It’s well known that fentanyl, a cheaply made opioid, is in the local drug supply. Fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin, and counterfeit versions of it are added to other substances as inexpensive fillers. Its potency can be deadly for those who haven’t developed a tolerance.

Fentanyl isn’t the only adulterant found in street drugs, however. And fentanyl or xylazine test strips — two methods of drug checking available from local nonprofits and Buncombe County Health & Human Services — only test for the presence of those two substances.

That means people who use drugs don’t always know what they are taking or how much. For example, a drug sample collected in Asheville in January contained eight substances, says Justin Shytle, harm reduction coordinator for Sunrise Community for Recovery and Wellness. (Shytle uses “they/them” pronouns.)

That sample contained fentanyl and a chemical used to make fentanyl called 4-ANPP, which Shytle says are both common in Western North Carolina. It also contained six other contaminants: two other chemicals similar to 4-ANPP; caffeine; cocaine; xylazine, also known as “tranq”; and procaine, a dental anesthetic. “This amount of stuff is pretty wild,” they admit.

Shytle is armed with this information because last year, Sunrise began participating in a nationwide drug-checking program. The nonprofit collects substances or drug paraphernalia samples from people who use drugs and want them checked, then anonymously mails them to a UNC Chapel Hill laboratory. These submissions are analyzed using a powerful gas chromatography mass spectrometer, or GCMS. An analysis is posted online, also anonymously, so that people who use drugs can find out the chemical compositions of what is circulating in their community and make informed choices.

“I didn’t know how a lot of folks would take to it,” says Shytle of the drug checking. “But we actually have had a huge response from our peers [Sunrise uses this term to refer to its clients]. They’re like, ‘Please test this, I don’t know what this is!’”

“A lot of people don’t think their stuff’s going to have anything in it,” says Sunrise harm reduction specialist Pazi Harbin. “But now we’re seeing — yeah, everything’s cut.”

Sunrise has sent about 25 samples to UNC’s lab in the past four months.

‘Drugs have gotten more dangerous’

Drug checking is “a harm reduction practice in which people check to see if drugs contain certain substances,” according to the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse. The goal is to give people who use drugs more information about what they’re putting in their bodies, reduce risks and potentially save lives.

Research shows “people knowing what’s in their drugs can make them safer,” explains Dr. Shuchin Shukla, an addiction medicine physician based in Asheville. For example, a study published in Harm Reduction Journal in 2019 showed that some people who tested their drugs with fentanyl test strips and got a positive result changed their drug use behavior. They discarded their drug supply, kept naloxone — the opioid-reversal drug — nearby or used the drug in the company of someone else for safety.

“The reason people overdose is not because they use drugs,” Shukla explains. He points out that many people take drugs — for example, being administered pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl as a painkiller during a surgery — and don’t overdose because the licit drug supply is unadulterated and measured. People overdose, Shukla continues, when the amount of drugs is too large, too potent or too contaminated with something else. He notes that substances have gotten “a lot more dangerous … much more potent, much less predictable.”

Fentanyl has been identified in the local drug supply since 2015, according to Buncombe County’s Opioid Settlement Strategic Planning Report, which was published in May. That year, 33% of overdoses among county residents involved fentanyl, according to the report. By 2021, that percentage had risen to 74%.

Polysubstance deaths — when multiple drugs contribute to an overdose — have also increased. In 2015, 10% of all overdose deaths among Buncombe County residents involved a stimulant, such as methamphetamines, combined with another drug, according to the county’s report. In 2021, deaths involving a stimulant and another drug comprised 50% of such deaths.

Evidence-based treatment, including medication-assisted treatment, for substance use disorders can reduce deaths from overdose. And referrals to treatment can be made by organizations that facilitate drug checking, like Sunrise.

“Drug checking helps people who use drugs to engage with harm-reduction providers for other health promotion services like HIV testing, wound care and referrals for addiction treatment,” Shukla says.

