Ann Miller Woodford is many things, but one thing she’s admittedly not is “a data person.” Instead of making sense of the world through statistics, the Andrews-based artist, author and activist takes creative approaches and shares them through paintings, books, public speaking and other actions that focus on racial justice and equity.

This commitment dovetails nicely with her involvement in the multiyear Heart of Health: Race, Place and Faith in Western North Carolina project, which approaches those topics from a social science standpoint. Together, Woodford and colleagues created Black in Black on Black: Making the Invisible Visible, an exhibit that pairs area artists’ work with the research team’s findings, resulting in a stunning, well-rounded experience that grants greater meaning to each component.

The collaborative project opened Sept. 6 in the John Cram Partner Gallery at the Center for Craft and will be on display through the first week of January. The selected artwork and the study’s key findings are viewable online and will soon be joined by a virtual tour by Saturday, Nov. 6, in time for UNC Asheville’s African Americans in Western North Carolina and Southern Appalachia conference.

More than a statistic

In 2019, Ameena Batada, UNCA professor of health and wellness; JéWana Grier-McEachin, executive director of the Asheville Buncombe Institute of Parity Achievement; and Jill Fromewick, a research scientist at the Mountain Area Health Education Center, were awarded a three-year, $350,000 Interdisciplinary Research Leaders fellowship from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Together, they set out to explore rural African Americans’ perceptions of racism and health, and investigate the association between racism and health outcomes. Helping steer their research was a community advisory board composed of 10 individuals, mostly African American, from across Western North Carolina, representing a variety of professional expertise and experience.

According to Batada, the study has three main components. The team conducted a secondary data analysis, in which they worked with a statistician to understand mortality in the region and across North Carolina, as well as the difference between rural and urban populations, particularly African American. They also did historical and archival research, consulting U.S. census data beginning in the late 1700s to gauge the percentage of WNC’s African American population over time, as well as government data regarding social determinants of health, utilization of health care and related matters for that particular community.

“And then the last part of it was interviews that we did and oral history coding,” Batada says, referring to the way people answer questions rather than what they say. “We tried to complement the quantitative data with qualitative data and use story data to help bring more richness to those numbers. Nobody wants to be simply a stat, so that was really important to us.”

Woodford, author of When All God’s Children Get Together: A Celebration of the Lives and Music of African American People in Far Western North Carolina, is among the advisory board members.

“They reached out to me because they wanted to find out what I know about the African American people and the disparities in health and disparities all over that we have in this region,” Woodford says. “They consider me a mentor to the group, and I go out and talk with people and try to bring back the information.”

Through the project, Woodford was reminded that people of all skin colors in the far western part of the state are notoriously private and don’t like to speak about their health. “It’s difficult to help them if they won’t talk, but we’ll continue to try,” she says. “After the project is finished at end of the year, we’ll continue to keep doing as much research as we can.”

According to Batada, the study’s key findings are that data on Black and African American populations is fairly limited in WNC, particularly in the more rural counties. And when data is available, racial inequities exist across everything from health outcomes to such determinants as owner-occupied households and the prevalence of Black farmers compared to the overall population.

“Despite this apparent invisibility, there are really rich stories of the contributions that Black and African American populations are making in this region — but you have to pay attention,” Batada says. “And [these populations] need to be integrated into the public health and health care systems, so that that community is also prioritized.”

The complete picture

Working with Woodford and fellow artists Ronda Birtha and Viola Spells, the Heart of Health team saw the potential to have their research reach a greater audience through the power of art — a mindset sparked by one of Woodford’s oil paintings.

