It was a full house at the Kenilworth Presbyterian Church for the neighborhood’s annual celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day on Monday, Jan. 19. Listeners filled the tables, sat on the floor and stood along the walls all the way to the door.

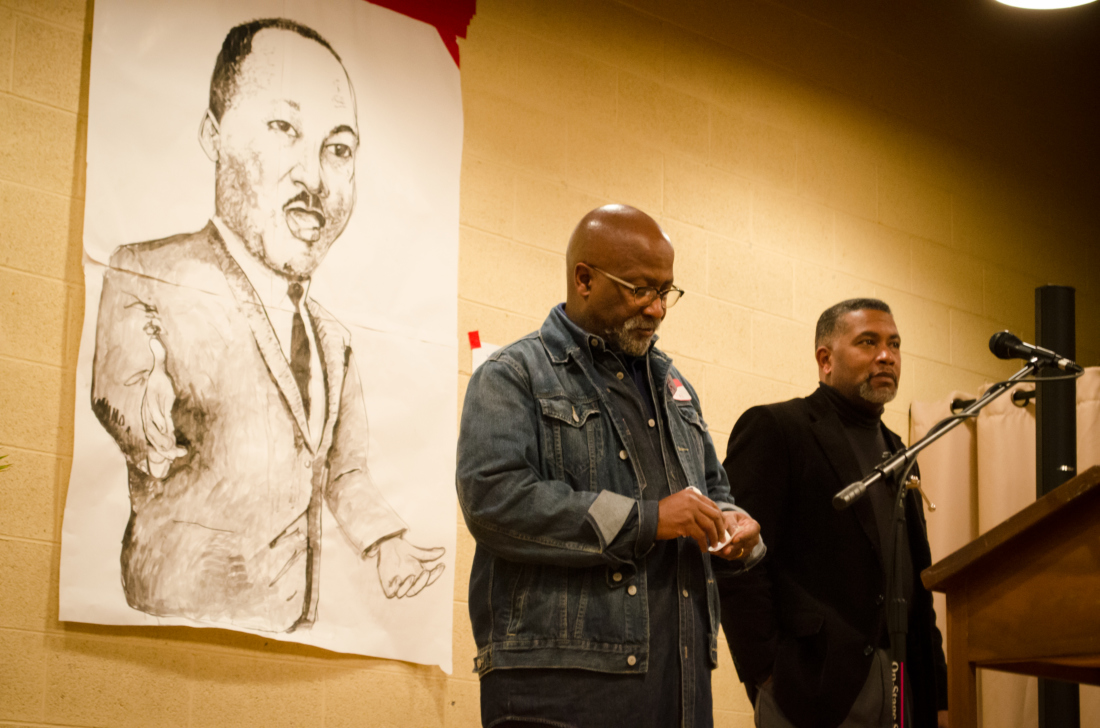

The event centered around a discussion of the “History of Civil Rights in WNC and the Current State of Racism Affecting Black Asheville,” and featured speeches by Darin Waters, assistant professor of history at UNC Asheville, and Dwight Mullen, professor of political science also at UNCA. Marvin Chambers, a founding member of the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality and a leader in North Carolina’s civil rights movement, served as moderator for the discussion.

In his opening remarks, Chambers lamented the lack of a sustained interest by the general public in the issues affecting black Americans, noting that “there’s Martin Luther King Day and then there’s Black History month and then there’s nothing.”

“I’m saying to you as we proceed through the night, don’t let what happens here tonight stop here tonight, let it continue,” Chambers said. “Begin to learn and understand those people with whom you come into contact. You don’t have to love everybody, but you have to at least understand them.”

In his address, Waters sought to provide an historic context for listeners, noting that the study of African American history and identity in Appalachia, and especially in Asheville, is a fairly recent academic field. He noted his own academic advisors initially discouraged him from pursuing a dissertation in African American history in Buncombe County, as there was uncertainty as to how much information was even available.

“Most historians find it more rewarding or beneficial to study areas of the South where the African American population was much larger,” Waters noted. “But when you have lower numbers, the dynamics are much different….the population is small, so the ability to be able to challenge racial marginalization is much more difficult.”

Waters provided the audience with other insights as well, including the continued economic disparity between black and white Americans, the lack of perceived racial progress in the country and the absence of African Americans from the “collective memory.”

“Every time I’m in Raleigh and I drive by Union Square and I see no monument to anyone who looks like me, I say that when it comes to our collective memory there is a problem,” he said. Waters added that Asheville continues the national trend of a low number of monuments to African American history in public spaces.

Mullen’s talk began with his own personal experience of coming to understand the civil rights movement. “I was not a King advocate,” he said, noting that his younger self agreed more with the position of the Black Panther Party.

However, Mullen said his perspective on King was changed by his experiences in college and his interactions with civil rights leaders Ralph Abernathy, Julian Bond and John Hope Franklin.

“This is what I came to: All three of them, they talked to me in the terms of warfare,” Mullen said. “They talked to me as though they had been in the battle, they had fought in the street, bled and died to win this war. And they were proud of it.”

“I remember Ralph Abernathy, discussing with me, holding Martin Luther King as he died,” he added.

Mullen noted that the civil rights movement is different in the country today, though inequality still remains. “You don’t have to worry about fighting the war,” he said, paraphrasing Abernathy, Bond and Franklin. “Laws have changed, these things are over. But the issue is, will you win the peace?”

Asking the audience, “Did we win the peace here in Asheville?”, Mullen discussed parallels in the African American experience between the end of the Civil War, the end of the civil rights era and recent events. “Those parallels get eerie,” he said, pointing to high rates of poverty, low economic development and violence against black men.

“The end of the Civil War, the Reconstruction era was marked with violence…you’re talking about chain gangs, incarceration, lynching,” Mullen said. “And you say where’s the parallel with that? Excuse me. Excuse me! Let us talk about incarceration being higher than it ever was in this country’s history, let us talk about rates of poverty as forms of violence…You start putting it together and you say, ‘The police are killing more African American men and women than were lynched at the height of the lynching era.’”

Mullen concluded by noting that, “We lost the peace because of administration” and failures in public policy. He encouraged the audience to develop person-to-person level connections with neighbors, advocate for people of color and other marginalized communities and hold themselves and others accountable.

“It’s not just your accountability, it’s the accountability of elected officials, appointed officials and folks across the racial divide,” Mullen said. “Suddenly, if you see something, that’s your neighbor and that makes it your business too.”

The Kenilworth Celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. also included a performance by UAI Boyz from the Urban Arts Institute.

As one who attended, I can attest to this being a very well written, complete article. Thank you!