Heather South, lead archivist at the Western Regional Archives in Asheville, has a theory. After years of gathering and collecting historical materials, she says, “I’ve become a firm believer that 90 percent of history remains in private hands.” Whether it’s letters, photographs, diaries, newspaper clippings, maps, meeting minutes or memos, experience has shown South time and again that individuals, families and businesses possess many of the things that archivists live to locate, document and file for posterity.

“Most of the time, people estate-plan for that heirloom piece of furniture or great-grandma’s quilt,” she explains. “But they don’t plan for their [personal and professional] records and photographs.” Instead, such items often get thrown out or stashed in boxes under unsuitable conditions. To an archivist, the former represents a tragic loss of resources, while the latter can damage valuable material.

Asheville is home to three primary repositories for such artifacts: Pack Library’s North Carolina Room, the D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections at UNC Asheville and the Western Regional Archives (an arm of the state Department of Natural and Cultural Resources). The individual collections they house may range from a single portrait to entire shelves’ worth of files. But archivists at all three facilities say there’s a need for more diversity in what’s on offer, urging community members to consider both their own legacy and how they might go about preserving it for future generations.

Making order out of chaos

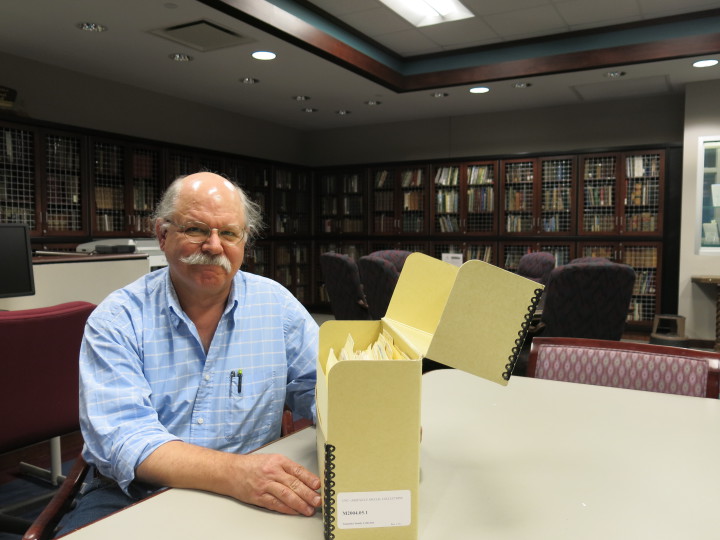

“One of the basic tenets of archival theory is that you try to respect the original order” the material came in, says Gene Hyde, Ramsey Library’s head of special collections. Too often, however, that’s easier said than done.

“Very rarely do archives come in any kind of order,” notes South. “That’s the exception to the rule.” But it’s not meant as a criticism. “You could probably go to my house and find letters in a drawer or on a bookcase,” she points out. “That’s what an archivist is supposed to do: put order to that chaos.”

This, though, takes time and resources, both of which are in short supply at all three local repositories. Each one has just two full-time staffers; and meanwhile, the Western Regional Archives houses 44 collections, D.H. Ramsey is home to an estimated 200, and the North Carolina Room has roughly 360.

Zoe Rhine, a special collections librarian at the North Carolina Room, recalls spending four hours just sorting a recent donation into piles. “Not folders: just stacks,” she clarifies. “There were stacks of scrapbooks, correspondences and photos.” Once that was done, it took a lot more time to arrange the items in chronological order.

Such experiences underscore the importance of taking a few simple steps, whether you’re a professional or just accumulating photos at home. Names, dates and locations matter. While Facebook might recognize a person’s friends and family members, archivists and historians don’t have that luxury when they’re trying to make sense of a new collection. Labeling files accurately and avoiding duplicated documents will help streamline the archivist’s work.

Enemies of preservation

What all of these places have in common is fluctuations in temperature and humidity. “That causes the deterioration,” South explains. “It speeds up the breakdown of the paper, the yellowing and the brittleness.” Ultraviolet light is also harmful.

