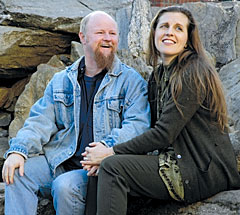

photo by Mariah Grant

A love that dares speak its name: Marc Eden (left) was born Mary Eden. After transitioning from female to male, he found acceptance and a mate in his wife, Chrysse Everhart.

|

Swannanoa resident Marc Eden remembers his last night as Mary Eden. He sang soprano in the final performance of A Chorus Line in Billings, Mont., in April 1986.

The next day, Eden had his first injection of testosterone, a move he’d delayed until the production ended so his voice wouldn’t deepen. Mary’s breasts were removed then, too, because of fibrocystic disease and a family history of breast cancer. The doctor didn’t know about Mary’s plan to become Marc, which was a big factor in pursuing the surgery.

But Eden’s transition from female to male was much more gradual, spanning many years and incremental steps: secretly hoping each Christmas that God would make Mary a boy; dropping out of a roller-skating contest in Montana because the officials would not let Mary wear men’s slacks instead of a short skirt; studying the mirror late at night while the rest of the family slept to watch shadows give the appearance of facial hair.

“In the dim light of the night, that’s when I could see me again. I don’t know how many nights I spent just trying to see who I was in the mirror,” says Eden, now 40.

Other transsexuals also report turning to the mirror to search for their real selves. And, like Eden, some choose to pursue the image they see in the glass.

“Transgender people shouldn’t have to hide. Nobody should have to hide who they are,” says Jessica, a male cross-dresser in Asheville who came out after years of shame and occasionally purging women’s clothes, wigs and makeup from the closet.

Around the country, more transgender people — including both transsexuals like Eden and cross-dressers — are coming out of hiding, and transgender characters are being seen in television shows and movies. Asheville’s growing transgender community now includes an estimated 200 people, according to one community leader. And Phoenix, a transgender support group formed here in 1986, is among the oldest such organizations in the Southeast.

A hidden land

Unlike homosexuality, which is a matter of sexual orientation, transgender involves an individual’s perception of his or her gender (which may be female, male, both or neither). Transgender people may be gay, heterosexual or intersexual (having both female and male characteristics). Cross-dressers, usually heterosexual men, wear clothing associated with the opposite gender, sometimes for sexual gratification.

Despite signs of increasing tolerance, however, the transgender path often entails anxiety, fear and confusion. But some people find relief in pursuing their real identity.

“They’re desperate for a home and for the ability to be who they are without judgment,” says Dr. Bruce Kelly, a family physician who, in a former private practice in Asheville, had transgender patients. “Many had considerable anxiety, feeling disenfranchised or embarrassed or isolated. Just like all of us, they want to be accepted.”

But for many transgender people, the desire for acceptance becomes an obstacle that drives them to hide their cross-dressing for years or try to fill the traditional roles of their sex at birth.

For Eden, frustration over living as Mary culminated in a night of binging on drugs and alcohol while in college. Fearing that his heart would stop, Eden made a pact with God that if he lived through the night, he would move forward with the transition. “I am on the bottom. There is nowhere else to go,” Eden told himself.

His youth in Las Vegas had been a painful duality: living as a girl but wanting to be a boy. Photographs show him as Mary on girls’ soccer teams; with a choir in a blue dress; in a satiny white gown for the senior prom. As a teen, Mary imagined herself as the male during sex with boys.

“Right up until transition, I was out to prove myself as womanly as anyone,” Eden recalls. “Being fundamentalist, anything else was not an option.”

But one day, Eden found another option when he saw a television show about sex changes. Later came the testosterone injections that lowered Eden’s voice and added hair to his face and chest. Today he is balding and has a beard.

While Eden was growing hair, “Carol” (not her real name), who was born male, was losing her masculine traits thanks to estrogen, which softened her skin, enlarged her breasts and decreased her muscle mass.

