This week’s column is an accompaniment to the article spotlighting local initiatives commemorating the 400-year anniversary of the landing of the first enslaved Africans in English colonies in America in 1619 (see “Asheville reflects on the legacy of slavery,” Oct. 16, Xpress). Several local historians and educators who spoke with Xpress about the anniversary noted a common misconception about slavery in Western North Carolina: namely, that many people still believe slavery did not exist in the region.

In 2009, local historian Terrell T. Garren compiled the report Slavery, Civil War and Freedom: A Period Study of African Americans from Buncombe County, Henderson County and Madison County, North Carolina for The Center for Diversity Education at UNC Asheville. The study includes 1860 census records for the three counties. According to these records, Buncombe County had 1,907 slaves and 283 slave owners, Henderson County had 1,371 slaves and 207 slave owners, and Madison County had 213 slaves and 46 slave owners.

Among Buncombe’s 283 slave owners, 54 owned 10 or more enslaved people. Nicholas Washington Woodfin topped the county’s list at 122.

In Henderson County, which at that time included today’s Transylvania County, 38 slave owners owned 10 or more enslaved people. Daniel Blake topped the county’s list at 59.

Finally, in Madison County, five slave owners owned 10 or more slaves. J.A. Gudger topped the county’s list at 22.

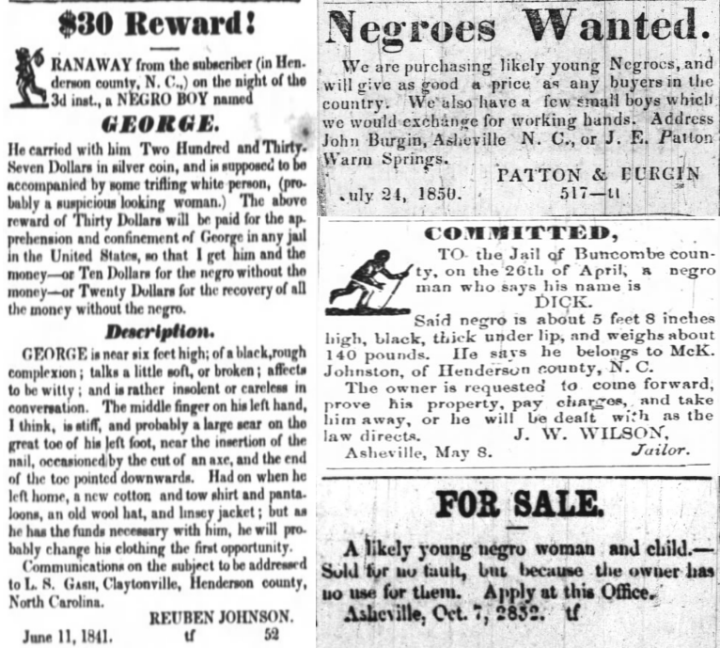

Along with the available census reports, local newspapers offer a glimpse into the region’s familiarity with slavery. Below are a series of examples from local papers between 1841 and 1856.

Kimberly Floyd, site director at the Vance Birthplace, says she often encounters pushback from visitors who are uncomfortable with the tour’s discussion of slavery; others, she adds, are upset by her staff’s classification of the site as a plantation.

Academics, Floyd notes, typically define plantations as having at least 20 enslaved people, a minimum of 1,000 acres and a cash crop. The Vance family, she reports, had 18 enslaved people, 898 acres and over 2,000 pounds of bacon when David Vance Jr. died in 1844. Pigs, says Floyd, functioned at the plantation’s cash crop.

Today’s emphasis at the Vance Birthplace is on the stories of the enslaved. After leading visitors through the property and going over the types of jobs individuals held, guides conclude each tour with a request.

“We ask people — as they go through their day and their week and their month and their year — to consider thinking about the history that happened here and the work that was done here and the lives that were spent here and how they impacted what would happen,” Floyd says. “And we ask them to think about Zebulon Vance and his policies and how those affect us even today.

“And then we open it up for questions,” Floyd continues. “People typically stare at us in silence.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.