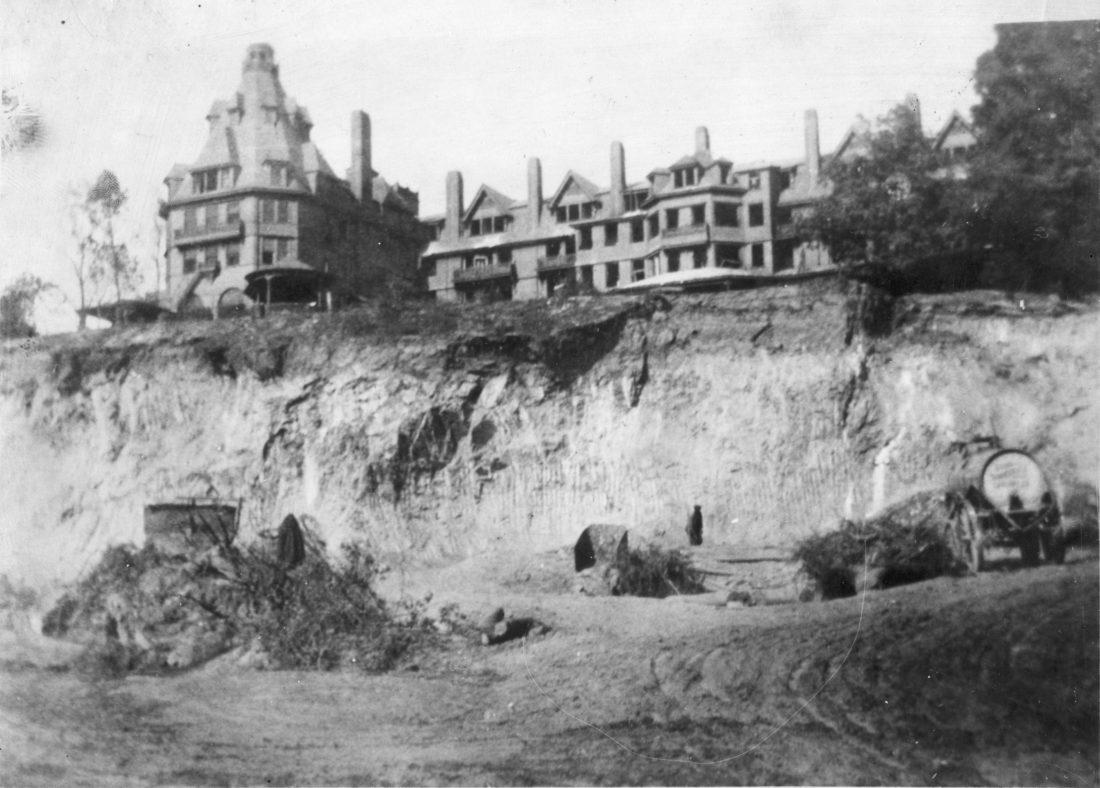

Debate about development is nothing new in Asheville. One of the more heated examples took place in the final months of 1922, when local developer E.W. Grove announced plans to raze the original Battery Park Hotel in order to replace it with a modern, 200-room, fireproof structure (see, “Asheville Archives: ‘On the Highest Hill in the Town,’” Oct. 3, 2017, Xpress). In addition to tearing down the 1886 hostelry, the project called for the demolition of the property’s hill, which amounted to roughly a quarter of a million cubic yards of dirt.

On Nov. 28, 1922, The Asheville Citizen reported, “While Mr. Grove appreciates the sentiment that has existed for many years on the part of patrons of the Battery Park Hotel and the residents of Asheville toward Battery Park Hill, the hotel is rapidly outgrowing its period of usefulness.”

Still, not all Ashevilleans were on board with Grove’s big plans. On Dec. 13, one resident wrote to the paper, calling the project “the greatest piece of vandalism that was ever attempted in this whole section.” The writer (who signed off as “The Kicker”) continued:

“It would, of course, be all right to remove the old hotel and erect a new one in its place, but to cut the hill down and make it on a level with Patton Avenue and Haywood Street, would destroy its beauty and, in my judgement, cause deep regret and sorrow to the many thousands of people who have spent many happy days upon the porches of Battery Park Hotel watching the mountains in all of their beauty. Asheville, without Battery Park Hill, and Battery Park Hotel, would be like the play Hamlet, without Hamlet.”

Two days later, the newspaper published yet another letter (this time written by “A friend of the hills and mountains”). In it, the writer posed several questions about the project and its future implications. Namely, if Battery Park Hill came down, what would prevent additional mounds and mountains from falling?

The letter ended with a cautionary note:

“Since everything is being put on a commercial basis, we natives of this Land of the Sky, which we thought was ours, had better look with fear and trembling on our beautiful blue sky, for some one will come along some day bent on what he will call progress, (but not, Mr. Editor, of the soul or heart or mind, but just business progress), and will want to extract all the color from our sky and glorious sunsets, to make paint or blueing, or anything that makes money. And what can we do then, any more than now?”

Opposition to the project, however, was not universal. In one published response, resident Charles Lee Sykes dismissed the previous letter writers as “sentimentalists.” On a similar note, Grove’s business associate, A.H. Malone, derided the complaints, accusing the authors of hyperbole. Asheville had many hills and mountains, he wrote, arguing if the city was “situated on a prairie with only one lone elevation, which you would infer from the letters of some of the critics, then it would be a most cruel thing, indeed, to cut down this hill.”

Other residents, like Judge Frank Carter, expressed ambivalence about the project. While he bemoaned the loss of the hostelry and its hill, he claimed that opposition to Grove’s plans was futile. If the city wanted to preserve the location and site, he wrote in the Dec. 16 edition of The Asheville Citizen, cooperation between the building’s former owners and civic leaders should have been established long ago. “But the vision was lacking and the Hill perishes,” he opined.

Carter went on to note:

“Hills are the handiwork of the Most High, which man rarely touches but to mar. This hill of hills had a beauty which was able to withstand much of violence, but it couldn’t stand everything. It was tortured by many cruel gashes and shamed by the multiplication of architectural excrescences; and still it was the throne of our civic pride. But when its fairest face was slashed and scarred for a thousand feet or so of business frontage on Government Street and Patton Avenue, and its then only remaining natural slope, its proud front toward Pisgah and The Rat, was murdered by the monstrosity of Otis Street, the Hill of symmetrical beauty and tender memories was pretty well done for.”

But unlike some of the paper’s previous letter writers, Carter saw reason for hope in Grove’s plans. At the end of his article, the judge declared: “Towns, no less than religions, are builded on faith; and when you tell the world that large-minded investors have the faith in Asheville that literally removes mountains, the world will not return unto you void.”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

Amazing when you consider that the hill the old Hotel stood on was taller than the new Hotel….and that present-day Coxe Avenue was once a ravine that was filled with Battery Park Hill…. The Asheville cityscape is much altered from the one I knew in the late 60’s and early 70’s – but how vastly different from the 1900’s-10’s!!

The top of Battery Hill was level with the 7th floor of the new hotel.

Here is a link to the UNCA map collection – some of these Sanborn Insurance maps are a little tedious to look at, but you can see at least the street layout and setup of businesses, etc downtown prior to the 1920’s

https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/ncmaps/id/4263/rec/8

Here is a detailed section of a 1917 map showing the Battery Park Hotel & adjacent streets, etc..

https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/ncmaps/id/4263/rec/8