Sometimes, it takes an anthropomorphic critter to humanize what’s going on down the road.

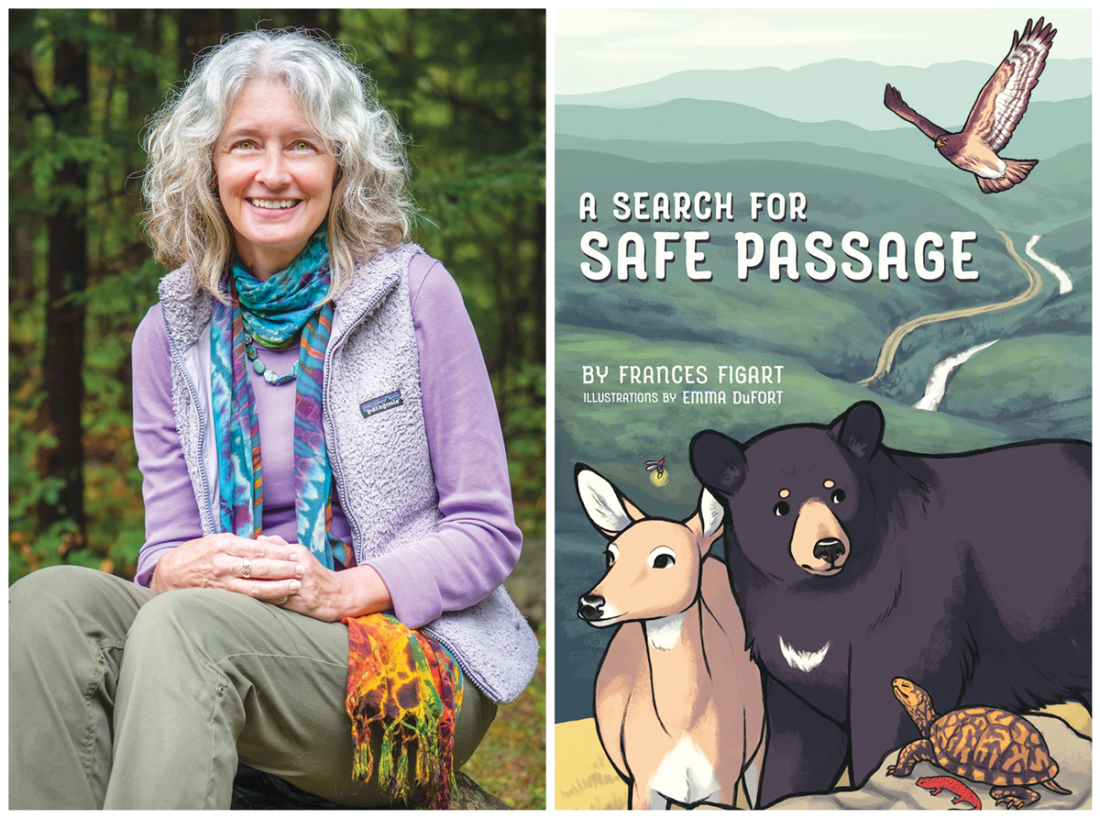

Look no further than Bear and Deer, two best friends living on Piney Knob, a made-up mountain near the North Carolina and Tennessee border. Both characters in A Search For Safe Passage, a new children’s book by eastern Tennessee-based author Frances Figart, are terrified of the “Human Highway,” where “huge, racing metal boxes with wheels” make it impossible for the animals to cross to the other side of the gorge.

In reality, the Human Highway is Interstate 40, and the journey Bear, Deer and their forest friends embark on is one that animals trying to cross face on a regular basis, Figart explains. And just as the fictional characters look for ways to safely bypass speeding cars and trucks, local conservation groups are pushing for animal-friendly pathways across the road.

“We can’t let roadkill just be this elephant in the room and not deal with it,” says Figart. “We hope this book will inspire other people to raise awareness in their own communities about the need to help animals travel safely to find food and mates and habitat.”

Price to pay

As a child growing up in eastern Kentucky, Figart remembers feeling upset when she saw animals killed on mountain roads. She tapped into those memories over the six weekends it took to write her debut children’s book, thinking the whole time about the kind of story she would have wanted to read as a kid with her own mother.

One distinct challenge was the subject matter, inherently dark for small children. While Figart wanted to accurately portray animal mortality, she made a conscious effort to keep the tale from becoming too gruesome. Most of the story’s characters have memories of a friend or family member who was killed by a car, but those deaths are not described in detail.

“We all know what it looks like to see a dead animal on the road,” Figart says. “I tried to leave it more nebulous and less graphic.”

But Figart’s effort to save animal lives goes beyond the pages of her book. In February, she and six conservation groups launched Safe Passage: The I-40 Pigeon River Gorge Crossing Project, a collaborative effort to collect data, fundraise and implement wildlife crossings along a 28-mile stretch of interstate linking Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee.

