In this week’s cover package, Xpress takes a look at a few of the Big Ideas that have shaped the local area throughout its long, colorful history.

A sea change: desegregating the Asheville City Schools

“Less than 50 years ago in our community, our schools were segregated by race, and barriers for children living in poverty prevented many from participating in public education,” notes Kate Pett, executive director of the Asheville City Schools Foundation. “Today, every child in our community goes to school, and it is our expectation that every child will be supported and nurtured in such a way that they can succeed, regardless of their circumstances outside of school, their special needs or even their giftedness.”

“This is a sea change,” she adds.

Desegregation of the city’s school system began on Aug. 24, 1961. “Without any fanfare five black students headed to class at what had been an all-white school,” according to an archived issue of the Asheville Citizen-Times. There were no protesters as the first- and second-graders made their way to Newton Elementary School on Biltmore Avenue, the paper reported.

But that was only the first step toward desegregating the school system in the wake of the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which stated that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Decades of legal action and even violence followed.

Another key step was merging Lee Edwards and South French Broad high schools to create an integrated Asheville High School in 1969.

O.L. Sherrill, the new school’s co-principal at the time, reflected on the change in a historical report from the Center for Diversity Education. “There were lots of fear factors,” he recalled. “The mascots were changed. Team colors, school colors were changed. … They decided they would have co-presidents for student bodies and most other clubs and activities.” Tensions festered, however, and on Sept. 29, a riot broke out, closing the school for a week, according to the report. A citywide curfew remained in place for three days.

Asheville City Schools began implementing a court-ordered desegregation plan in 1970, according to the Citizen-Times. And in 1988, a Civil Rights Act discrimination complaint concerning continued racial imbalance at some city schools led to a second desegregation order, which remains in effect today.

Despite some lingering tensions, however, Pett believes school integration has made a huge contribution to furthering the ideal of equality.

“Today, the Asheville City Schools are some of the most diverse places in our community,” Pett maintains. “Our middle and high schools particularly bridge the barriers of wealth and poverty and allow students to forge meaningful relationships with students from every neighborhood in our community. This is a tremendous success that is worth celebrating and protecting.” — Jake Frankel

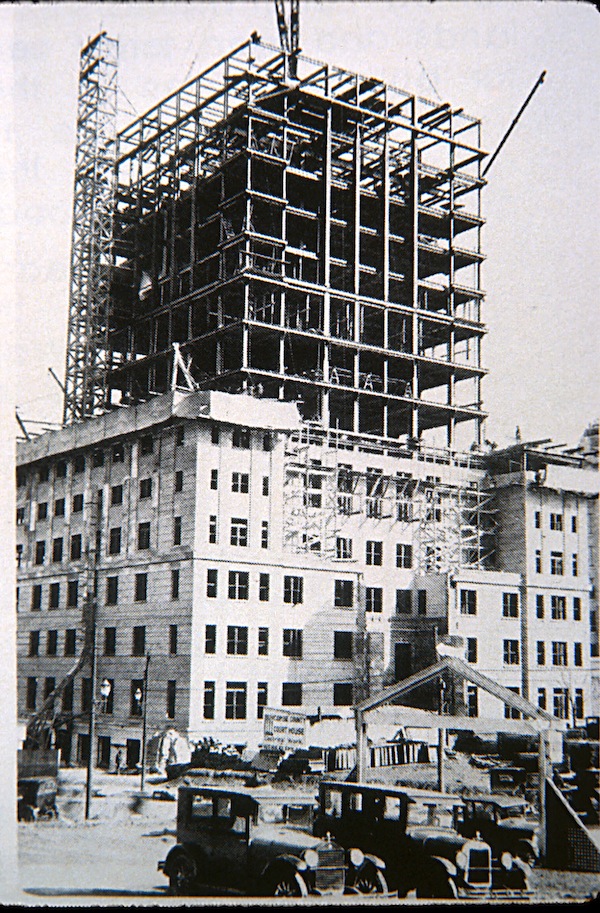

E.W. Grove envisioned his downtown Asheville project, the Grove Arcade, as the center of commercial and civic life in Western North Carolina. The original plans called for a 14-story structure, but the Depression economy halted full completion. Photo by Hayley Benton

Grand scale: The Grove Park Inn and Grove Arcade

One of Asheville’s most important landmarks, the Grove Park Inn celebrated its 100th anniversary this year. The striking granite structure was the brainchild of E.W. Grove, who made his fortune with his anti-malarial Tasteless Chill Tonic. In the 1890s, the patent medicine was said to be more popular than Coca-Cola.

Like many others, Grove was drawn to Asheville from his Tennesee home by its reputation for healing: His doctors said breathing the clean mountain air could help his bronchitis. In 1909, he purchased 408 acres in North Asheville, a portion of which would become the inn property. He also developed the surrounding residential neighborhood and assorted other projects in and around the city.

To realize his grand hotel dream, Grove had 400 men working 10-hour shifts six days a week for a year, according to the hotel’s website. Granite boulders, some weighing as much as 10,000 pounds, were hauled from Sunset Mountain using mules, wagons and ropes. Once the inn opened, fresh water for guests was piped in 17 miles from Mount Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi.

Over the years, the luxurious hostelry’s several owners have added multiple wings, a spa, a golf course and various restaurants. It’s helped put Asheville on the map as an international tourist destination, hosting 10 presidents (most recently Barack Obama) as well as innovators such as Thomas Edison and Henry Ford.

