“One of my big guilty pleasures is true-crime stuff,” says John Garland Wells. “But the way they describe [the details] on podcasts and on those TV shows that Netflix puts out every 10 minutes is very clinical — to the point where it sounds kind of exploitative.”

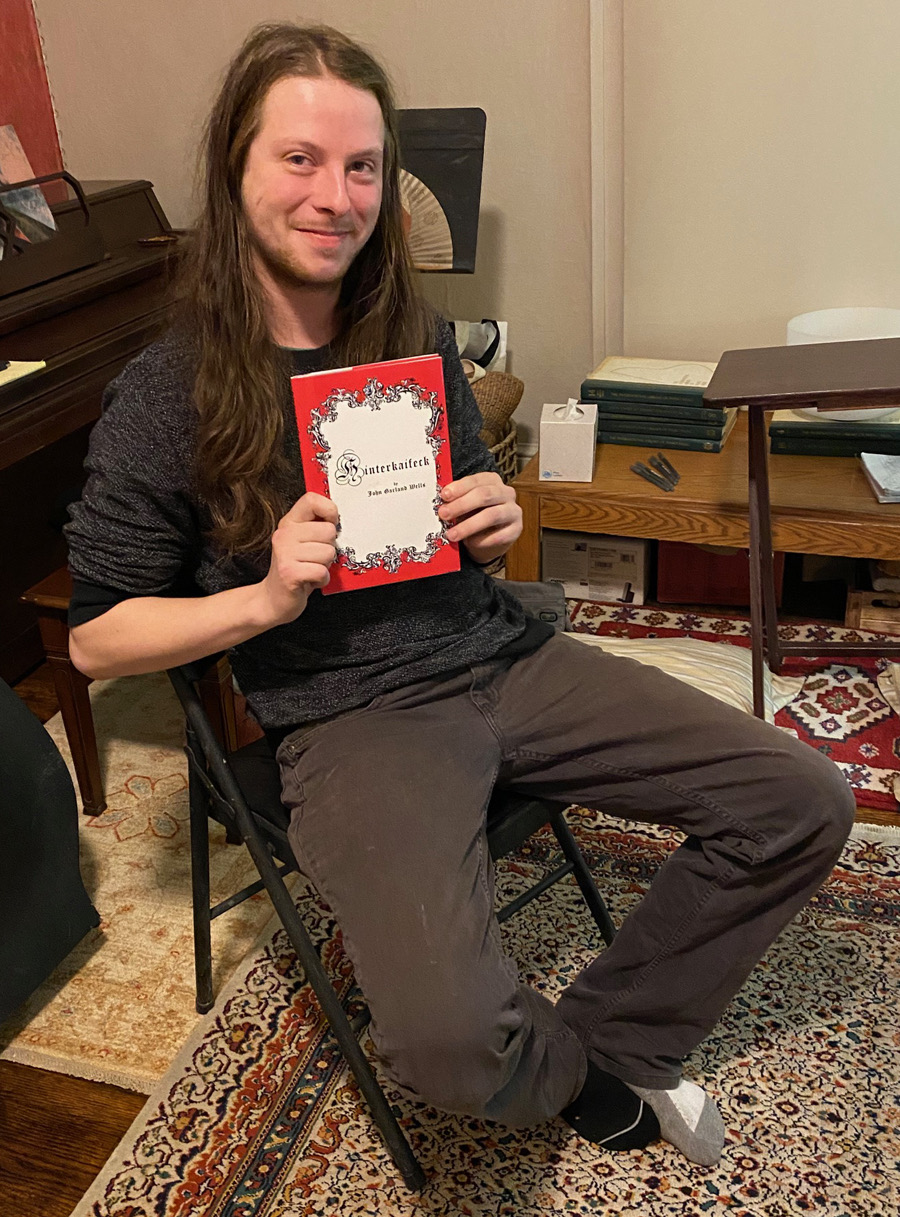

The Asheville-based author avoids such trappings in his novella Hinterkaifeck, which uses prose poetry to tell the still-unsolved 1922 murder of the Gruber family in rural Bavaria.

Wells first heard about the case on the “Generation Why” true-crime podcast in October 2015. Hosts Aaron Habel and Justin Evans started their program in 2012 — two years before the launch of Sarah Koenig’s “Serial,” which is often cited at the first major true-crime podcast.

On March 31, 1922, farmers Cäzilia and Andreas Gruber, their daughter Viktoria, two young grandchildren and servant Maria Baumgartner were murdered with a mattock. The intruder then stayed on for three days to keep a fire going, attend to the animals and generally make passersby think that the Grubers were still alive.

“I like that kind of psychological, human-horror stuff,” Wells says. “So I kind of went down a rabbit hole and felt like I could apply my sensibilities to this superdark story and flesh it out.”