The 55-year-old, who lives in the Asheville area, began cross-dressing as a boy, aware of feeling different — prone to crying over books and movies, and caught up in romance more than most boys. “When you’re a kid and you don’t have language for it, you just know it’s not normal,” she says. Carol secretly cross-dressed through her first marriage.

“It was a given [that] this had to be my private thing, a hidden land. You cross a border … and know you have to come back,” says Carol, who works in sales. “It had always been a given that I had to hide things and lie about things.”

A lot of the lying and hiding stopped when Carol came out about her cross-dressing in subsequent relationships, including another marriage. Her second wife didn’t mind the cross-dressing — in private. Agonized by being restricted, however, Carol began to transition when she was in her 30s, taking estrogen and living as a woman full time. Eventually she legally changed her name; before her second divorce, she had a son.

Funny looks

photo by Jon Elliston

Mutual support: Zeek Christopoulos, at right, began transitioning from gal to guy in his late 20s. Here he helps coordinate a recent meeting of Tranzmission, a transgender-support group composed mostly of young people.

|

Some cross-dressers choose not to pursue transition. Jessica, 51, a bookseller, uses her legal name (Jeff) and wears typical men’s clothing on the job. She gets no sexual thrill from dressing as a woman, a habit since she was a teen wearing her mother’s clothes. She’s just more comfortable that way, she says.

As Jessica, she wears a bra over silicone breast forms; women’s underwear, skirts and slacks; women’s size 10 or 11 shoes; pantyhose; clip-on earrings; lipstick, blush and mascara; long hair down and loose. She still shaves her face — and her arms, legs and chest. And she softens and raises her voice.

Divorced, Jessica says she’s more attracted to women than men, and she’s started thinking about living as a woman full time, because it might be easier. In restrooms and other public places, she notes, “Jessica doesn’t get funny looks; Jeff does.”

Zeek Christopoulos knows something about funny looks; he moved to Asheville from Florida partly to avoid getting them from people who knew him while he made his transition to a man (or a “trans guy,” as he calls himself). And though he considered himself a lesbian before he began the transition in his late 20s, he had a different idea as a girl named Sondra.

In a taped conversation with his mother, Christopoulos, then about 2 years old, said he wanted to be a boy when he grew up. Today, his masculine appearance is enhanced by testosterone injections, which give him a full beard, and $7,000 worth of chest-reconstruction surgery.

And though he experienced turmoil while deciding whether to pursue hormone therapy and surgery, Christopoulos says he’s more comfortable with his body — and himself — these days. “Before, I never could blend in,” he reveals. Now 33, he remodels homes and does odd jobs.

Not all transgender people want to assimilate, however. Some “feel that we are here to help people see things,” Christopoulos maintains, “not to be limited, restricted or categorized.”

To that end, he and other mostly younger transgender people formed Tranzmission. Group members talk to health-care professionals, college classes and others about transgender. And members of Phoenix, whose meetings draw people from several states, do similar outreach.

Us and them

Historically, the relationship between transgender people and gays has not been close. That may be partly because the two groups have somewhat different issues. A common focus for transgender people, for example, is “passing” (being accepted as the opposite sex). But some gay men are turned off by male-to-female transsexuals, whom they consider too feminine, explains David Gillespie, who is gay. And though he’s the editor of Out in Asheville — a monthly publication for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities — his comment doesn’t represent the paper’s position.

But proposed national hate-crimes legislation may signal a stronger link between the two communities. In September, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Local Law Enforcement Hate-Crimes Prevention Act as an amendment to the Children’s Safety Act; a companion bill has been introduced in the Senate. For the first time, transgender Americans would be protected along with gays, lesbians and bisexuals.

That’s significant, because legislators and gay activists alike had long maintained that including transgender people as well as gays in a hate-crimes law would hurt its chances of passage, notes Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality in Washington, D.C. And though the Senate bill doesn’t explicitly include transgender people, Keisling thinks there’s a good chance the final version will. “I know that the radicals are going to try to stop it,” she says. But “the House vote showed that members of Congress are willing” to include transgender.

