Having worked on the estate for 37 years, lifelong Asheville resident Bill Alexander knows his way around the Biltmore House and its grounds. As landscape and forest historian for the Biltmore Company, he’s responsible for researching, preserving and sharing the extensive story of the estate’s unique natural setting.

Two years ago, Alexander began working on his latest book (his two previous titles focus on the Biltmore plant nursery and Biltmore Village). This time out, his subject is the gardens and grounds of the Biltmore Estate: how they were conceived, executed and maintained through the estate’s history. Along the way, we catch glimpses of early environmental awareness, innovative labor practices and the simple enormity of the task undertaken by George Vanderbilt and the team responsible for the mature landscape we see at Biltmore Estate today.

Early days

Visiting Asheville with members of his family in the winter of 1887 and 1888, George Vanderbilt conceived a fancy that would be familiar to many tourists of today: he liked the area so well, he decided to buy some land here. According to Alexander, an area just to the south of Asheville near a railroad station caught Vanderbilt’s eye.

Alexander quotes the young scion’s later remembrance of his first introduction to the area: “I took long rambles and found pleasure in doing so. In one of them I came to this spot under favorable circumstances and thought the prospect finer than any I had seen. It occurred to me that I would like to have a house here.”

After returning home to New York, the energetic bachelor wasted no time in assembling a top-notch team of designers and advisors. While the names of architect Richard Morris Hunt and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted are the most famous associated with the project, Vanderbilt’s friend and attorney Charles McNamee played a critical role in the early formation of the estate.

McNamee moved to Asheville and began assembling parcels of exhausted farmland, overgrazed fields and scruffy wooded areas. He purchased many of the tracts under his own name, so that land prices would not be inflated as landowners became aware of Vanderbilt’s intentions. By the end of 1890, McNamee had acquired about 6,000 acres. In time, that area would grow to nearly 125,000 acres.

Making a plan

Alexander’s text, along with carefully chosen photos from a number of archival sources, illuminates the surprisingly strong influence Olmsted exerted over Vanderbilt during the planning of the estate. While Vanderbilt initially envisioned a formal park — similar to those he had seen in Europe — stretching from the Biltmore House to the French Broad River, Olmsted bluntly countered that vision with a more realistic plan: “You bought the place then simply because you thought it had a good air and because, from this point, it had a good distant outlook. If this was what you wanted you have made no mistake…[But] It’s no place for a park. You could only get very poor results at great cost in attempting it.”

Instead, Olmsted counseled, Vanderbilt should create “a small pleasure ground and garden” close to the house, while making the rest a forest. Olmsted called this course of action “a suitable and dignified business for you to engage in.” Thus were the seeds of the nation’s first formal program of forest management sown, eventually resulting in the establishment of the Biltmore Forest School.

Along with Olmsted’s early advice regarding the most suitable uses for Vanderbilt’s Asheville property, Alexander’s book makes clear how extensive and methodical were the design and planting techniques used by Olmsted and other designers to create the pastoral, naturalistic effects of the estate’s landscape, especially on the Approach Road, the Spring Garden, the Glen, the Bass Pond and the Deer Park. A strong environmental sensibility also comes through the text and photos, showing that the estate’s creators were concerned with preserving habitats for wild animals and birds, and with improving the depleted environment that had been previously damaged by overuse.

Huge undertaking

The book also touches on the many workers whose efforts contributed to shaping the vast estate. Superintendent Chauncey Beadle gets a whole chapter for his 60 years of service. Beadle’s contributions and capabilities were many: he collected and propagated a vast amount and variety of plant material used on the estate, assisted George and Edith Vanderbilt with business and personal matters, served as landscape architect for the development of the town of Biltmore Forest and published several works of botany.

Alexander summarizes: “The list could go on, but perhaps most importantly, Beadle was the common denominator, the continuum that spanned more than a half century of Biltmore’s operations from the establishment through the founder’s death, two world wars, the Great Depression, the changing of the guards in the Olmstead firm, and beyond.”

A reader might wish one intriguing photograph were larger: an image showing the landscaping department on a break from their work on the Approach Road in 1891. The photo shows an integrated workforce of white and black laborers standing shoulder to shoulder with Beadle and Vanderbilt. In an interview, Alexander remarks that the landscaping crew on the estate was one of the very first, if not the first, integrated workforces in the South.

Those fascinated to learn how large projects were accomplished in earlier times will enjoy reading about the railroad spur laid to transport materials to the building site, the on-site quarry, the construction of a brick and tile factory (supplied by clay pits on the estate) and the engineering associated with building roads, ponds and the Lagoon.

Images of America

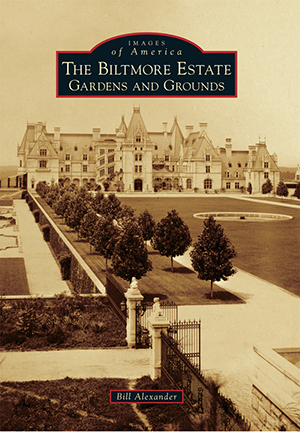

Alexander’s book is part of the Images of America series, published by Arcadia Publishing of Charleston, S.C. This series connects local authors and historians with local audiences to preserve and pass on local history traditions. The format of the softcover books lends itself to browsing, with two captioned black-and-white photos on nearly every page.

That photo-driven format is both a strength and a weakness of the series: the layout is easy to flip through, but its captions don’t lend themselves perfectly to reading in a longer sitting. As a compromise between a narrative text and a coffee table book, the series offers authors a convenient way to provide historical information and readers a reasonably-priced and approachable way to access it.

For Asheville residents and visitors familiar with the Biltmore estate, The Biltmore Estate: Gardens and Grounds offers an opportunity to pick up some new facts about the endlessly-fascinating story of the property. The book retails for $21.99 and is available at Malaprop’s Bookstore in downtown Asheville, as well as at Barnes & Noble and online booksellers.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.