|

|

|

recent photos by Jodi Ford

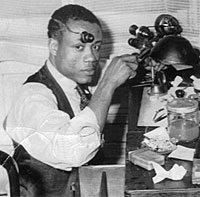

Looking back: Viola Jones Spells and Marvin Chambers shown today and in their yearbook photos from high school. Both were members of ASCORE who participated in sit-ins and other actions to combat segregation in Asheville.

|

|

|

|

|

When four African-American college students walked into a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, N.C., and sat down at the “whites only” lunch counter on Feb. 1, 1960, they sparked a sit-in movement that spread like wildfire. Within months, similar protests were staged in dozens of other cities, mainly in the South.

There was no black college in Asheville whose students could take up the cause. But a group of politically active friends from the all-black Stephens-Lee High School rose dramatically to meet the challenge. “We … felt very strongly that we wanted to be a part of correcting the injustice that the sit-ins were directed [at], so we started organizing ourselves,” explains James Ferguson, the first president of the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality.

Over the next five years, ASCORE achieved remarkable success as these committed young people dismantled the color bar in restaurants, movie theaters and assorted other public facilities in Asheville. Not content with opening those doors, however, they also created new job opportunities for black workers. And to ensure continuity, they even recruited their own replacements before moving out into the wider world of college and careers.

A Nov. 6 awards ceremony organized by the Center for Diversity Education will honor the spirit of these courageous young African-Americans, who were instrumental in changing the face of Asheville (see “Honoring ASCORE” below).

Learning the ropes

The Greensboro protests may have provided the immediate inspiration, but the core of what would become ASCORE — Charles Bates, James Burton, Jayne Burton, Marvin Chambers, Burnell Freeman, Patricia Geer and Ferguson — was already attuned to the emerging civil-rights movement. The group had been working on getting facilities at Stephens-Lee that were equivalent to the ones at the all-white Lee Edwards High School. The young activists had also been attending Sunday-afternoon meetings of the Greater Asheville Interfaith Youth Council at the old YWCA on Grove Street, where they could hold frank discussions on racial issues and other topics with white kids their own age.

They also began enlisting the aid of adults in the community. “Some of them agreed to help; there were others who were fearful for our safety and preferred that we not do it,” says Ferguson. “But we were determined.”

Among the adults who mentored and supported the group were Rosetta Hill, a teacher at the all-girl Allen High School; the Rev. Niolus Avery; Leah Butler, the wife of a local dentist; Lloyd McCoyd, a retired railroad worker; and Ruben Dailey and Harold Epps, Asheville’s only African-American attorneys at the time. In the years to come, other adults also stepped forward to help the group.

photo courtesy Center for Diversity Education

Guiding light: William Roland, owner of Roland’s Jewelry on Market Street, was a key mentor to the student members of ASCORE and also provided them with meeting space in the back of his store.

|

But the strongest supporter, says Ferguson, was local jeweler William Roland. “He, more than anyone else, worked with us, had patience with us, trained us, listened to us,” Ferguson recalls. “He was just there.” The young activists soon began meeting after school in the back office of Roland’s jewelry store on Market Street.

Beyond his immediate personal impact, Roland’s commitment to nonviolence and connections with the American Friends Service Committee also greatly influenced ASCORE’s approach. The group, says Ferguson, “soon realized that instead of just going downtown to have a sit-in, we needed to learn more about the nonviolent method. So we attended seminars, got literature, [met with] representatives from the American Friends Service Committee [and attended meetings] in Raleigh and other places.”

The name ASCORE was a tribute to the Committee of Racial Equality (the name was later changed to the Congress of Racial Equality), a national civil-rights group that spearheaded the lunch-counter movement. Another Ashevillean, Floyd McKissick, became CORE’s national director in 1966. (In 1951, as a result of the federal court case McKissick v. Carmichael, he and four other students had become the first African-Americans to attend the University of North Carolina Law School.)

ASCORE, meanwhile, had started recruiting other students. One of them, Viola Jones Spells, remembers being impressed by how organized the group’s meetings were. “Mr. Roland’s office was a very tiny space, and we were all huddled in the back discussing what we were going to do, how we were going to do it, just planning and strategizing at a very young age,” she recalls. “We would make a list of all the places we thought needed to be targeted and then we would prioritize them, and then certain people were assigned to committees: who would sit in the lunch counters, who would be on the committee to go and negotiate opening up some of the public places.

