darkens the sky, and rain pounds on me back. A blanket lowers over me, and I sigh in gratitude.

As the sun reddens the East again, I sit up, wincing at the soreness in me hip. Biting wooden splinters out of me hands, I glance up and see them staring back at me. A grin feels silly on me face, but ’tis the best I can do.

“So, you’re Mary Boland, are you?” the man says.

“Yes, sir.”

“We’re Tim and Moira Donahue,” she says. “Call me Moira and him, Tim,” she gestures toward the man.

It is unseemly to call someone her age by her first name, but I’ll do as I’m told. I don’t want to get kicked from this wagon. “Thank you, I will, Moira.”

“How old are you, child?” Her voice is sweet as soda bread.

“What year is this?” I say, knowing that sounds ignorant. “No one in me village kept a calendar.”

“It’s 1849, girl,” Tim answers.

“Well, I was born on St. Patrick’s Day, 1836, but I’m no good at ciphering.” I blush, knowing how stupid they must think me.

“You’re thirteen-years-old then,” he says.

Thirteen is it? My, I’m nearly grown.

“Where are your mother and father?” Moira asks.

I brace me heart against the telling. “Da sailed for America a while back. He said he’d send money for us to come over. We never got it, though. I think the landlord stole it.”

“I wonder if he even survived the trip,” Tim whispers.

Me heart stops. “You think me da’s dead?”

“Nah, girl. He’s probably fine.” His deep tone reminds me of Da’s when he held me on his lap while reading from Gulliver’s Travels.

“And your mother?” Moira asks.

I don’t want to remember, but must. “Mam died a week ago, along with the baby, Ellen.”

The woman’s eyes are brimming when she looks at me again. “I’m so sorry,” she whispers. I can tell she means it.

“What was your village?” Tim asks.

“Kinsale.”

“Ah, lovely place,” Moira says. “On the Great Ocean.”

“Aye, ’twas lovely,” I answer, as images wash over me, green rolling hills, whitecaps and white sails, salmon jumping to the nets, sheep, friends, parties, and family — most of all, family. The memories threaten me speech until hot anger rescues me tongue. “It’s lovely no longer. The ships there fly British flags now.”

Tim grunts. “Since that hoor’s melt English Pope let Henry the Eighth invade us seven-hundred years ago.”

“Hush with your blasphemy, Tim,” Moira hisses, then turns to me, “How did your mother pass?”

I brace me heart against the telling. “Before he left, Da sold his fishing boat and nets and bought oats to last us till he could earn money for our passage. When our sheep died, we had no wool to ship to England. The landlord burned our cottage.”

“Most of our village was burned out this past year,” Tim says, shaking his head. “All that remains there are a few pitiful huts and the landlord’s grand house. We knew we’d be next.” He turns to face me. “Why did you not go to the nuns?”

“Mam wouldn’t hear of it. ‘Bolands don’t take charity,’ she said, and meant it.”

He shakes his head like maybe his mam was proud, too.

“When Mam made her mind up, there was no changing it. So I found us a cave.” I shiver, remembering, and then hug meself so I can go on with the awful next part. “It was cold and wet in the cave. Da had given me his revolver before he left and trained me to use it. I was a good shot. I sold the gun for peat to warm the cave. Then, Mam got the dysentery. I couldn’t make it stop though I tried all the old remedies. I think it was from spoilt soup the British gave us at the soup kitchen.”

Tim’s murmur is harsh. “Bastards! If they can’t kill us by starving or burning us out, they poison us with their putrid gruel.”

“I tried to make Mam better,” I say, swallowing a moan, “but nothing helped.”

Moira touches me cheek.

“When Mam’s milk dried,” I say, straightening me back, “the baby passed quick. Mam died soon after. I think her heart was broken.” The fury of watching them die returns in a rush. Then, the anger turns to grief.

Tears won’t help, but that doesn’t stop them. I brush them away. I never cried, not even when I took the gold cross from Mam’s fingers and fastened it around me neck. Not when I dug their graves with me hands and laid them there together beneath the hawthorn tree. Not when I took the boots from Mam’s feet and pulled them on me own. Not even when I covered the two of them over with the stones.

At once, the memory flips me sadness to wrath, and I nearly scream. I think of Da’s words: “Meter your temper, Mary. Me mother was an O’Brien. The O’Briens have Banshee blood. Save your rage for those who deserve it.”

These dear people do not deserve it.

The cart is quiet for a time. I think we all are deep in our own memories, but then, Tim says, “You walked all the way from Kinsale? That’s at least thirty miles from where you fell.”

“I’d have made it the whole way, but, once down, I couldn’t wake up. I’d have died for sure if you hadn’t come upon me.”

