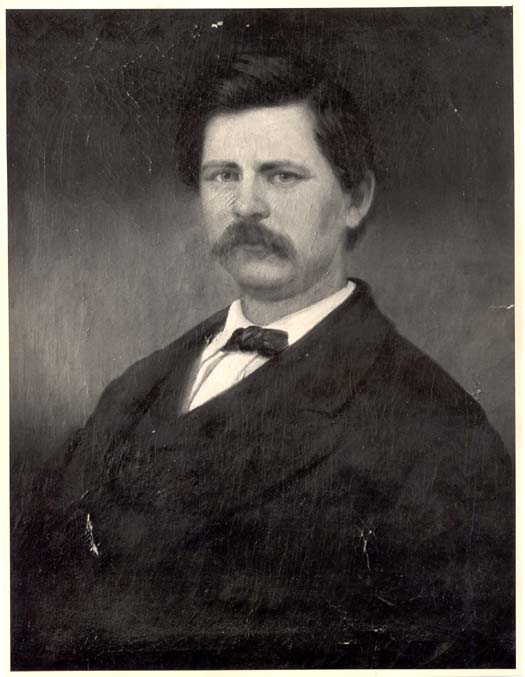

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Buncombe County native and wartime Gov. Zebulon Baird Vance was arrested by Federal troops. Held in prison for just two months, he was released in July 1865 and placed on parole.

During this time, in an undated letter to his friend John Evans Brown, Vance recalled the fall of the Confederacy. “Slavery was declared abolished … leaving four million freed vagabonds among us — outnumbering in several states the whites[.]”

Later in the missive, Vance rued the implications of emancipation. “There are indications that the radical abolitionists … intend to force perfect negro equality upon us,” he wrote. “Should this be done, and there is nothing to prevent it, it will revive an already half formed determination in me to leave the U.S. forever.”

Between 1865 and 1870, the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments were ratified, abolishing slavery, granting citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” and prohibiting the government from denying U.S. citizens the right to vote based on race, color or past servitude.

Despite his previous profession to flee the country under such circumstances, Vance remained. He was pardoned in 1867 for his role in the Confederate army. Though initially prohibited from serving in public office due to his past disloyalty to the country, he remained active in politics.

In the early 1870s, a bill introduced by Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts sought to outlaw racial discrimination in juries, schools, transportation and public accommodations. The proposed measure elicited many reactions, including those of former Gov. Vance, who addressed the House of Representatives on Jan. 10, 1874.

The North Carolina Citizen ran Vance’s speech in its Jan. 22, 1874, edition. In his opening remarks, the former Confederate rebutted claims that his opposition to the civil rights bill was based on hatred or prejudice. In fact, Vance declared: “I have felt it my duty to advance in every laudable way the interests of the colored race in this country.”

His opposition to Sumner’s bill, Vance asserted, stemmed from what he perceived as the legislation’s misnomer. It was not civil rights that the bill addressed, Vance claimed, but rather “social rights.”

He explained:

“There is no railway car in all the South which the colored man cannot ride in. That is his civil right. This bill proposes that he should have the opportunity or the right to go into a first-class car and sit with white gentlemen and white ladies. I submit if that is not a social right. There is a distinction between the two.”

The bill, he argued, would be “detrimental to the interests of both races,” stating legislation that outlawed discrimination would “rob the colored man … more or less of the friendship of the owners of the soil in the South.” Meanwhile, Southern schools, Vance noted, would close in the wake of mandated integration.

Another objection, framed as concern, turned into a long-winded rant about white supremacy. If the bill passed, Vance proclaimed, disharmony would surface between the races, which he considered an inherent disadvantage to African Americans. “No race, sir, in the world has been able to stand before the pure Caucasian. An antagonism of races will not be good for the colored man,” he stated.

In a similar vein, Vance argued the bill would create unrealistic aspirations among African Americans. “It begets hopes and raises an ambition in the minds of the colored man that can never be realized,” Vance declared.

Despite his efforts, Vance’s speech did not kill the bill. The following year, Sumner’s legislation was signed into law. Absent in the final version, though, was any mention of integrated schools. Eight years later, the Supreme Court declared the law unconstitutional, stating the 14th Amendment granted Congress the right to regulate the behavior of states, not individuals.

In 1877, Vance returned to the governor’s mansion for a third time. The following January, he attended a parade in Raleigh. The event featured several companies of African American troops who marched in celebration of Emancipation Day (see “Asheville Archives: Emancipation Day,” Feb. 27, 2018, Xpress).

According to the Jan. 10, 1878, edition of The Asheville Citizen, the governor was later invited to address a group of African American residents who were also celebrating the day.

Vance’s speech began:

“My Friends: — I appear in your meeting to-day simply to acknowledge the respect you have shown me by inviting me as the Governor of the State to visit your assemblage. You cannot of course expect me to join with you in celebrating this day, the anniversary of that emancipation which I struggled so long to prevent, and which I, in common with all the people of my race in the South, regard as an act of unconstitutional violence to the one party, and as an injury to the other.”

Nevertheless, Vance assured the celebratory group, “I should as Governor of North Carolina recognize you as citizens and should respect all the rights with which the laws have invested you.”

Editor’s note: Antiquated and offensive language is preserved from the original text, along with peculiarities of spelling and punctuation.

Sigh…..poor old Zeb makes an appearance again – actually, in all fairness, after a fairly long hiatus. That ought to re-energize the folks who want to demolish the Vance Monument, or at least rename it.

I’m surprised that the Usual Suspects haven’t set in to hollering already. I reckon with all the mess in our Nation today, perhaps for once folks are actually more engaged with the problems of the here and now?

I kind of wish Zeb had kept his threat and left the country…..then Asheville might have been forgotten about, and today be just another little quaint mountain backwater and Raleigh would still consider Statesville and Hickory as Western NC.

Yet, in 2019 we still have a monument to Vance in the center of Asheville. Most tourists probably believe that citizens must have enduring respect for a man so honored. How much longer will be tolerate this mistake?

I would bet my wig that most tourists might give it a passing glance but give it no thought whatsoever as they walk or drive by…too engaged with trying to avoid running over someone or being run over – and pretty much there for the touristy stuff rather than the history.

Hello, I’m doing a research project. I was curious where the author of the article obtained a copy of the Jan. 10, 1878, edition of The Asheville Citizen? (I had a hard time finding it when looking on the internet.) Thanks!

Hi Emma. I use newspapers.com to find these old editions for my articles. I hope your research project goes well.

Hello, I’m doing a school project, and I would like to know how you had access to Zebulons Vance’s original speech. (Doesnt exactly show up anywhere easily on the internet). Thanksm it would be a huge help :)

Hi Mathias, the majority of these remarks were found through newspapers.com. Some of the excerpts from from his letters were also pulled from Buncombe County Special Collections—if memory serves me right. If you go to BCSC, you should also be able to access newspapers.com for free. Thanks for reading.