How it works

There are several drug-checking labs and programs nationwide. Sunrise uses The UNC Street Drug Analysis Lab, as well as a web-based service called StreetCheck.

In the past two years UNC’s lab, which is housed in the department of chemistry, has mailed out nearly 7,000 sample collection kits and analyzed 5,000 samples, says the lab’s social/clinical research specialist Colin Miller.

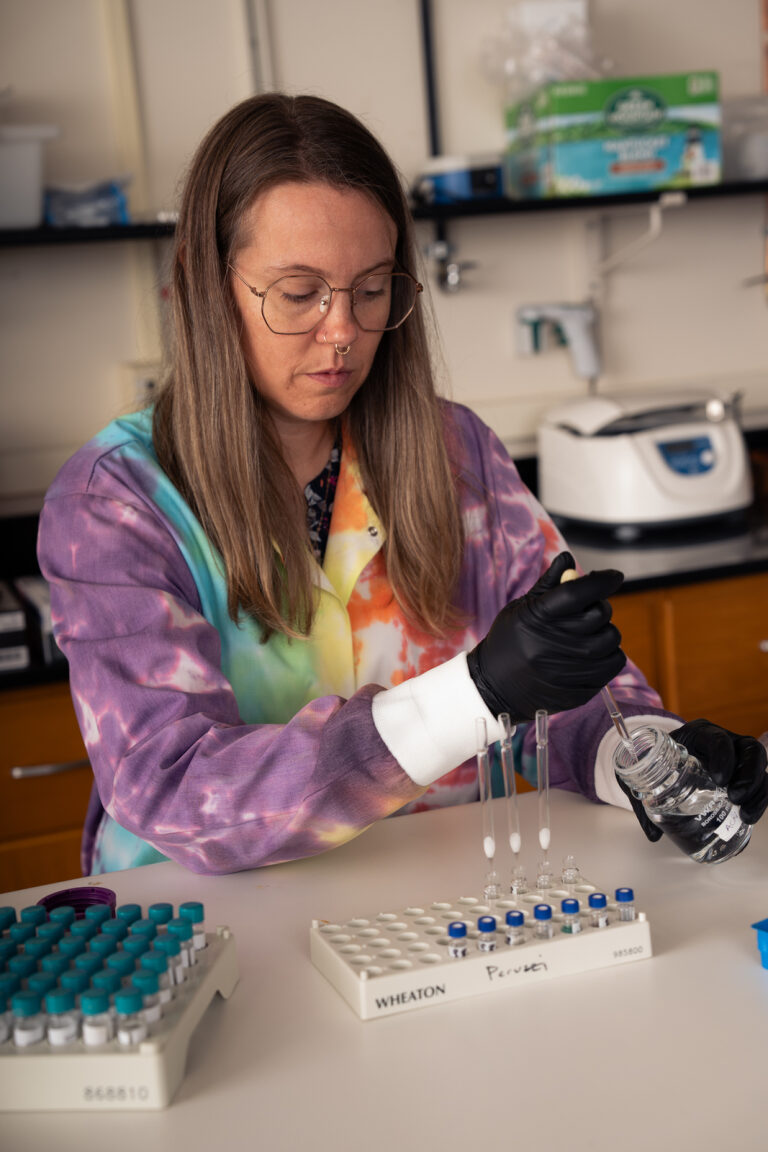

The lab supplies Sunrise with a sample collection vial and 2 milliliters of methyl cyanide, which renders the substance unusable as a drug and makes it legal to mail, according to the lab’s website.

People who use drugs get the sample collection kits from Sunrise and then gather trace amounts of the drug they want checked. Sunrise then mails the samples in a prepaid package to UNC’s lab. The sample collection kit also contains a card whereby the person who submitted it can share more details: describe the appearance of the drug, share whether it was involved in an overdose, describe how using the drug feels.

The lab uses a GCMS — a spectrometer with infrared lighting — to identify the chemicals and their potency. The lab has federal Drug Enforcement Administration authorization to handle Schedule 4 controlled substances. Although testing with a GCMS takes around 10 minutes, the process of mailing the samples to Chapel Hill and posting the results online so far has taken two to three weeks.

