The last time Kevin Mahoney practiced social distancing, it wasn’t for his health.

“I isolated for two years and basically squatted in my own bombed-out house,” Mahoney recalls about the days when he was regularly using opioids. Now a peer support specialist for the Mountain Area Health Education Center, he hasn’t taken illegal drugs for over 15 years.

Despite the time that’s passed since he last used, Mahoney continues, stay-at-home orders to slow the spread of COVID-19 have still dredged up uncomfortable feelings. “When this started in March, I went, ‘Oh my God, I’m isolated. Nobody to talk to, no face-to-face.’ And my brain starts ruminating,” he explains.

Mahoney hears similar stories from the MAHEC medication-assisted treatment patients he helps with mental and behavioral wellness. Whether he talks with them by phone or in person (behind two layers of masks and gloves), those clients are sharing the strains that coronavirus-induced isolation and job loss have placed on their efforts to stay clean. “We’ve got an [opioid] epidemic within a pandemic,” he says.

Health experts paint a worrying picture of COVID-19’s danger to opioid users. According to Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the federal government’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, drug overdoses may have increased by as much as 40% in some areas since the start of the pandemic. And Amy Upham, Buncombe County’s opioid response coordinator, says emergency department visits for overdoses across North Carolina have gone up 18% from January to June.

So far, Upham says, Buncombe has avoided the worst of the pandemic’s effects. During the same period as the state’s recent increase in overdose ED visits, she points out, the county’s numbers have actually decreased 7%. But she stresses that the biggest impacts are likely still to come.

“Historically, looking at major disasters, economic depressions, pandemics, the height of the behavioral health issues like suicides and overdoses happens about six months after. That’s where it peaks,” Upham says. “We’re not there yet.”

Rapid rollout

Upham attributes much of the county’s relative success to the flexibility of its opioid treatment community. She explains that soon after COVID-19 came to Buncombe, county government set up a behavioral health workgroup that included MAHEC, Vaya Health, RHA Health Services and other partners to identify needs and coordinate responses.

One urgent need came from medication-assisted treatment patients who had lost jobs, and the associated health insurance they had used to pay for care, due to the pandemic. Upham says the county worked quickly with MAHEC and the Appalachian Mountain Community Health Centers to fund suboxone treatment for 11 such patients through a federal grant. Buncombe also connected the Asheville Comprehensive Treatment Center with state funds to help uninsured, unemployed patients continue methadone treatment on the same day that grant money became available.