Special collections maintain a steady 68 to 71 degrees with 30 to 50 percent humidity, but individual homeowners may not do that. The next best thing is consistency. “I always tease and tell people that under the guest bed is a perfect place” to store such items, says South. “One, it’s an interior room; two, it doesn’t get a lot of use; and three, there’s no light under the bed.”

But once you’ve decided where to keep your files, you need to consider what to keep them in. Acid-free paper is a must: Standard Manila envelopes are ideal, while standard copy paper works well for buffering. Cardboard, on the other hand, should be avoided: It’s highly acidic and will leach into files.

South also encourages people to store their papers flat rather than folded. “Paper fibers are woven,” she explains. “When it’s folded, it weakens those fibers.” And if circumstances don’t permit flat storage, South recommends rolling the documents.

Hyde, meanwhile, offers this additional advice: “Don’t get your stuff wet. If you do, dry it thoroughly. Mold is the bad one. Fire is a bad one, too. But probably the worst are dirt and mold. Insects can also be bad; rodents, silverfish. There’s a whole range of things that can be introduced into materials if they’re not stored in good condition.”

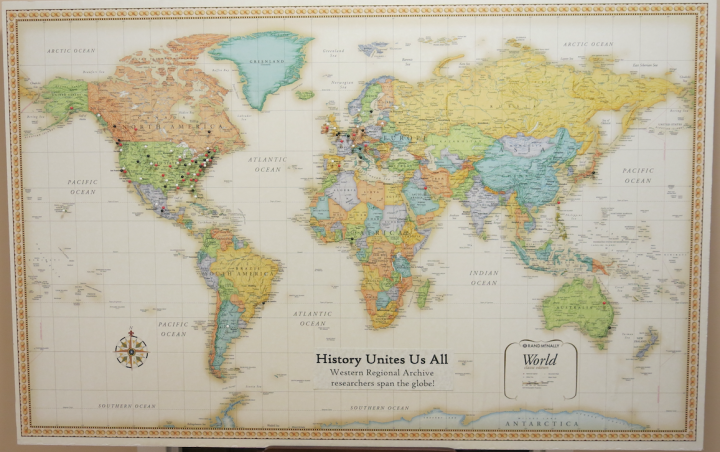

Around the corner and across the globe

At the Western Regional Archives’ third-floor headquarters, a world map, peppered with pushpins, greets guests as they enter. Each pin represents a specific place from which a visitor has come. Of the seven continents, only Antarctica is pin-free. Most international travelers, notes South, are there to access the archive’s largest collection: Black Mountain College. When the pioneering art school shut down in 1957, the state became the custodian of its official records. Before the Western Regional Archives opened in 2012, those files were kept in Raleigh. “They were so out of context there,” says South. “By bringing the collection back home, there’s been this elevation of use.”

On average, the Western Regional Archives sees about 2,000 visitors per year, with 4,000 to 5,000 inquiries submitted by phone, fax, email or letter. The North Carolina Room averages a combined 4,000 annual visits and inquiries. About a third of those visitors, says Rhine, are from out of town.

Economic impact studies haven’t specifically looked at special collections, but a 2014 report commissioned by the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area Partnership, notes South, found that heritage tourism brings $2.39 billion to the region annually. “We are contributing to the local economy by people coming specifically to do research in our collections,” she points out. “It’s heritage tourism in a lot of ways.”

The rest of the story

To maximize the value of those holdings and do justice to the region’s rich history, however, archivists at all three repositories say we need to fill in some pretty big gaps. “The common perception of Appalachia is that there aren’t African-Americans,” says Hyde. “There’s this misperception that Appalachia was all settled by white people from the English islands. That’s not true.”

One of Ramsey Library’s first collections, he notes, was its 1977 Heritage of Black Highlanders acquisition. More recently the library received the Isaiah Rice Photograph Collection: a series of images depicting Asheville’s African-American community from the 1950s through the 1970s. Nonetheless, Hyde sees a need to more fully represent the experiences of both black Ashevilleans and the local Greek community.