While all data is anonymously collected, detailed lab results of the substances identified in each sample are published online with numerical identification. People who donated the sample also have the number, so they can look up the results online without having to communicate with the organization that mailed it, explains Miller. People who use drugs can also access the online results via a QR code; Shytle says they will print out the results and the QR Code for the person who donated the sample.

Miller explains that Sunrise is able to check drugs through UNC Street Drug Analysis Lab at no cost, as part of an Opioid Abatement and Recovery Research Project within the N.C. Collaboratory at UNC Chapel Hill, a research facility providing information for policy development. UNC’s lab director, Dr. Nabarun Dasgupta, is one of five recipients of $380,000 in funding for such projects. Other harm reduction and public health organizations pay $20 per sample for the lab’s services.

StreetCheck, the other drug-checking service used by Sunrise, is also free. Created by the Massachusetts Drug Supply Data Stream, the online portal and app integrate drug-checking data from labs nationwide. The samples come from both law enforcement drug seizures and community-collected samples. Shytle says the service uploads the drug-checking data received from UNC’s lab results onto StreetCheck to make the information more widely accessible.

Like UNC’s lab, StreetCheck posts data online anonymously for anyone to see. Advocates for drug checking underscore the importance of anonymity. “People are afraid of being identified [as drug users],” explains Miller. “That may sound paranoid, but people who use drugs, who are dependent on drugs, are essentially walking felonies.”

The UNC Street Drug Analysis Lab partners with 150 organizations, like methadone clinics or syringe exchange programs, across 35 states. Miller says the lab makes it clear to every program it doesn’t want them “recording any of the person’s data — anonymity is a very important part of this.”

‘A needed thing’

The eight substances found in the street drug donated by Sunrise were an unusually high number, Shytle says. The nonprofit’s samples sent so far have primarily tested positive for fentanyl and 4-ANPP.

Nevertheless, people who use drugs have experienced “shock” at the array of substances that come up in UNC’s lab analyses, Shytle says. For example, recent drug testing showed bromazolam, a synthetic benzodiazepine similar to Xanax that hails from the United Kingdom, in the local drug supply.

“It’s showing drug checking is a needed thing,” Shytle says.

The UNC Street Drug Analysis Lab’s two- to three-week turnaround means it can only indicate larger trends. For example, Miller says that a drug-checking program in Greensboro first identified xylazine — a veterinary tranquilizer not approved for use in humans — in the North Carolina drug supply.

Some people may wonder how useful that information is after the fact, when the substance that was checked may already have been used. Advocates for drug checking say people who use drugs can make better-informed choices in the future and reduce the risk of death. “Knowing after the fact [what’s in drugs] is incredibly important,” Miller says. “The drug trade is very regional. It’s important for people in the area to understand what the lay of the land is.” Recently a number of samples from WNC have shown the presence of nitazene, a synthetic opioid as potent as fentanyl. “It’s very good for drug users who are in that region [to know] we’ve found the compounds,” he says.

There is a quicker way to analyze a drug’s purity and potency. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, or FTIR, analyzes the absorption of light on various substances in minutes. FTIR analysis is considered highly sensitive and accurate; the service has been used at music festivals in Canada and Australia, among other places.

However, an FTIR spectrometer costs $10,000 to $15,000. Shytle says they are currently researching funding sources in the community.

“Once we have rapid testing, it’ll help a lot with OD rates, because people can better prepare,” explains Harbin from Sunrise. “We’ll be able to see if there’s going to be a bad batch of stuff going out and let people know ahead of time.”

So now, one way or another, tax payers are providing free tests for dopers. How bizarre.

“The goal is to give people who use drugs more information about what they’re putting in their bodies, reduce risks and potentially save lives.”

But the ultimate goal should be to get people off drugs. Perhaps some tough love, coupled with housing incentives and expectations of accountability. Our culture needs to move away from perpetual enabling and victimology.