Moira climbs into the back of the cart and wraps her arms tight around me shoulders. “Ah, love,” she croons, rocking me like a báibin. The kindness of her touch nearly sets me weeping again, but I set me jaw tight as a badger trap.

She taps the man on his shoulder. “Tim, give me a bit of that bread and the water jug. The child is starved to bone.”

When she hands me the bread, I try to chew slow. Mam said you could pick out a lady from a shanty girl by the way she ate. But the hunger makes me swallow too fast, and the bread sticks in me throat. I hiccough like a common drunkard. “Excuse me, please. I ate too quickly.”

“That’s all right, Mary. You’re hungry. The good Lord sent us to help you,” she answers. “Things will be better now.”

I lean back against her. Her arms feel good, almost like Mam’s. “What was your village?” I ask, and then take a swig from the water jug, careful not to let it dribble down me chin.

“Killarney,” she says. “We held on through the first year, but when the potatoes came up black again, we couldn’t produce our quota of grain. It was only a matter of time ’til our cottage would be ashes.

“We’ve booked tickets on the Sheridan, a ship headed for New York. Cost us dear, four pounds each, British sterling. It’s all we had left. We sail tomorrow.” She turns me around and looks deep into me eyes. It’s as if she’s looking for me soul itself. “What ticket did you book?” she asks.

Can I trust her with the truth? Will they put me back on the road if they know I haven’t a farthing in me boot, let alone money for a ticket? I decide on a half lie. “I haven’t a ticket yet, ma’am. I plan to buy one at the wharf.”

Her face goes dark. “Are you sure you have ticket money, Mary?”

“Sure I do,” I lie all the way this time. “I saved it from what me da got for the boat.” She needn’t know that all I have in me pocket is a toothbrush. I haven’t reckoned yet how I’ll get on a ship. I’ll figure that out once I get to Cobh or whatever they’re calling it now. What did she say? Queenstown? No matter.

She lifts me hair off me face and twirls it around her fingers. “Lord God, your hair must be lovely when it’s clean. Such a pretty shade of red and so curly. You’re going to be a beauty when you grow up.”

I feel heat rising all the way up to me scalp, likely turning me face the fiery crimson I hate. Compliments embarrass me. Da used to say I have the coloring of a Celtic goddess to make me blush. I know how I look, too tall for me frame, too scrawny, too pale, and all of it topped off with crazy red hair spiraling around me head like the Banshee herself. That’s what Siobhan used to call me when she got mad at me – Banshee girl. All the blather in the world can’t turn me pretty.

“Ah, that’s just blarney, missus,” I tell her. “Me mam was the pretty one, and the baby, too. Their hair was black as midnight and their eyes blue as the River Shannon itself. Honestly, when you touched their skin, it felt like flower petals. I’m white as that stupid goat there,” I saying, pointing to one in a field we’re passing. “Mam and Ellen were plump and soft before the hunger wasted them. I’ve always been bony like a skeleton, the gránna one of me kin.”

“You’re wrong, Mary,” she says. “You will be a great beauty.”

I shake me head and fake a grin. “Nah, I’m the strong one. Da taught me to ride the horse faster and shoot a pistol straighter than any boy in Kinsale. I could out wrestle them, too.

“Mam always said to the neighbors, ‘Ah, look at me Mary, will you? Láidir, she is. She has the strength of the son I never had.’ She was right. I am strong and faster than any of the lads in me village. I won all the races.”

Moira laughs out loud. “I wager you’re right at that. You must be strong and fast. Look how far you got before you fell.”

I nestle me cheek against the soft flannel covering her shoulder and gaze at the sun lighting the whitecaps of the Irish Sea. I’ve loved this land since me birth, and grief at leaving it nearly takes me over. But this blossoming countryside is fake as a leprechaun’s kiss. The glory of Ireland was fashioned by the devil’s hand, not God’s.

So I sit up and stiffen me neck. Touching Mam’s cross, I remember me pledge to her. I will get on a ship. I will find Da. I will go to a land where food grows plentiful. Ireland is a place of death, not plenty. I will not falter.

“Don’t be so strong you make all the boys run from you, Mary,” Moira says. “Someday, you’ll want to marry, you know.”

“Oh, not me, Moira,” I say, stammering the name even as I say it. “I’ll not marry, ever. That’s what I told me friend, Siobhan, before she sailed off to Australia with her family. Siobhan was always picking one lad or another to be her husband when she got grown. But when she asked me who I would marry, me answer was always the same: no one.”

“You’ll change your mind when the right one shows his face,” Moira says.

Let her think what she wants. I know what goes on between a man and wife. Our cottage was one room after all. In the dark of night, I heard what me parents did when they thought me sleeping. Nothing of that sounded like something I’d fancy. Of course, I can’t say that to the Mrs. Donahue. Such talk would be a scandal.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.