Rhine is on a similar mission. In the past, Pack Library’s special collections focused mostly on processing whatever items happened to be donated. But in recent years, Rhine has been reaching out more to various groups in hopes of enhancing the archive. She’s used roundtable discussions and oral history projects to help the community connect with the North Carolina Room’s holdings.

Like Hyde, Rhine is trying to fill in what’s missing. “Our photographs and postcards cover all of Western North Carolina, but in the past, most of the material that was donated to us … basically represented white middle- and upper-class residents.”

Besides collecting historical documents concerning underrepresented residents, Rhine is actively working to research and preserve the stories of Asheville’s LGBTQ community. To this end, the North Carolina Room recently partnered with David Dry, a history instructor at A-B Tech. Dry, says Rhine, started out by getting his students up to speed on oral history, how to make transcripts and the local gay community. After that, she says, “Students paired up and interviewed people, transcribed it and came back to us as a turnkey project. … I think it took people out of their small circle, introducing them to people they wouldn’t have known, of a way of life they might have viewed through stereotypes.”

Building trust

Even with the best of intentions, however, interviewers and archivists will inevitably confront barriers that must be broken down.

Sheneika Smith founded Date My City in 2013. The social organization aims to enhance the cultural identity of black communities in WNC. The first step in building trust between different populations, she says, is promoting “dialogue with people who are lovers of history, in a diverse setting.” Smith also stresses the importance of being clear about a project’s purpose. Distrust, she notes, may stem in part from having seen the community’s experience misrepresented or misused in the past. “The last thing we want to do in communities of color is allow our stories … to be romanticized or just a pony show.”

Roy Harris, a retired engineer who arrived in Asheville in 1983, recently joined the board of the Friends of the North Carolina Room. “Being an African-American, I would like to make sure that the African-American stories are also told and collected,” he explains. Harris sees himself as a kind of ambassador, part of whose role is to get out into the community and let folks know what the facility has to offer — whether it’s free access to ancestry.com and newspapers.com or a paper trail that might shed light on “questions that they’ve been pondering for months,” he says.

But Harris encourages everyone to share their stories. “The Native Americans, the Latinos — all the cultures.” Their history, he says, “is out there somewhere.”

Smith shares Harris’ sense of the urgency of creating a more inclusive historical narrative. Besides filling in the past, it helps foster unity among different groups today. “I think history has always been a guide,” she points out. It can provide “rules of engagement, as far as how to handle conflict in communities, or just problems that might not be internal to your community but externally affecting your community.” In this way, she explains, history can “show communities patterns of injustice but also stories of triumph.”

Cultural amnesia

Over at the YMI Cultural Center, administrative assistant Tonia Plummer says she’s seen a kind of cultural amnesia concerning Asheville’s African-American history. When school groups come to tour the building, they often know nothing about the neighborhood’s history. “They were never told that this was totally an African-American business section.”

Plummer, who grew up in Old Fort, remembers visiting Asheville on weekends. “You could stay here on Saturday afternoon and get everything you needed in this one area called ‘The Block’: your hair cut, beauty shops, go to the theater, restaurants. They even had clubs, gas stations, a drugstore, the ‘colored library.’”

To help address this, the nonprofit is gearing up to create its own archived repository of donated items. “I’m hoping the YMI will eventually become a place where people can come and look at our collection,” she says. The organization is currently seeking help to organize its material.

The collection, says Plummer, should focus not on the city but on “the individuals who inhabit the city: That’s where the greatest stories are going to be told. That’s where you’re going to find out about how people lived and what they did. There are some interesting people in this world: I’ve run into a few at the YMI.”