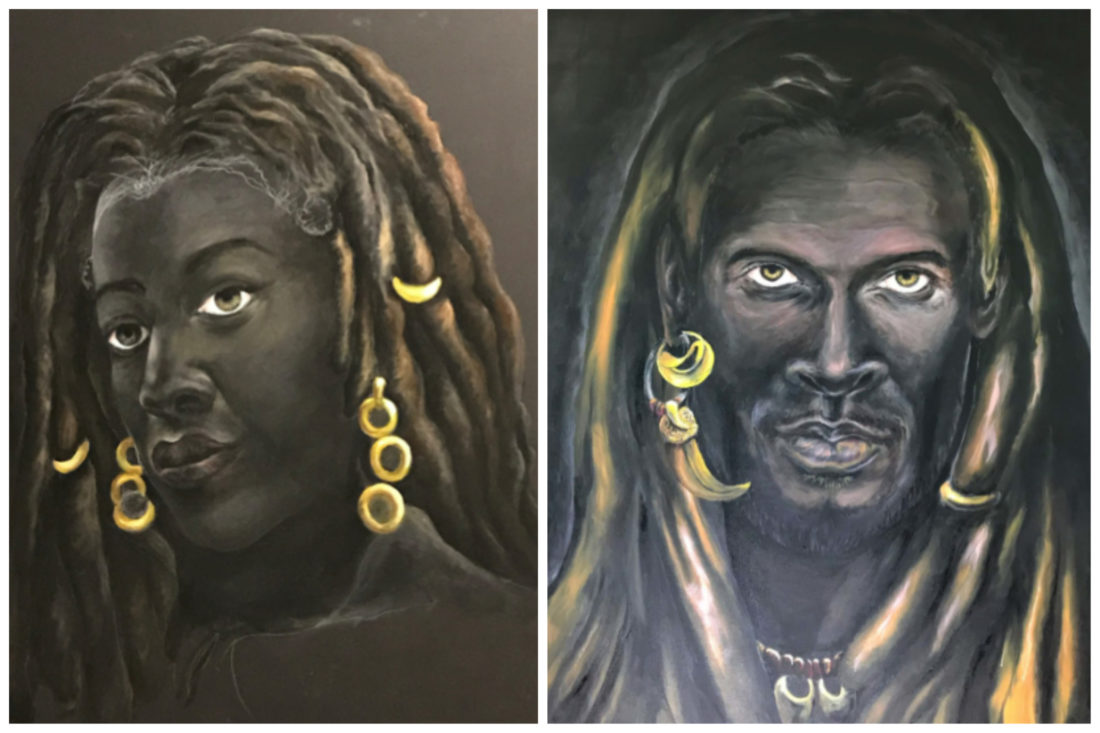

“It really started when we saw ‘Queen,’” Grier-McEachin says. “The art was just so striking, and ‘Queen’ is the opposite of invisibility.”

Just as the people in Woodford’s paintings turn their gaze back on the viewer, Batada feels that Birtha’s conversational photographs — which include Woodford’s late father, Purel Miller — invite onlookers into the subjects’ homes. She adds that Spells’ jewelry and sculptural pieces likewise exude a distinct, tangible history that sheds light on long-held African American artistic traditions.

As for the exhibit’s title, Black in Black on Black is also the name of Woodford’s recent series of paintings, which the artist says is about African American people emerging out of darkness after a long period of reserved behavior.

“People say, ‘I don’t see color,’ and they mean something good by that. They mean to say that they’re looking at people as people, but it’s not a good thing to say,” Woodford says. “I always try to be sure to let them know, ‘Don’t say that, because that means I’m invisible. If you don’t see me, if you can’t see me, then you don’t see a person. You don’t see my heart, my spirit, my love, my care for the community.’ So that is very important.”

Asheville-based artist Reggie Tidwell tied the various pieces and research together with his design work, and upon seeing the complete exhibit, the Heart of Health team experienced an epiphany regarding how to share data.

“As a researcher, I feel more accountable and challenged to ensure that my research is relevant and makes a difference in some way,” Batada says. “One of the things that people who come to the exhibit have been telling me, especially my colleagues at UNCA, is that this is such a wonderful way to make research findings tangible, understandable and relatable to people who don’t read and use research on a daily basis.”

Grier-McEachin likewise witnessed the power of this presentation on the public. “It was interesting to see an intergenerational appreciation for the exhibit,” she says. “During opening night, there were older people, but there were also teenagers who came through and were able to talk with the artists and have meaningful conversations with them.”

All three artists and the three researchers will take part in a guided virtual tour of the exhibition and a panel discussion on Wednesday, Nov. 10, 6-8 p.m. Once Black in Black on Black ends its run at the Center for Craft, Woodford says it will be moved to the Mountain Heritage Center at Western Carolina University for a few months. After that, it will likely find a home at a few other locations across the area, and she plans to add new work for these subsequent moves.

“I’ve had people up in Highlands and at Mars Hill [University] and different places like that asking me about displaying,” Woodford says. “I have to paint seriously so I’ll have some work for them.”

WHAT: Black in Black on Black: Making the Invisible Visible

WHERE: Center for Craft, 67 Broadway. avl.mx/ajd

WHEN: Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.- 6 p.m., through Jan. 7

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.