The rock musical is something which, some diehard fans of musical theater might argue, is an unforgivable invention — an attempt at “updating” the form so it might be palatable to a more mainstream and younger audience. The Who’s Tommy, of course, was the first major benchmark of the form. Then Rent came along in the ‘90s, touching on all manner of buzz themes for the MTV generation, from suffering for your art to the AIDS crisis, to running away from the concrete jungle for more attractive prospects out west (though instead of romanticizing supposed ‘90s utopia Seattle, it turned its starry eyes to Santa Fe for a few numbers).

Now, we have Hedwig and the Angry Inch to thank for keeping the rock musical alive. But, where Rent often chose schmaltz over actual rock ‘n’ roll danger (“How do you measure a year? How about love?” isn’t quite a fist-pumping rock ‘n’ roll declaration), Hedwig makes it clear from the beginning that the production is going to go there. Whether bemoaning a “botched” sex-change operation, dropping one-liners only a drag queen can typically get away with (“When it comes to huge openings, a lot of people think of me”) or throwing temper tantrums accompanied by distorted guitars wherein the star rips at her own sexual identity, there’s not a lot of safe schmaltz in this production.

That N.C. Stage has chosen this of all shows with which to celebrate its tenth year, is a statement in itself. Indeed, Hedwig was the company’s first-ever show when its doors first flung open in 2002. Its revival a decade later speaks not only to the theater’s continuing commitment to envelope-pushing material, but also to its refusal to become dated in doing so. Where Tommy and Rent are very much of their eras, there’s something a little more timeless about Hedwig.

In this case, the title role as performed by Michael Sheldon (perhaps best known locally as the late Cookie LaRue) pulls no punches. Sheldon’s presence in character alternates between a stumble and a swagger — some kickass combination of Cher and Johnny Rotten. Despite his years performing in drag, his Hedwig doesn’t come off like a drag queen so much as … well, a bitter old German lady whose sex-change operation went awry.

Behind her, the band sits perfectly in character without upstaging their star. Drummer Caleb Beissert wears his role best, eschewing the dreaded drummer face to look instead like a character from the Rock Band video game. Guitarists Matthew Kinne and Aaron Price swap solos swimmingly and bassist/N.C. Stage co-founder Charlie Flynn McIver holds down the foundation with a little bit of an asshole meathead vibe, all the while chewing on a lollipop stick. Rock ‘n’ roll.

If this production has any snags, though, they’re in the inconsistency of Hedwig’s German accent (which falls off somewhere during the opening monologue and returns throughout the show only in spurts), and the questionable believability of Laine Lewis as Yitzhak. To be sure, Lewis’s contributions as a backing vocalist are superb, but her drag king presence is made less convincing by the sheer fact she’s playing opposite Sheldon’s more spot-on Hedwig. Yitzhak’s saving grace is that he spends the production sporting a T-shirt from Rent — a wink-and-nudge hat-tip to the safer, more explicitly sentimental musical. Either it’s an attempt to further portray how solidly he’s stuck in the past, or the costume decision was intended as an inside joke about that musical’s cultlike collection of fans. (Maybe a little of both?)

Though themes here range from love to the pitfalls of Communism, in the end this is a show about the things which define an individual. The script walks the fine line between what others see and what we see of ourselves, searching for the ways in which those two things intersect. Sheldon’s Hedwig embodies both these perceptions, eventually opting to focus more on “what [she has] to work with” than whatever might make sense to others. Ripping off the be-fringed fashion, the wigs and the false breasts, Hedwig seems to resolve what she is underneath is all that matters. Her rage and bitterness combine for an empowered flavor of resignation which is happy to let others be who they are, as well.

Maybe that sounds like the kind of contrived schmaltz one might expect from a rock musical, but it comes off as more of a punk-rock transformation. Like David Bowie trading in the catsuits and capes for a black trench coat and jeans. Perhaps what makes Hedwig such a gem is its decisive refusal to be anything other than what it is. It’s not trying to fit the Broadway mold; instead, it simply tells the story of one woman coming to find herself, amidst the madness of all the people who have “come upon” her.

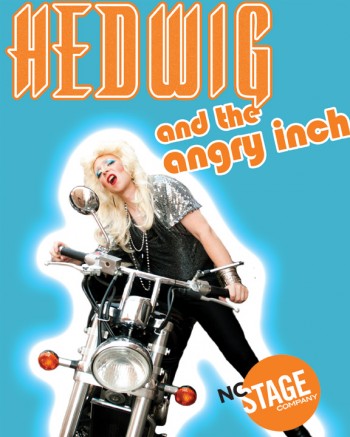

Photo by Jen Lepkowski

Your reviewer states, re rock musicals, “‘The Who

There’s also ‘The Tooth of Crime,’ a musical play written by Sam Shepard which made its premiere in London’s Open Space Theatre on July 17, 1972. It was also recognized in 2006 for a production at LaMama E.T.C. (La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club)in New York and there were many productions in between those years.