During the summer of 2009, Ann Batchelder took a breather between curating an exhibit for the Asheville Art Museum and launching a consulting business. Her son was in college and her daughter, Olivia, was entering her junior year in high school. All seemed well. Then, her vision of her life suddenly skewed as if she’d been peering into a kaleidoscope: Olivia revealed in a raw and tearful confession to her mother that she was suffering from an eating disorder, depression and suicidal thoughts.

Batchelder knew adolescence is challenging for most young adults. She also knew the specific difficulties her daughter had experienced finding her path and people in high school. Still, Batchelder’s first reaction to Olivia’s mental health struggles may be familiar to many mothers: She blamed herself.

“There is so much pressure in our society for mothers to be perfect, and I thought I was doing everything I needed to do to be a good mom,” Batchelder explains. “So, when she got depressed in high school, I wondered if it was my fault, what did I do wrong, what should I have done differently. Was I too much or not enough?”

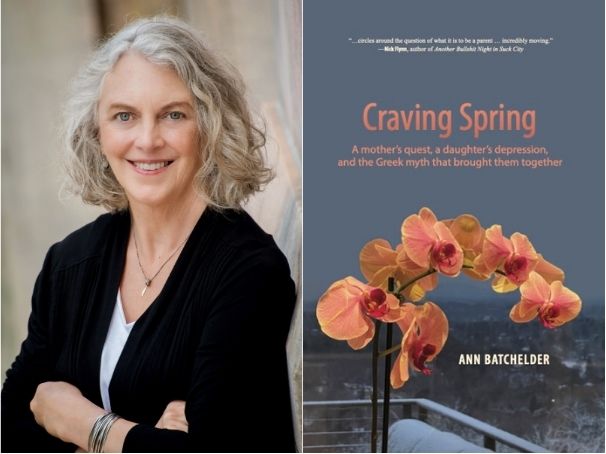

In her memoir, Craving Spring: A Mother’s Quest, a Daughter’s Depression and the Greek Myth That Brought Them Together, which Legacy Book Press published in August, Batchelder weaves together journal entries, hard-earned insights from her life and a Greek myth for an insightful story of resilience and hope when a child is in crisis.

“Craving Spring is one woman’s journey through her daughter’s depression, but really, it’s a book about self-discovery, trying to understand what happened in my family, what my role in it was and what I needed to change in order to move forward and return to myself,” she says.

Persephone and Demeter

After Olivia’s confession, Batchelder sought professional help from an adolescent psychiatrist and eating disorder specialist for her daughter and a therapist for herself. During one session in which they discussed Batchelder’s ceaseless worry about her daughter, her therapist spoke of a Greek goddess who became a guiding light for Batchelder’s own way forward. “She said, ‘You sound like Demeter,’” she recalls. “I said, ‘Who?'”

A brief refresher of Greek mythology: Demeter, the goddess of the harvest and agriculture, was the mother of Persephone, the goddess of spring. One day, despite being forbidden by her mother to play in the verdant meadows unaccompanied, Persephone wandered away from her friends in search of more wildflowers. The god Hades snatched Persephone and pulled her down to the underworld to be his bride. Demeter went insane with grief and fear, desperate to save her daughter, and neglected her duties as the goddess of the harvest. To quell her mother’s fears, Persephone would return to Demeter but only for half the year. According to the myth, this arrangement is why Earth has seasons.

“At first, I didn’t dive any deeper into it than that,” Batchelder explains. “All I cared about was I had a role model who went crazy when her kid was in trouble, and that kind of validated me. But when I read more, I started thinking about the parallels in my life. It helped me accept myself and have compassion for myself as a mother.” The story of Demeter and Persephone guided Batchelder in her transition from feeling paralyzed with terror and anxiety to accepting that Olivia was on her own recovery path. That adjustment proved invaluable when her daughter subsequently grappled with substance abuse and addiction.

Batchelder learned to accept that while it is natural for a mother to worry, it wasn’t productive or helpful for Olivia. “When I recognized I was not powerful enough to control my daughter’s recovery, that’s when I had to compromise to allow her to have her own recovery,” she explains. “That is extremely hard. I had to transition from thinking I could somehow protect her from pain to supporting her in her own process.”

In addition to therapy and Greek myths, Batchelder also sought support from Al-Anon and Buddhist philosophy. In this vein, she learned to stop expending so much energy second-guessing and regretting the past because doing so meant she wasn’t being present in the moment. She explains, “The practice for me became trying to stay present and be the calm in the eye of the storm.”

Support system

Batchelder says she has always kept a journal, an exercise that she believes helps her process her life experiences. Journaling became increasingly important as she sought to understand what had happened in her family and why. She started taking writing classes at the Great Smokies Writing Program after her daughter left for college around 2012 and wrote some essays about her journey.

From 2020 onward, Batchelder concentrated on how a book based on these essays might take shape, and she developed a manuscript. She believes that examining the arc of her life, including how her own mother mothered her, and sharing that frank journey of self-discovery is most helpful to readers. “The point of the book is to have compassion for parents going through something similar and encourage them to not give up hope,” she says.

The isolation that a parent can feel when a child is struggling and the stigma attached to mental health and substance abuse issues can prevent people from sharing their experiences. Batchelder encourages mothers to find support from friends, family, therapy or faith. “Don’t allow yourself to become isolated, and don’t be afraid to be vulnerable,” she advises.

She also asked her daughter how she could have parented differently during the most difficult times. “She said what she wanted most for me was not to blame myself because that wasn’t at all helpful,” Batchelder says. “That’s what this book is about — how to transition out of that and into something healthier for me and for us.” Olivia gave her mother permission to write the memoir and contributed the epilogue. “What strengthened our relationship most was when she dropped the facade of trying to be the perfect mother and could be open and vulnerable with me,” Olivia wrote.

Batchelder hopes other mothers who read her memoir will reject the learned expectations of perfection, no matter what they face in their own and their children’s lives. “We have to allow for things not to work out and be able to pivot when that happens,” she says. “We have to trust in the fact that everything changes, and when things are good, they’ll get difficult again, and when they’re difficult, they’ll be good again. Like winter and spring, they come and go.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.