When Asheville resident Todd Stimson was released from Foothills Correctional Center in April, he had one request: that his family prepare his favorite meal, London broil marinated in Speidie sauce, skewered and cooked over an open fire. The sauce brings back memories of his Italian family, he says — memories that seemed very far away while he served a two-year prison sentence in a facility near Morganton.

For the duration of his sentence, Stimson’s diet included foods like chicken patties, cereal, canned vegetables and a morning glass of juice made from concentrate. For several months, he worked as head kitchen employee, which gave him a firsthand look at the food entering and leaving the prison.

“All that stuff is still fresh in my mind, believe me,” Stimson says. “They say that it does meet the nutritional guidelines, but the amount that they give you doesn’t add up to the amount that you’re supposed to have. They have the standard charts and everything like that, but the food is just not what they portray it to be.”

As the nation’s prison system is increasingly scrutinized, incarceration has become synonymous with a dismal perception of prison food. “A lot of people look at prisons in a lot of different ways. And we don’t get lots of positive feedback — just think about what you’ve seen on the news or read lately. Prisons get a bad rap,” says Marty Galloway, Craggy Correctional Center superintendent. “But it’s really not like that. Food service is one of the parts of this facility that’s on an even keel. For a prison this size, that’s good.”

Comparing calories and nutritional guidelines

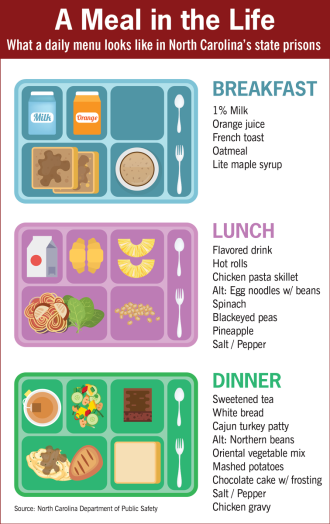

At the state level, food production and distribution within the prisons are down to a science, says Kelli Harris, state food and nutrition management director. Three times a year, registered dietitians write a five-week menu consisting of three meals a day, which is then sent to each of the 55 North Carolina prisons via computer program.

“We try to make everything as standardized as possible,” Harris says. “If they’re getting grilled cheese sandwiches in the west, they’re getting grilled cheese sandwiches in the east. Everyone in the state uses the same recipes, so the food should taste the same at Craggy Correctional Center in the mountains as it does as Pasquotank Correctional Institute on the coast.”

Just north of Asheville stands the Craggy Correctional Center, a state prison facility that houses just under 600 medium- and minimum-security inmates. Every week, a truck brings fresh produce to the facility; every two weeks sees the arrival of meat products or dry goods on a rotation — like clockwork, says Wayne Fish, Craggy Correctional food service manager.

Following the Dietary Reference Intakes published by the Institute of Medicine, a regular prison diet at state facilities consists of 2,700 to 3,000 calories a day, administered with no more than 14 hours in between meals, Harris says. Additionally, physicians can recommend therapeutic diets for a variety of medical conditions, inmates can request specialized menus for religious practices, and a vegetarian option is also available at every meal.

“We cook basic, from-scratch cooking, not a premade item that you take out and heat it up like you see in a lot of restaurants now,” Fish says. “Our food is very basic, true cooking from scratch, and basic is healthy. The less processed the item is, the better off you are, and that’s the case that the state is making.”

The Buncombe County Detention Facility tries to meet similar expectations. While the average length of stay is much shorter and the menus rotate on a two-week cycle, dietary needs comply with nutritional guidelines set by the state, says Tony Gould, projects lieutenant for Buncombe County. The regular diet at the county jail consists of 2,100 to 2,500 calories a day and includes two servings of dairy, two servings of meats or proteins, three servings of vegetables, a citrus fruit and an additional fruit serving and four servings of whole grains, according to the N.C. Administrative Code.

“I think we do a very good job with what we do,” says Gould. “When you’re looking at on average over 500 inmates getting three meals a day, it’s a challenge to make sure everyone is getting what they need, but one we take very seriously.”

Both facilities strictly regulate portion sizes as stated in the dietary menus — a move that tends to generate the most complaints, Gould says, but is necessary to meet the state guidelines. “People are often used to big home-cooked meals made by their families; if their mom cooks them a huge bowl of spaghetti every day, an 8-ounce serving might seem tiny.”

The cost of contracts

It currently costs an average of 72 cents to provide one meal at the Buncombe County Detention Facility, Gould says. At a state facility, the cost of one meal averages between 90 and 95 cents, according to Harris.