History’s lessons

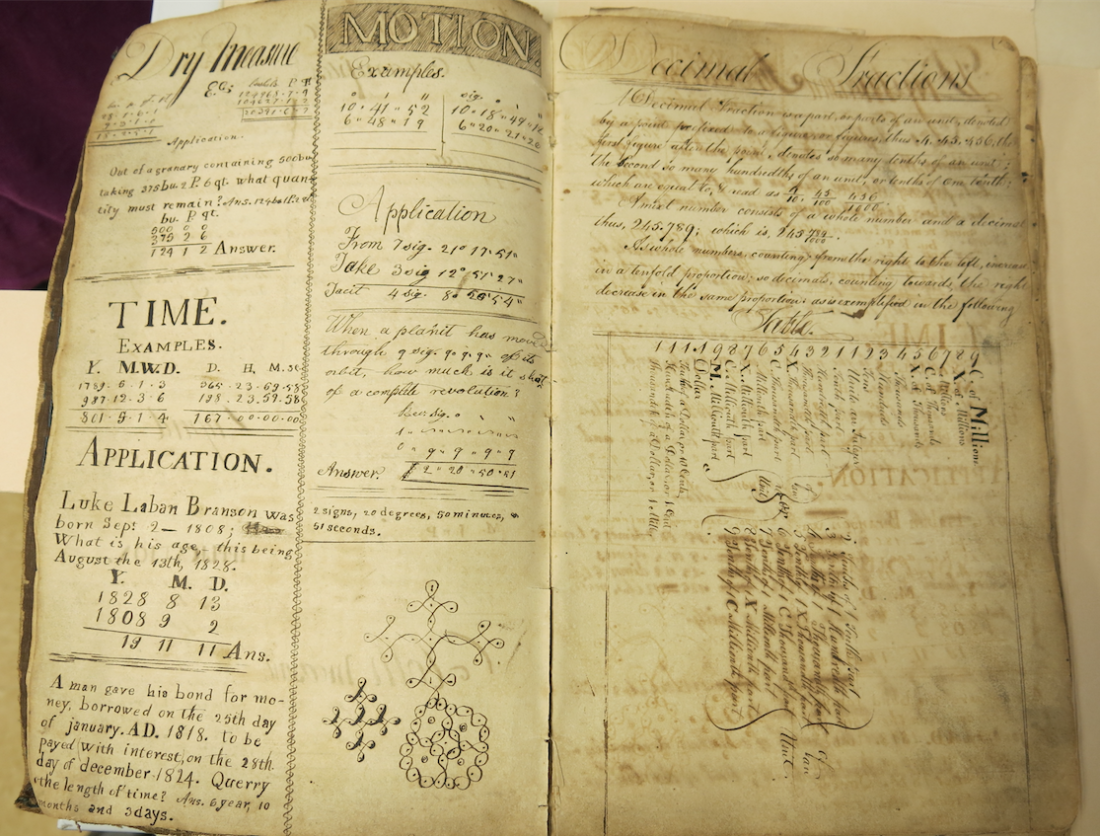

All of Asheville’s special collections include items that have somehow managed to survive for centuries. The oldest materials — land grants, guest ledgers, letters, diary entries and books — date to the 1700s. At the other end of the spectrum, there are digital recordings, videos and oral histories.

Researchers often start at one collection and find their way to the next as they follow the thread of their investigation. But these organizations’ shared sense of purpose encourages cooperation. “I don’t care what repository donations go into, as long as they’re being cared for and documented,” says South.

Hyde agrees. “We always like to get a call from someone who has an interest in possibly donating something,” he says. “It may be something that fits our guidelines, or it may be something we’d refer to Pack or to Western. But it’s important, if people think they have something that might be valuable, to check with an archivist at one of these collections.”

Rhine, meanwhile, encourages people to take the first step. “Don’t put it off: If you’re willing to donate, just bring it to us” (see box, “Starting Points”).

You don’t have to be a history buff to benefit from these collections, either, stresses South: The archives offer universal lessons. “I learn new things every day,” she says. “I may look at the same box 12 times, but because I’m looking at it through different people’s requests or interests, I see it differently. There’s something amazing in that. It’s a privilege. … I think that if you look at history through these different lenses and different points of view, you become more open-minded.”

Excellent article. Much needed.