Meanwhile, 10 states have already passed hate-crimes legislation that covers transgender people, she reports — a sign of growing acceptance of a group Keisling’s organization estimates at no more than 1 percent of the population.

Not everyone approves of such laws, however. “They should not be given special protection,” proclaims Jere Royall of the North Carolina Family Policy Council in Raleigh. “We should not be looking at a group of people based on behavioral questions.”

And though some polls have indicated that North Carolinians may be more supportive of transgender now than in the past, the state has no laws to protect transgender people from discrimination in housing and employment, reports Ian Palmquist of Equality NC. The Raleigh-based group advocates for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people.

Meanwhile, violence against transgender people persists. On average, one transgender person a month has been killed since 1990 in the United States and other countries, according to Remembering Our Dead, a Web project that logs incidents of anti-transgender violence. And in 2004 alone, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs recorded 1,792 incidents of violence against 2,131 people who were lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or HIV-infected. Of the victims, 11 percent, or 234 people, were transgender.

Tough row to hoe

Transgender people face other hurdles, too (see “Making the Change”).

While breast reduction and enhancement are not uncommon among transsexuals, few pursue genital surgery, partly because of the cost, says Keisling.

And hormone therapy (using estrogen or testosterone) carries health risks. Some people who use hormones or see health-care professionals for other reasons say they’ve had to teach the doctor about transgender medical issues. In addition, some doctors balk at treating transgender patients, including female-to-male transsexuals who need gynecological care.

“There’s the initial sort of shock value of realizing this woman standing in front of you is actually a man,” says Dr. Kelly. “Physicians tend to not want to provide care where they don’t have a comfort level with what they’re treating.” It took him awhile to be comfortable helping male-to-female patients with estrogen, a procedure in which most doctors aren’t trained.

Employment poses challenges as well. Some transgender people say they’ve been fired from jobs in Asheville after their employers found out about them, and many agonize over whether or when to tell their employer. Factor in denial, anxiety about rejection, fear of being harassed and conflict about whether to transition, and depression is not uncommon, according to mental-health professionals.

Some local transgender people also report having hired lawyers to help them change their name because of resistance they say they faced in the process. Once people file paperwork for a name change, cases are assessed individually. The clerk of Buncombe County Superior Court “has to be satisfied that it’s for good cause, and that’s totally in the clerk’s discretion to say if it’s good cause,” notes Assistant Clerk Richard Schumacher.

Live and let live

One of the toughest aspects of transgender life is rejection. Some lose longtime friends or are cut off by family. Carol’s family, for example, told her she wasn’t welcome at her own mother’s funeral.

Not everyone reacts that way, however. Jessica’s daughter, Susan, for example, knew about her father’s cross-dressing at an early age and says she was never bothered by it. She even played with his makeup and perfume.

“He does make a very beautiful woman,” notes Susan. “I can probably think of him either way, but he’s my dad. That’s the most important thing right now,” says the 20-year-old Asheville resident.

And Chrysse Everhart, a nontransgender woman who married Eden in Las Vegas in 1994, observes, “If you really love someone, something like their gender or their body parts can be surmounted.” Everhart, now 42, learned Eden’s history about six months after they started dating. After more than 10 years of marriage, she says, “It can be just another facet of who they are, and it can be appreciated.”

Eden, meanwhile, has come a long way from the uncomfortable-looking girl in a choir dress in childhood photos. When he had a hysterectomy at Mission Hospitals, the doctor put him on the oncology floor, so that both Eden and the other patients would be more comfortable.

In Asheville, he works as a nurse and has been involved in a choral society, a theater group and a men’s soccer league. Eden’s biggest challenge, however, is whether to come out to people he meets.

“In these hills, there’s a live-and-let-live attitude that’s as old as the hills themselves,” says Eden. And some folks have said they admire him for being who he is.

Eden also believes that face-to-face education will help increase acceptance of transgender people. “That’s the only way there’s going to be equal footing,” he says. “You change people one by one.”

[Freelance writer Jess Clarke is based in Asheville.]

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.