“I felt great that I was a part of something like that, and I really feel honored that my parents allowed me to be … because during those times, it was very scary,” she notes. “A lot of my close friends were not [allowed to] be involved.”

Standing up by sitting down

The first issue ASCORE tackled was desegregating local lunch counters. Initially, the group tried negotiating with the owners, but when that didn’t work, the focus shifted to direct action. The sit-ins took place mainly in downtown Asheville at the Kress and Woolworth lunch counters and at Newberry’s, where African-Americans were restricted to ordering from the takeout window.

The sit-ins were frightening, says Spells. “You were breaking the norm, and also the [white] people were pretty mean. … They said some pretty nasty things to you.”

But some whites were sympathetic to the cause, recalls Chambers, another one of ASCORE’s founders. “When we went down to Woolworth’s and Newberry’s and Kress … we were told … to leave a seat vacant between us, because there would be [a white person] who would come and sit there and not to become alarmed,” he says. “We wouldn’t know who these people were — maybe some of the advisers may have known — but they were on our side and they were with us, which helped us a lot.”

Chambers also vividly remembers the time “we went to a drugstore one Sunday afternoon, and we sat down on the stool and the pharmacist came out and says, ‘You can’t sit here.’ And we said, ‘Well, you have stools and you have booths.’ And he said, ‘Yes, I do … but I still can’t serve you, and I will not serve you — and these booths that are here now will not be here tomorrow.’ … He must have worked all night long, because Monday morning [the booths and stools] were gone, and they never returned until they closed that drugstore sometime in the ’80s.”

But ASCORE’s work wasn’t finished once a business was desgregated. “Even after the lunch counters opened up, we had to go and test these places, because oftentimes we were still not served,” Spells recalls. “You ordered something [and] you still didn’t get served, and you had to sit for hours and hours and hours and still not be served.”

In those cases, she explains, “after enough students would go and sit in and we were taking up seats from customers, then eventually they began to serve us.”

Opening doors

After the sit-ins, ASCORE turned its attention to desegregating other public facilities, including Pack Library, the S&W Cafeteria and Aston Park.

“We had two parks,” notes Ferguson. “One for the whites, which was the best-appointed [and where] they had all the facilities … and then Walton Street Park, which was reserved for African-Americans. And there was virtually nothing there other than a swimming pool and some swings.”

Spells, who served on the committee to desegregate Pack Library, remembers meeting with the director. “We told him that we felt the library should be open to all people, because everyone paid the taxes that serviced that library,” she recalls. “The director said that it was fine with him, but he would have to take it to the board of trustees. And they met and approved to open up the library to everybody in the community.”

The next time ASCORE met with the director, says Spells, “He gave us a tour of the building, and one of the first things he showed us — right in his office — was a vault where they kept the historic books. Then he showed us downstairs where they had meeting rooms and programs — we didn’t have anything like that at our little library — and I thought that was really interesting. I later became a librarian, and one of my strengths was doing public programming.”

Encouraged by its success, ASCORE began tackling employment issues. “We went to Bon Marche, Winter’s, Eckerd and a number of other places to see if we could open the door for some jobs that were not just porter jobs or maid jobs but jobs … [such as] cashiers or counter help, doing the kinds of things that most white people could easily get,” says Chambers.

In preparation for these meetings, group members did role-playing exercises. “Someone would play the role of the store manager or store owner, and one of us would play the role of students talking with that store manager or owner,” Ferguson explains. “We’d be given a series of scenarios that we needed to be prepared to respond to.”

But merely getting to talk to the person in charge wasn’t always easy. Chambers remembers when he and a few other ASCORE members went into a store right after it had snowed. “We asked one of the clerks in there if we could see the manager, and he said: ‘Well, he’s not here. He’s up on the roof shoveling snow.’ Well, that sounded kind of strange to us, because if he was up on the roof shoveling snow, why was the porter — who was a black guy at the time — sitting down? Because he didn’t have anything else to do. It didn’t make any sense to us. We just kind of laughed and walked out; we knew what the deal was.”

Despite such challenges, the group ultimately succeeded in opening doors that had been closed to African-Americans. The telephone company hired its first African-American operator, and Sears, Dillard’s and Belk hired their first African-American counter help. In the textile industry, companies such as Mills Manufacturing hired African-Americans to work “on the floor” for the first time.

