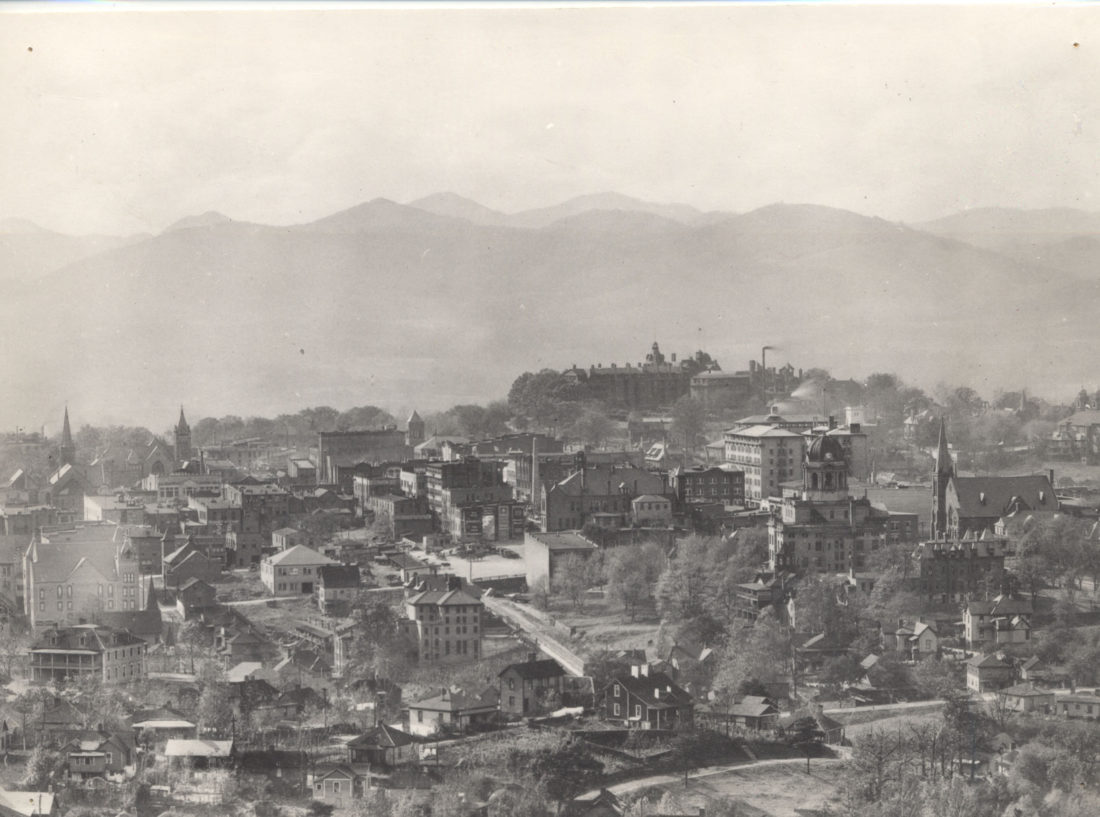

On Jan. 1, 1920, at the dawn of a new decade, The Asheville Citizen reflected on the previous year and what it indicated for the city’s imminent future. After several years of financial distress and uncertainty on account of the Great War, 1919 marked the start of a 10-year boom period for the city, as well as much of the nation. The following excerpts and storylines, unless otherwise noted, come from the paper’s Jan. 1, 1920, edition.

“The year has in many respects been an unprecedented one for Asheville,” the paper wrote, “but a retrospect of the building activity during 1919 immediately causes one to pronounce the last twelve months as the ‘building year’ for the city.” Permits, the paper continued, were “within a few hundred dollars of one million” (or roughly $20 million in today’s dollar).

Along with commercial buildings, the city saw plenty of new homes go up. “The suburb sections are fast becoming attractive to the home builder and many bungalows are being erected in all sections of the city,” the paper proclaimed. “One reason advanced for this is the fact that the trolley systems extend to all the more densely populated suburban districts, and a schedule to accommodate the residents of these sections is maintained.”

According to The Asheville Citizen, the federal census listed the city population at 18,000 in 1910; by 1919, based on estimates from the city directory, the population climbed to 45,000. Post office deposits, the paper continued, increased from $50,000 in 1905 to over $160,000 in 1919; meanwhile, bank deposits soared from $1 million in 1900 to around $10 million in 1919.

“On every side in Western North Carolina can be seen the greatest activity, the spirit of progress is written large on the face of every man and big things are not only dreamed of, but are being accomplished,” the paper promulgated.

Similar declarations were made by W.B. Davis (whom The Asheville Citizen described as “one of the best-known bankers in North Carolina”). In his talk with the paper, Davis gave readers plenty to be excited about.

“Public improvements indicated a strong spirit of progress [in 1919],” the banker announced. “New schools seem to have been in universal demand. … Roads and more roads; good roads and better roads — this is the purpose that found expression in every mountain county.”

Davis also addressed Asheville’s growing appeal to visitors. “The tourist season just past was fairly overwhelming in volume, taxing all facilities of transportation and house to capacity,” he said. “Each year witnesses a larger pilgrimage to the beautiful mountains of the Land of the Sky. More visitors come from distant states and foreign countries. Many stay longer than was formerly their custom.”

In his summation, Davis asserted, “Western North Carolina is confident, optimistic in the highest degree, and eager to be busy with the tasks that will come to our hands in 1920.”

Davis’ words proved prophetic. As Nan Chase notes in her 2007 book, Asheville: A History, the city saw 65 commercial and public buildings go up throughout the 1920s.

Of course, the boom didn’t last forever. Rather, it came to a disastrous end on Oct. 24, 1929, when the stock market crashed. Soon thereafter, several of the region’s largest banks closed, as the Great Depression continued to ravage the entire country. Locally, the city of Asheville did not pay off its pre-Depression debts until July 1, 1976.

In Thomas Wolfe’s novel, You Can’t Go Home Again, published posthumously in 1940, the writer censures the shortsightedness of Libya Hill, his fictionalized version of Asheville. In the book, Wolfe writes:

“They had squandered fabulous sums in meaningless streets and bridges. They had torn down ancient buildings and erected new ones large enough to take care of a city of half a million people. They had leveled hills and bored through mountains, making magnificent tunnels paved with double roadways and glittering with shining tiles — tunnels which leaped out on the other side into Arcadian wilderness. They had flung away the earnings of a lifetime, and mortgaged those of a generation to come. They had ruined their city, and in doing so had ruined themselves, their children, and their children’s children.”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.