Over the last 16 years, traffic volume along this stretch of highway has increased by 43%, the coalition reports. More than 26,000 vehicles pass through the corridor each day — as do many bears, white-tailed deer, elk, bobcats, coyotes and a host of smaller species traveling between the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and surrounding public lands.

From 2017-2019, the N.C. Department of Transportation responded to 3,437 wildlife-vehicle collisions in the 18 westernmost counties of North Carolina. Those collisions resulted in more than $10.5 million in property damage and at least 189 human injuries.

Wildlife casualties are likely much higher, says Liz Hillard, a researcher with Wildlands Network. From September 2018 to December 2020, her team recorded 140 elk, white-tailed deer and black bear mortalities along the I-40 stretch. “That’s just a fraction of what’s going on out there,” she says.

No one wants to see dead animals littering the side of the road, says Figart, who also serves as the Safe Passage coalition’s outreach chair. But in some ways, it’s more dangerous ecologically when animals don’t attempt to venture across the interstate. If wildlife becomes stuck in a small portion of available habitat and can’t venture to find mates, a phenomenon known as the barrier effect, species are forced to continually mate with genetically similar relatives. That lack of movement reduces genetic diversity and can lead to less healthy populations.

In Figart’s book, this is modeled through “Turtle’s Law,” a rule imposed by the forest’s leaders banning the animals from crossing the highway. But Bear doesn’t have a mate, and he can only find a female companion by venturing across the gorge.

“It’s just one of the concepts we’re trying to get across through the characters,” Figart says. “When kids come out of the book, we hope they’ll have a better understanding and maybe a good discussion with their parents about it,” Figart says.

Passing through

Using 120 cameras mounted along the edge of the roadway, Hillard and her team are working to analyze how large mammals like bears and deer use existing structures like culverts and underpasses to safely cross the interstate.

In partnership with the National Park Service and the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, the team also outfitted 13 elk with GPS collars to track where the animals are traveling and how they approach highway crossings. By late summer, Hillard plans to map where animal mortality rates are highest along I-40 and determine areas where mitigation could be most successful.

Preliminary findings show the vast majority of animal casualties occur where I-40 cuts through public land. Of immediate interest is Exit 7 at Harmon Den, a popular driving route to access Max Patch and the site of a safe elk crossing reported in 2015, says Jeff Hunter, senior program manager at the Asheville field office of the National Parks Conservation Association.

NCDOT plans to redo this bridge in the fall and will include 9-foot tall fences to safety direct wildlife to paths under the bridge, says David Uchiyama, department spokesperson. The animal safety additions are included in the project’s $9.5 million price tag, he adds; Hunter and the Safe Passage coalition are concurrently working to fundraise for additional wildlife fencing outside the project’s limits.

NCDOT has identified four other bridges in the Safe Passage project zone that will need updates in the coming years. Hunter anticipates making formal wildlife crossing recommendations to state agencies after the research study is completed later this year. Methods on the table include more fencing, box culverts, open-span bridges and wildlife overpasses.

In Figart’s book, the animals ultimately find a “land bridge” allowing them to safely cross the Human Highway. That path is modeled after what the Safe Passage coalition dubs the “double tunnel,” a section of I-40 where the road cuts through the side of Snowbird Mountain in Haywood County. The natural landscape is preserved on top, allowing animals to avoid the interstate altogether. Many of the book’s illustrations by Emma DuFort are modeled after images taken by the roadside cameras, Figart adds.

Federal funding for wildlife crossings may soon be available, Hunter adds. The House of Representatives passed an infrastructure bill in July that earmarked $250 million to fund pilot programs to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. Although the Senate never voted on the proposal, Hunter is optimistic discussions will resume later this legislative cycle.

The next generation

Factor in climate change, Hunter says, and the need for safe wildlife passageways significantly heats up. He points to the Nature Conservancy’s Migrations in Motion data tracking map, which depicts a wave of mammals, birds and amphibians funneling through the southern Appalachian Mountains as they travel north to escape rising temperatures.

But more wildlife passing through the region, coupled with more cars on I-40 as tourists flock to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, could spell disaster without designated crossings in place.

“For me, this project plays a huge role in ensuring that our wildlife has the opportunity to move northward to ameliorate the climate change,” Hillard says. “It’s a really important part of this when we start thinking long-term about the pride we have in our biological diversity and conserving the wildlife we have here.”

But it will likely take decades for the necessary infrastructure changes to be built, Figart notes. She hopes her book, intended for children ages 7-13, helps spark family conversations around road ecology before it’s too late.

“The future builders of these things are 7, 8, 9 years old right now,” Figart says. “We want kids to really get involved when they’re young so they will continue to be passionate as they grow up.”

A Search for Safe Passage is available for purchase through the Great Smoky Mountains Association at avl.mx/92r.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.