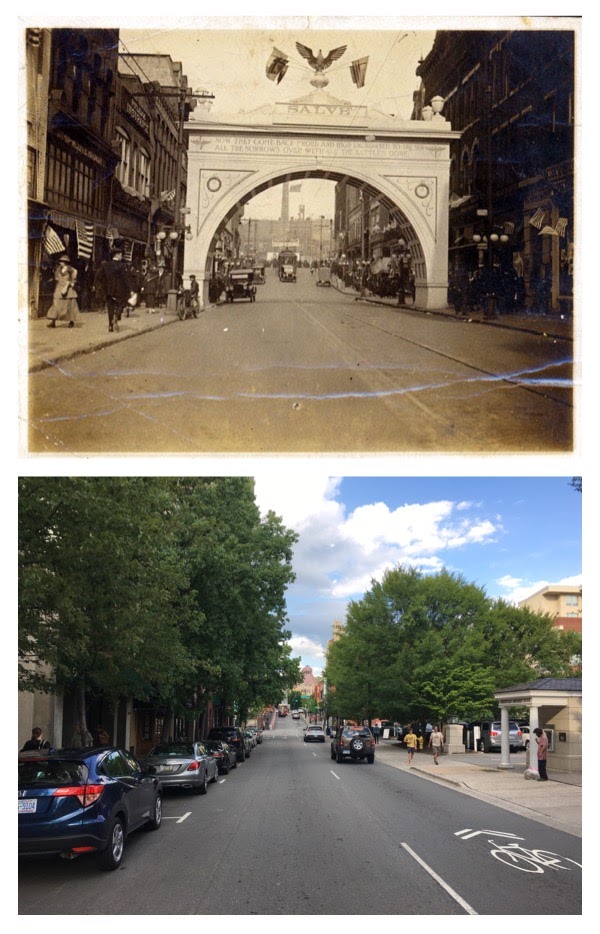

The Great War ended on Nov. 11, 1918. The following year, as U.S. soldiers returned home, cities and town across the country held celebrations. Asheville’s own revelry was led by a welcome committee that saw to the construction of a victory arch. Controversy over the arch’s inscription, however, would soon overshadow the plans for patriotic festivities.

On March 25, 1919, The Asheville Citizen included the following announcement from the city’s decorating committee, a subcommittee of the welcome committee:

“We propose to decorate Asheville from one end to the other. We would be a disgrace if we didn’t. We are asking the whole city to join in and help us. New York has built a glorious victory arch — but Asheville’s [arch] … compares mighty favorably with it — considering the size of the two cities. Also, don’t forget that the whole of it, almost, was donated by our carpenters, our painters, our lumber dealers, electricians, and others, because their hearts were in a glorious welcome home to these dear sons of Buncombe county.”

The victory arch, located on Patton Avenue between Church Street and Lexington Avenue, was designed by architect Charles Parker. In a March 9, 1919, article in The Sunday Citizen, the newspaper praised the design, paying particular attention to its centerpiece:

“The figure of the American eagle with outstretched wings now surmounts the apex of the structure, making an imposing impression as viewed from the west. … The body was moulded of plaster of paris by E. Stavenow, and the wooden wings were fashioned by the Asheville Supply and Foundry company, the work in both cases being highly artistic. The eagle stands five and a half feet high, and measures eight feet from tip to tip.”

The victory arch’s inscription read:

SALVE,

NOW THEY COME BACK PROUD AND HIGH UNCROWNED TO THE SUN

ALL THE SORROWS OVER WITH ALL THE BATTLES DONE

The controversy over the inscription centered on the use of the Latin word “Salve.” Many argued about its pronunciation — namely “Salvee,” versus “Salvay.” Others, including J.C. Pritchard, took issue with the word itself. On March 30, 1919, The Sunday Citizen reported:

“It was announced that the Latin word ‘Salve’ furnished by the architect with the design for the victory arch be replaced by ‘Welcome’ or some English equivalent, and that a new and simpler text be substituted for the present inscription on the west front of the arch. It was stated that the committee felt that while the Latin word had a sonorous sound and was associated with arches, an English word was more appropriate, and that a simple inscription should greet the soldiers instead of the highly martial one which now appears.”

On March 2, 1919, the controversy would lead to the resignation of several members of the welcome committee. On March 6, 1919, The Sunday Citizen featured a letter to the editor, poking fun at the fiasco surrounding the victory arch:

“The word Salve on the victory arch has puzzled a number of people. Many suggestions have been made as to its pronunciation and meaning. Now it is the rumor that the word is to be painted over. May I, as an humble citizen, urge that it be allowed to stay?

“In view of the recent eruption of the welcome committee, and the sore conditions that were brought about, it would be most appropriate to leave ‘Salve,’ painting out the accent mark, on the arch and give to it the good old every day, common-place, Anglo-Saxon pronunciation and meaning. This pronunciation is Sav, and the meaning according to Webster is an ointment to be applied to sores something to sooth; to gloss over. It would then stand for the willingness of both the welcome committee and the citizens of Asheville to sooth all eruptions and cure all sores and make conditions healthy for the sake of the returning boys who fought so hard across the seas for all of us.”

Ultimately, “Salve,” would be replaced by “Welcome.” The entirety of the westbound inscription would also be replaced. According to Mitzi Schaden Tessier‘s 1980 book, Asheville: A Pictorial History, the new inscription read: “Our Army, Our Navy, Our Red Cross, Our War Workers, Welcome.” The victory arch remained standing until September 1920.

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

” salve is probably the least known Italian greeting (we never teach it to our students of Italian!) but a very useful one indeed. Salve comes from the Latin verb salvere (lit. to be well, to be in good health). It can be very friendly, e.g. Salve! Come va? (lit. Hi! How’s it going?), but on its own it’s also a polite form of greeting without being too formal. It’s very commonly used as a form of salutation, (in fact the word salutation itself comes from the same root: salute). So for example when you are out walking in the countryside and you meet somebody you don’t know salve is a very good alternative to buongiorno. Like ciao, salve can be used at any time of the day, but salve cannot be used when parting.”

https://blogs.transparent.com/italian/ciao-salve/

Learning either how to do a simple search for the meanings of a word in different languages (I mean come on, this was originally proposed right after a World War) or perhaps learning how ro be poite in differing languages — e.g. how t say hello and goodbye. Has society become so used to spoon fed news?

So the outrage police were going full throttle in Asheville a hundred years ago.

Interesting.

Only in the South would you have disgruntled resignations from a welcoming committee. But I give the ruling elite credit for pragmatic compromise in this case. The word “Salve” obviously had to be changed to “Welcome” in order to placate the ignorant hill-jacks, few of whom could speak Roman.