Passing the torch

As each group of ASCORE students prepared to graduate, they recruited, mentored and trained more rising juniors and seniors to take their places. “Those of us who started this really wanted to go away to [college], and we wanted to make sure that there was a group there to carry it on,” Ferguson recalls.

Etta May Whitner became ASCORE’s second president; she was succeeded by Barbara Turman (who later married Ferguson).

It was during Turman’s tenure that the students decided to target the Winn-Dixie on College Street (across from the Buncombe County Courthouse).

Cheryl Ruth Hunley spent a lot of time walking in the picket line outside the store. “There were no African-American bag boys,” she explains. “That was a job young [white] kids could get but we couldn’t.” (“In hindsight,” she adds with a laugh, “I don’t even think the idea of a girl [having that job] ever crossed our minds, because it was a bag boy.”)

Still, it was a bold choice, because this was the closest grocery store to the black community. “Initially it was really hard, because a lot of the people in the neighborhood didn’t think [the boycott] made much sense … and they crossed the line,” Hunley recalls. “But I can remember Mr. Roland reminding us, ‘Do not say anything, do not respond, just look ahead and keep walking.’

“Eventually, little by little, we noticed that some [customers] would just pass by, and then at some point we realized, ‘Oh, this is really working.’ They stopped crossing the line.”

After several months, says Hunley, “We got a call that we didn’t need to report [to the picket line]. … We had been successful.”

Hunley also remembers helping desegregate a drive-in restaurant. “I can’t remember its name. All I remember is that it had some of the best root beer,” she recalls.

After several visits during which no one would wait on her and her friends, “One night we pulled in and the young lady came to the car — it was a drive-in, with the carhops — and took our orders, and it was just, ‘OK, that was no big deal anymore either.'”

Essential lessons

By the time ASCORE disbanded in 1965, some 100 students had passed through its ranks. Most were from Stephens-Lee, though some came from Allen and Asheville Catholic.

Hunley remembers feeling energized by her involvement with the group. “I felt like I was oriented toward issues at a very early age,” she says. “I felt empowered by that — that we could go about solving our problems in an orderly way by standing up for what we believed in.”

And Chambers says the experience taught him “that in order to effect change, you have to be part of change. It helped me grow [in] inner strength and with the kind of vision that if I believed something, I could achieve it.”

Almost all the ASCORE members went on to college — a remarkable achievement in itself for that time. Chambers (who’s now retired) had a career in engineering, Hunley eventually became a school principal in Atlanta, and Spells worked as a librarian at the New York Public Library and the Free Library of Philadelphia before retiring and moving back to Asheville. Ferguson, meanwhile, became a leading civil-rights attorney (perhaps best known for defending the Wilmington 10 in the 1970s).

Ironically, Ferguson also wound up working on the Asheville school-desegregation case (B. Lee Allen et al. v. Asheville City Board of Education) in 1970 — thus “completing the work that I started doing as a high-school student.”

What strikes him most about the ASCORE experience, he says, “is that it really was an unlikely thing for high-school students to do or be able to do — and as far as I know … there was no other high-school group that got involved in the sit-in movement in the way we did and that had the success we had in bringing about the desegregation of a city.

“It just kind of lets you know that folks and young folks and anybody who are determined to make change can — even when it seems like they can’t.”

Honoring ASCORE

As part of its 10th anniversary celebration, the Center for Diversity Education, an Asheville-based nonprofit, has organized several events commemorating the ASCORE crusaders. Two events — re-enactments of sit-ins at the former Woolworth’s lunch counter and what is now the Fine Arts Theater — have already taken place. Upcoming events include:

• Saturday, Nov. 5: A reception and dance with heavy hors d’oeuvres, band and cash bar will be held at 8 p.m. in the Stephens-Lee Recreation Center, 30 George Washington Carver St. General admission is $25; patron tickets are $100.

• Sunday, Nov. 6: An awards ceremony honoring former ASCORE members will be held at 3 p.m. in UNCA’s Highsmith University Union Alumni Hall. Noted civil-rights attorney James Ferguson, a founding member of ASCORE, will give the keynote address. Following the program, there will be an opening reception for the historical exhibit With All Deliberate Speed in UNCA’s Highsmith Union Gallery. The exhibit, which traces school integration in Buncombe County, will be on view through December. Both events are free and open to the public.

So proud of you, Viola.