“We try and mix things up so it’s not the same every day, but if we’re buying food, it’s easier and cheaper to buy it in bulk and use it a few times throughout the week,” Gould explains. “We’re looking to get the best deal — it’s like going to Ingles and getting the extra money off when you use your Advantage Card. If we could get a little more food to serve for a little less money, we will.”

In Buncombe County, the jail’s expenditures are funded by the county’s operating budget, and food contracts are filled by multiple providers: Reinhart Foods, US Foods, Performance Foods, JMJ Tomato and Asheville Packing. In contrast, the state prisons operate under a sole contractor, Correction Enterprises, which trains and employs inmates in hirable skills, says director Karen Brown. With a 7,300-acre farm, a meat processing plant and sites to inspect and distribute fresh produce and other pass-through items, Correction Enterprises works closely with Harris and the state dietitians to cultivate and harvest the crops needed for the rotating menus.

“Say [Harris] wants collard greens versus some other type of green for a new menu. We work with her about what she wants and what she’s going to put on her menu, and that’s what we grow and plant,” Brown says. “For example, we started harvesting sweet corn last Monday — part of that will go to the prisons fresh, and the other part of it will be canned for later utilization.”

Sodas, chips and candy

Each of the state prisons, as well as the Buncombe County Detention Center, has an on-site commissary, or canteen, so inmates can purchase additional items not provided by the facility, including supplemental snacks and drinks. Starting July 1, North Carolina commissary prices increased from an 18 percent price markup to a 20 percent markup, says Charles Brooks, corrections sergeant fiscal at Craggy.

State inmates work wage division jobs and are paid between 70 cents and $1 a day, Galloway says, and that money is applied to canteen purchases. Family members are able to send additional funds to inmates, but Brooks explains that he tries to keep the canteen stocked with low-cost items such as crackers and candy. “The big thing down here is that one guy will buy the noodles, one guy will buy the wraps, and at the end of the night, they’ll cook it all up and make a burrito,” he says.

The extra revenue from state commissary purchases goes into a statewide welfare fund to purchase communal items not funded in the regular prison budget, Brooks says. At Craggy, the welfare fund allowed for the purchase of basketballs, televisions, microwaves and water coolers in the housing units.

During his stay at Foothills Correctional Center, Stimson says the canteen served as a way to bypass bad meals in the dining hall but unfairly limited those who couldn’t pay for an alternative. “There was no way to get anything nutritious from the canteen, like sandwiches or fruit,” he says. “Sometimes the stuff would be expired, and a lot of times the canteens would run out of things because they only order things once a week. The biggest thing that people would buy would be protein bars, but the protein bars cost so much. If you don’t have family members sending you money, it’s really hard.”

Grievances, feedback and changes

Looking back over his time in the kitchen at Foothills, Stimson recalls chewing on chicken patties and finding remnants of bones, being fed pancakes made with salt instead of sugar, a yearlong period without having eggs with breakfast and warnings on the labels of the juice concentrate used at breakfast that the mix could be toxic for human consumption. Most concerning, he says, was the fact that they were told a month in advance what day the prison’s health inspection would take place — and they would work overtime to clean mold off the walls and reseal the floors just to pass, he says.

Requests to speak with current inmates at both Craggy Correctional Center and the Buncombe County Detention Center were denied. Xpress did attempt to reach former inmates on social media, garnering comments citing small portion sizes and overall bad tastes.

Both positive and negative feedback is received regarding the county jail’s food, Gould says, all of which is taken into consideration for improvement. “No system is ever perfect, and of course there are always some things we could do differently. But we try and make it the best we can, to make their stay positive. They’re people too.”

At Craggy, Fish believes that food service is one of the strongest aspects of the prison. “The inmates, they do a very good meal because they have to live with the other inmates — there’s peer pressure,” he says. Galloway echoed his agreement: As superintendent, he says he only gets five to 10 complaints a year. “Food service is the one thing that we do right. If you keep them fed, you keep them happy.”

Prison food is trash. Aramark in Ohio is the WORST! GOOGLE it been there done that

I am appalled always that a group of people who are in charge of another’s incarceration can warrant abuse! The thought of feeding a person on 97 cent’s a day is absurd! This is America, at it’s worst! Good grief! Who do I petition and why doesn’t everyone know? Ty

I want the chicken pasta skillet recipe..

talk as if offenders get fresh food everyday, ‘NOT SO’