In his 2002 essay “Black Professional Baseball in North Carolina from World War I to the Depression,” writer Bijan C. Bayne offers a detailed look at black-owned ballclubs in the state, with a specific focus on the Asheville Royal Giants.

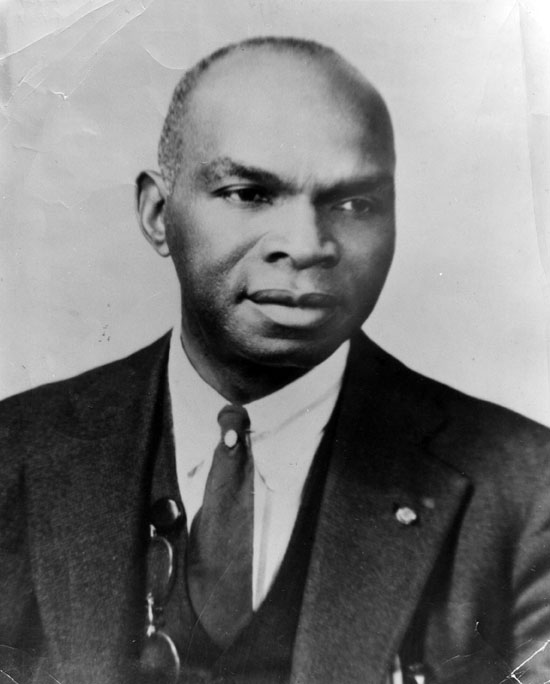

According to Bayne, the Royal Giants were established in 1916 by Edward W. Pearson, a local businessman and developer of West Asheville’s Burton Street community. The team name, the writer notes, “was not uncommon for ‘colored’ teams in the South at the time — two pre-1920 Memphis teams and a Louisville team also bore the name.”

In addition to playing ball, Pearson’s players held regular jobs. The essay states that many of the teammates worked in the hospitality industry with positions at the Grove Park Inn, as well as the Battery Park and Vanderbilt hotels. Others were employed by local railroad companies, while some worked directly for the Vanderbilt family.

Though there was little coverage of the team, Bayne writes, “they were without a doubt one of the best professional outfits in North Carolina.”

What available coverage does exist dates from 1919-27, with the majority of local articles written between 1919 and 1922. Much of the reporting is limited to brief game summaries. However, there are two articles that spotlight in detail the team’s talent.

The first, published by The Asheville Citizen on Aug. 27, 1919, not only highlights the club’s athleticism but also confronts many of the prevalent stereotypes of the day. And though at times the paper serves to perpetuate other misconceptions, particularly as it relates to claims of purely positive race relations in Asheville, the piece as a whole actively works to challenge and dispel the more racist depictions of African-Americans held by many citizens during the Jim Crow era.

The Aug. 27, article begins by noting:

“Asheville fans of both races who have been enjoying the games played here between the local team of negroes and dark-skinned diamond stars of other cities are promising a considerably extended season, present prospects indicating that the colored players will still be unraveling their schedule when the world’s series is settled.”

Yet, as the paper makes clear, not all white residents were on board in supporting the Asheville Royal Giants. Many, the paper suggested, held exaggerated views of the team’s athletic abilities. The article directly attributed this to the influence of such popular performers as Al Field, known for his blackface minstrels. “The fan who goes to Oates park in the expectation of seeing a bare-handed colored giant catching and a first-baseman stopping ’em with a short stop’s discarded glove has another thing coming,” The Asheville Citizen asserted.

A little over a year later, on Oct. 3, 1920, The Sunday Citizen highlighted the team’s continued success. According to the paper, the club had played a total of 94 games during its previous season, with a record of 71 wins, 18 losses and five ties.

The article goes on to report the Royal Giants upcoming series of expo games against the Greenville Stars, another all-black team noted for its stellar (albeit less demanding) record of 21 wins and four losses. The series was part of the annual Buncombe County Colored Agricultural Fair, which like the Royal Giants, was also founded by Pearson.

“It is stated that in the two teams will be some of the best colored baseball talent to be found in the south,” the article concluded, “and it is safe to say that either of the games will be far from amateurish.”

Bayne echoes this final sentiment near the end of his 2002 essay, writing: “Though they were unsung on the national scene and remain but a footnote in most black baseball literature, black North Carolina teams played the best segregated competition available[.]”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents; antiquated and offensive word choice included in these excerpts reflect the language of the time period.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.