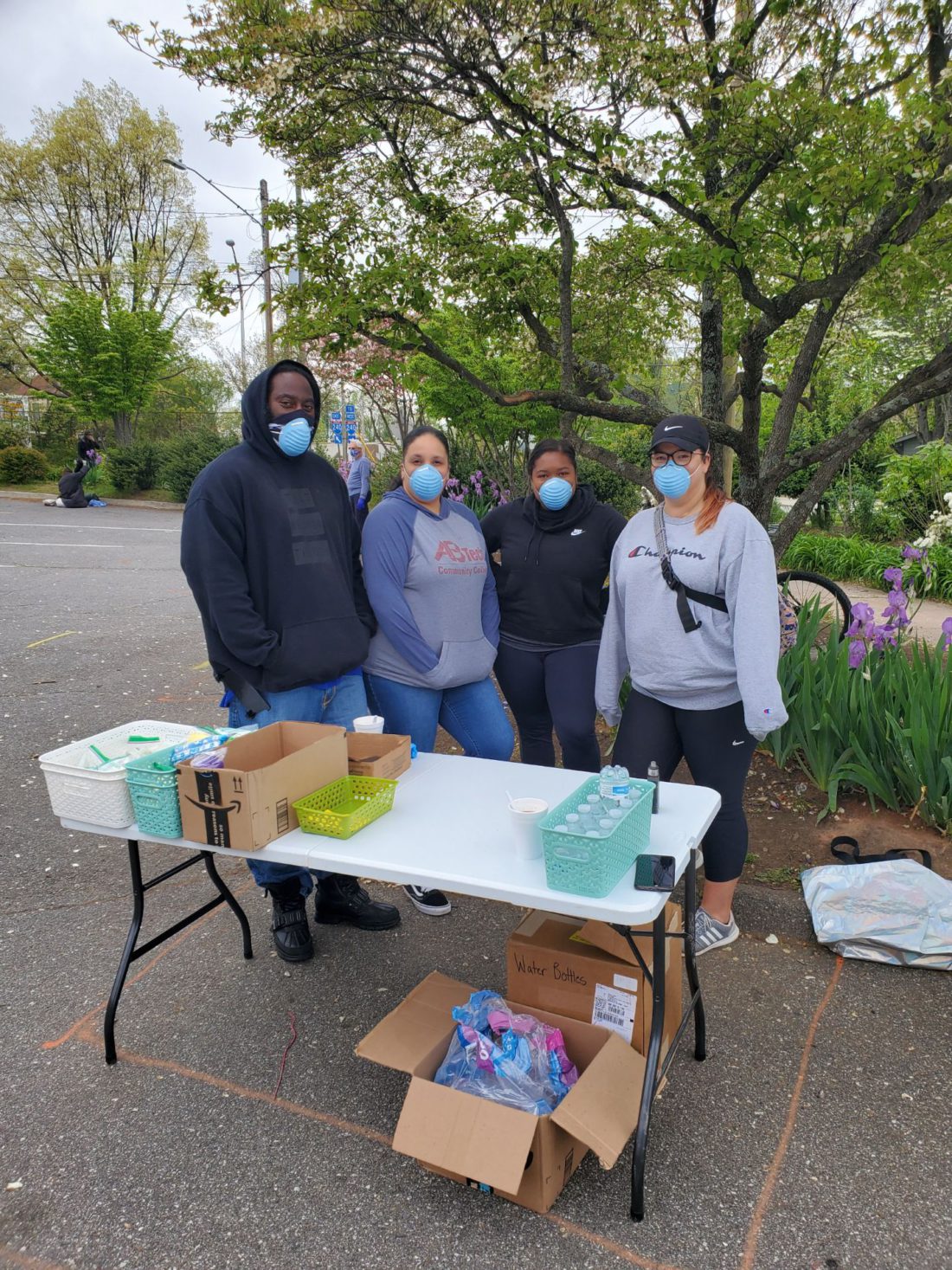

Under emergency state authorization, Upham continues, county staff members began distributing syringes and other supplies directly in the community instead of from the downtown Health and Human Services office, where social distancing is difficult. That move let Buncombe serve triple its usual number of clients — up to 150 per week, from a pre-pandemic level of about 50. Although most syringe services have since returned to the HHS office on an appointment-only basis, Upham says, the county updated its formal safety and security plan to ensure some community distribution can continue.

The nonprofit Steady Collective also pivoted to mobile distribution when COVID-19 hit, says Hillary Brown, to ensure social distancing. The harm reduction group’s co-director (who uses they/them pronouns) notes that the shift wasn’t easy. “Steady is a very hands-on operation; we spend a good bit of time with participants,” they say. “We have tried to handle that as gracefully as we can.”

But the pandemic has pushed Brown to expand Steady’s services as well. Beyond syringes and naloxone, the nonprofit is also handing out advice about how to avoid spreading the virus and distributing masks and hand sanitizer.

“It does feel like we’re a lot of folks’ only source of information about this illness, because a lot of the folks that we’re working with are homeless and don’t have access to the internet or any sort of media,” Brown says. And due to a lack of COVID-19 testing among unhoused residents, they add, “people haven’t taken it superseriously.”

Warning signs

While Steady hasn’t yet seen a dramatic increase in its number of people served, Brown says, volumes did rise noticeably in June. More worrying than overall numbers, they say, is who’s more often coming to get supplies: first-time clients and those who had made a previous commitment to quit opioids.

“Job loss, housing loss, just lack of access to money has really squeezed people,” Brown explains. “People who were sober are using again because of that stress.”

MAHEC’s Mahoney says people returning to drug use face additional dangers due to COVID-19. If they’re following social distancing guidelines to avoid the coronavirus, he points out, they’re more likely to be using drugs alone — which means no one is available to administer lifesaving naloxone in the event of an overdose.

And under what he calls the “umbrella of fentanyl,” Mahoney warns, overdoses are more likely now than ever before. The synthetic opioid, roughly 100 times stronger than morphine, is commonly mixed with heroin and other drugs to increase their potency, which makes judging safe doses more difficult. “I always tell people that they’re playing with a loaded gun, like playing Russian roulette with all the chambers filled, whenever they return to use,” he says.

Drugs cut with fentanyl were a problem before the pandemic, Upham notes, but COVID-19 has exacerbated the issue. Distributors and dealers are having trouble getting product, she says, and are under pressure to add fentanyl to make limited supplies go further.

“There’s issues in the supply chain for toilet paper — that’s also true for drugs,” she says. The county is distributing fentanyl test strips as part of its syringe services program and urging participants to test any drugs they plan to take.

Brace for impact

Mid-September will mark the critical six-month point since the start of local measures to control COVID-19, Upham says, and the county is preparing to weather the opioid-related behavioral health problems that may come. Over 60 patient slots for free suboxone treatment remain available through MAHEC and AMCHC, and the Dogwood Health Trust awarded Buncombe $382,000 in July to hire three community paramedics for overdose response.

MAHEC also recently received a $1.8 million, five-year federal grant to expand its Asheville-based addiction medicine fellowship program, which trains doctors to provide treatment services in rural communities. Dr. Nathan Mullins, the program’s director, hopes his work will boost the region’s future capacity to care for opioid users.

COVID-19 has shown that some of that treatment can be safely offered with fewer restrictions, Mullins says. Many patients, particularly postpartum mothers for whom in-person appointments are challenging to schedule, have used newly permitted telehealth visits to meet the requirements for medication-assisted treatment. And relaxed rules around the distribution of methadone and buprenorphine, two commonly used treatments, have let some patients take home larger supplies to keep up with treatment while quarantining.

Despite these positive developments, Mullins continues, access to and cost of treatment remain major issues during the pandemic, especially when insurance is tied to employment. “As people struggle to continue the treatment that for them so far has been successful, has kept them alive — it depends on when they get back to work,” he says. “And they don’t know how long it’s going to last. It’s month by month.”

Mullins emphasizes that, as government officials struggle to contain the COVID-19 crisis, they must not lose sight of the opioid epidemic. The urgent nature of the coronavirus, he argues, shouldn’t displace efforts to address the chronic problem of drug use.

“It’s not a pandemic, where we’re going to come up with a vaccine in a year or two and it’s going to go away,” Mullins says. “This is something we need consistent treatment and funding for.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.