The combination of an isolated German setting in a snowy winter gave the story “a dark fairy tale aspect,” says Wells. But little did he know that in undertaking the project, a journey awaited.

Mind hunter

Since the crime remains unsolved and theories abound regarding the killer’s identity, Wells traced each possibility to see which one resonated most with him. Over the course of seven months, he read multiple books on the case and — with help from Google Translate — German magazine articles that feature interviews with multiple generations of families based in the surrounding villages.

“I wanted to get a little bit of insight into how [the murders are] viewed amongst the people that live near that place and how that had changed over the years,” Wells says. “They kind of tell it like a boogeyman story — except it’s real.”

Wells also watched several documentaries on YouTube but stayed away from self-published works by what he calls fellow “armchair detectives.” Instead, he sought out peer-reviewed articles.

“They’ll interview forensic psychologists about what kind of person would do this,” Wells says. “With [my] book, I wanted to take on each different persona of the people involved, and I wanted to at least be somewhat on track with how that could have looked — their inner psychology.”

Wells ended up landing on the idea that neighbor Lorenz Schlittenbauer was probably having an affair with Viktoria Gruber and fathered her 2-year-old son, Josef. The proximity to his child likely drove Schlittenbauer to kill, as did rumors that Josef was the product of incest between Viktoria and her father.

“It was kind of like the darkest, real-life soap opera you can imagine — and I’m kind of sucked into trash TV,” he says. “Those melodramatic relationships I thought were supercool.”

Body count

Wells has enjoyed a prolific creative output through his self-described “punk-poetry band” Bad Ties. But other than his 2021 debut novel, Maxie Collins Dreams in Wretched Colors: A Story of Murder in Poems, he often struggles with longer works.

“Part of the problem I’ve had with being a younger writer is getting halfway through something that I’ve completely made up and then finding it’s hard to figure out where I’m going with it,” says the 26-year-old.

The Grubers’ story presented him with an appealing writing exercise: Wells had the basic details of the event — “a skeleton of facts that you can fill in the gaps with your own imagination,” as he calls it.

“I thought it had a lot of potential to still stick to a through line — just the beginning, the middle, the end — but at the same time being able to apply my own thing to it,” he says. “[Hinterkaifeck] is loosely based on a true story. I would never say they should read this in, like, a forensic crime class, you know?”

With help from the peer-reviewed articles, Wells added personal details for each family member and explored what he calls their “weird dynamic” through poetic inner monologues, capturing their mindsets leading up to and during the grisly incidents. He also inhabits the unknown assailant, whom he dubs The Phantom, and describes the figure in a chilling, detached manner.

Initially, Wells envisioned the work as a novel wherein each chapter was told by a different character, similar to George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series. But he soon abandoned that plan.

“I realized at a certain point that when you write a novel, it’s all about concrete detail. You want to put in all of these specific details: What were they wearing? What did it smell like? All this stuff. And, to be honest, I thought, ‘Well, I don’t know if I have enough to fill 200-300 pages of that,” Wells says.

“For one, it’s pretty unpleasant. It’s a big ask … to get someone to read 300 pages of absolute misery and these kind of perverse dynamics.”

Wells then considered going in the opposite direction and presenting the tale in poetry chapbook form. But he decided that 35 pages — the typical length of such publications — was too short.

“I wanted to get more than just the crime,” he says. “Otherwise, it’s just torture porn in the form of a poem.”

Gather ’round

Landing somewhere in the middle of those two options, Wells told the tale as a long poem. And though he was generally satisfied with the novella’s progress, finding the proper framing device eluded him.

After a few drafts, it dawned on him that his poetry style came across almost like someone telling a dark lullaby — one with significant repetition. And being a longtime movie fan, a vision worthy of the big screen soon appeared in his mind.

“I had this cinematic image of this old woman by the fire and her wrinkles being illuminated with the flicker of the fire. And all these people kind of coddling around her and she tells them the darkest story they’ve ever heard in their whole life — this haunting memory that she has,” Wells says.

“I like that idea that it would be passed down with oral tradition in these taverns. And also the wicked irony of going into a tavern to get warm and hearing this really cold story from this old woman.”

Wells then sent the finished tale off to multiple publishers and Portland, Ore.-based Corpolailiac Press agreed to put it out. The author notes that it was the publisher’s idea to include original artwork and photos from the crime scene “to break it up so it’s more immersive and not just one long train into the dark.”

Speaking of transportation, Wells describes himself as “an aspiring dark tourist” who’s fascinated by the prospect of visiting places with tragic histories. When he was a teenager, he told his parents he wanted to join the Peace Corps so that he could go to the site of the Jonestown massacre in Guyana — which he admits is “so morbid and ridiculous.” But he would love to eventually visit Hinterkaifeck.

“If I ever went, I would probably update the book,” Wells says. “I think the publisher would be down to do revisions or a little postscript.”

To learn more, visit avl.mx/dc7.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.