Priscilla Brackett’s inability to communicate while under stress cost her a favorite pair of jeans. She considers herself fortunate that it didn’t cost her more.

Brackett has autism, as does her 12-year-old daughter, Evelyn, and both tend to lose verbal abilities when under stress.

“I had been in an accident, and I injured my knee,” Brackett recalls. “But I couldn’t communicate that the injury wasn’t too bad, so they cut my pants to examine my knee.”

A new app that’s about to start a trial in the Buncombe County Schools could help first responders understand such invisible disabilities.

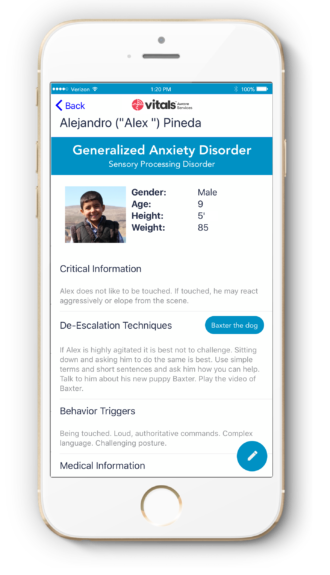

The Vitals App displays critical information about a person on the phone where it’s installed whenever that phone comes within 80 feet of someone wearing or carrying a beacon. The watch-sized Bluetooth device broadcasts the information to the app, which displays it on the phone. When the first responder walks away, the information disappears back into the cloud as soon as the phone is 80 feet from the beacon. In the meantime, however, the information displayed might help a first responder deal with someone who’s nonverbal or agitated. It might indicate that the person has an aversion to being touched, for example, or perhaps offer tips on how to calm the person down.

This fall, two Buncombe County high schools — T.C. Roberson and A.C. Reynolds — will begin using the app, making this the first school district in the country to try it out. Developed by a Minnesota company called Vitals Aware Services, the free app is currently being used by 65 police departments there, the company reports.

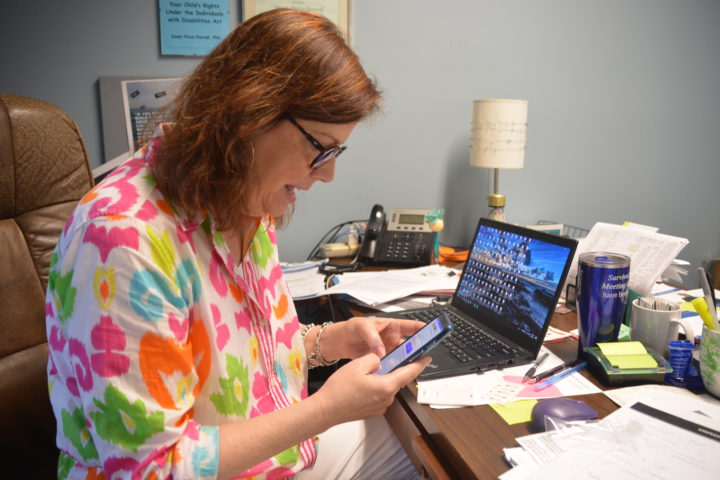

FIRST, an Asheville-based nonprofit that serves children and adults with special needs, is collaborating with the schools and the company. On a recent morning, Executive Director Janet Price-Ferrell was working on the profile for her adult son, Austin, who has seizures that don’t manifest in typical ways. When he’s having one, he can become extremely agitated.

“Not everybody knows that he threw a chair across the cafeteria once,” she explains. “A policy of inclusion is great until the behaviors start. This app can help people understand the behaviors of people with invisible disabilities.”

Brackett agrees, pointing out that significant numbers of people with invisible disabilities have been injured or killed by police who didn’t realize that the person couldn’t comply with their instructions.

Averting tragedy

According to a 2016 report by the Ruderman Family Foundation, which advocates for people with disabilities, such incidents may account for as many as half of all police fatalities.

“Disabled individuals make up a third to half of all people killed by law enforcement officers,” the executive summary concludes. They also “make up the majority of those killed in use-of-force cases that attract widespread attention. This is true both for cases deemed illegal or against policy and for those in which officers are ultimately fully exonerated. … When we leave disability out of the conversation or only consider it as an individual medical problem, we miss the ways in which disability intersects with other factors that often lead to police violence. Conversely, when we include disability at the intersection of parallel social issues, we come to understand the issues better, and new solutions emerge.”

Lisa Adkins, executive director of the Buncombe County Schools Foundation, sees the app as an example of such solutions. She learned about it on the Facebook page of a friend and former colleague and decided to investigate.

“It was so serendipitous,” she says. “When you’re looking at it from the perspective of a foundation, you want to be certain it’s an effective use of your money, and I believe this is.” Although the app itself is free, additional beacons cost $20 apiece.

David Thompson, the district’s director of student services, says the app will be made available only to key school personnel such as nurses and resource officers, and participation in the program is completely voluntary.

“Even if a school resource officer knows every child in the school, they might not know what they need to know about every child,” notes Thompson. “This can help us in emergencies, and it can help us avoid some things becoming disciplinary situations when they don’t have to be.”

The information the beacon transmits to the app is programmed by parents (or, in the case of adults, by either the person with the disability or a caregiver). In addition to important details about the disability, it can include things like video of parents assuring a child that all will be well.

“In the school setting, parents create the profile. They share only what they’re comfortable sharing,” stresses Thompson.

Saving lives

Sheriff Quentin Miller is reserving judgment on the app until he’s seen it in action, says department spokesperson Maj. Randy Sorrells. Miller, says Sorrells, has been meeting with school officials to learn more.

Angela Ledford of Buncombe County Emergency Services is also taking a wait-and-see approach. Although she hadn’t heard of the app, “There is potential for it to be helpful,” she says, adding, “I want to see it in action.”

Brackett, though, says she needs no demonstration. Both she and her daughter tend to shut down under stress, and things like fire and active shooter drills at school can cause Evelyn to panic.

“It’s especially unnerving when it’s realistic, like when somebody rattles the door to the classroom,” notes Brackett.

School personnel now inform Evelyn before a drill, so she can be more prepared. But while her teacher and certain others know about Evelyn’s condition, an emergency responder might not, meaning she could become a statistic if she didn’t follow instructions or answer questions properly.

“I just remember what happened when an autistic man with a toy car encountered police a couple of years ago,” says Brackett.

In Miami in July 2016, Charles Kinsey, an unarmed behavioral therapist who was caring for a man with autism, was shot by a police officer. The officer thought Arnaldo Rios Soto had a gun; it turned out that he had a toy car, and Kinsey was trying to calm him when he was shot. Kinsey survived, and the officer was found guilty of a misdemeanor.

The app can also help with people who have other issues, such as diabetes or dementia. It can alert first responders to the fact that this particular unconscious person needs insulin or sugar, or tell them whom to contact concerning a person with dementia who’s found wandering around downtown alone.

“I saw the potential in this as soon as I heard about it,” says Price-Ferrell. “I think it’s a great idea. It has the potential to save lives.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.