In the early 1920s, Grove began work on another influential Asheville landmark: the Grove Arcade. When the downtown structure opened in 1929, it was the largest building in the region, offering a mix of stores and office space that made it “the center of commercial and civic life in Western North Carolina,” according to the arcade’s website. Even as it was under construction, Grove asserted in 1927: “It is generally conceded that the Arcade building would do justice to a city many times the size of Asheville. It is by far the finest structure in the South and there are few, if any, finer in the country.” However, Grove didn’t live to see the building completed: He died later that year, and the 14-story tower planned to crown the massive complex was never built.

During World War II, the federal government took over the building, summarily evicting 74 shops and 127 offices, according to the website. The arcade later housed the National Climatic Data Center, which moved to the new downtown Federal Building in 1995. The city acquired the historic structure in 1997, and the renovated Grove Arcade reopened in 2002, once again becoming one of the region’s premier commercial buildings. — Jake Frankel

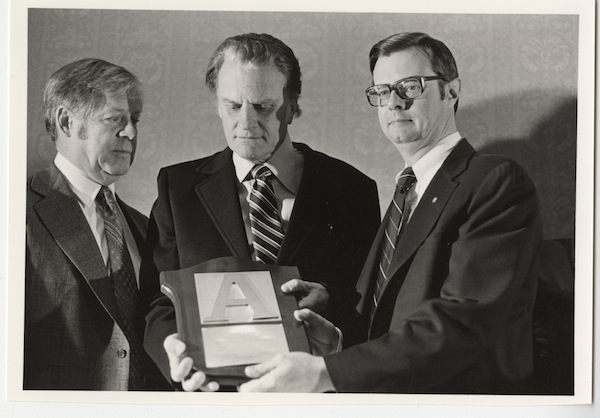

Billy Graham, receiving an “A” in appreciation for his contributions to Asheville and the area, at a 1973 Chamber of Commerce event. N.C. Collection, Pack Memorial Library

‘Reaching the lost’: the Rev. Billy Graham

Among the area’s best-known residents, the Rev. Billy Graham has lived in Montreat since the 1940s, helping put Western North Carolina on the international map. Buncombe County Commissioner Joe Belcher credits the acclaimed televangelist’s work as one of the biggest local success stories of the past century.

“Thanks to Rev. Billy Graham and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, tens of thousands of individuals have been led to Christ,” says Belcher. “Their radio station, 106.9 FM, and training ministry at The Cove have also contributed to the economic development and history of Buncombe County.”

Opened in 1987, The Cove is a 1,200-acre Christian conference center in East Asheville that hosts leading Bible teachers from around the world and thousands of guests each year. The retreat brings to life Graham’s big idea of providing “a place where people could leave the demands of daily life, come to study God’s word and be trained to reach the lost for Christ,” according to its website.

Known as the “pastor to presidents,” Graham has counseled every commander in chief since Harry Truman. A celebration of his 95th birthday at the Grove Park Inn in November was a star-studded affair, with a guest list that included Sarah Palin, Donald Trump, Rupert Murdoch and others. — Jake Frankel

George Vanderbilt’s grand vision for the Biltmore Estate helped define the area for more than a century. Photo by Jake Frankel.

A lasting legacy: Biltmore Estate

Ever since construction began in 1889, Biltmore Estate has had an enormous impact on the Asheville area.

George Vanderbilt, the grandson of railroad and shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, pumped a fortune into realizing his dream of the ultimate country retreat. Along the way, the project cultivated a bustling community of craftsmen and other workers who helped lay the foundation of the local economy for many years to come. The neighboring Biltmore Village was developed as a place to house the thousands of workers needed to build the 250-room French Renaissance chateau, which was completed in 1895. Today, Biltmore Village is an upscale commercial center featuring hotels, restaurants and shops, flanked by the estate proper.

But the legacy of Vanderbilt’s big idea extends far beyond the immediate neighborhood. Supervising architect Richard Sharp Smith went on to design commercial, civic and residential buildings across town, making a major contribution to Asheville’s distinctive charm. Opened in 1893, the Young Men’s Institute (now the YMI Cultural Center) was originally pitched to Vanderbilt as a project to benefit the estate’s black construction workers. Vanderbilt financed the Smith-designed structure, and in 1905 he sold it to an independent group. One of the oldest African-American institutions in the South, the YMI helps anchor the historic black neighborhood known as The Block.

Biltmore Estate’s roughly 125,000 acres stretched all the way to Mount Pisgah, helping preserve much of what’s now Pisgah National Forest. The Biltmore School of Forestry was the first such institution in the U.S., as Vanderbilt hired such pioneering figures as Frederick Law Olmsted, Gifford Pinchot and Carl Schenck to manage his vast holdings. Pinchot later served as the first chief forester of the U.S. Forest Service, helping put into practice nationwide the principles he’d practiced here.

Today the Cradle of Forestry, billed as “the birthplace of forest conservation in America,” commemorates the vision of Vanderbilt and the men he brought in to implement it.

In modern times, Vanderbilt’s descendants have transformed a portion of his extraordinary estate into one of the country’s premier tourism destinations, with a winery, a luxury hotel, restaurants, outdoor activities and more. — Jake Frankel

Worst to best: Buncombe County school construction program

Thirty years ago, conditions at the Buncombe County Schools ranked among the worst in the country, and in 1983 state lawmakers, believing that local officials weren’t meeting their responsibilities, created a 0.5 percent local sales tax earmarked for funding capital improvements for public schools.

Those revenues have been instrumental in funding the construction of 15 new school buildings and renovations at dozens of others. Many local leaders credit that state law and corresponding efforts by the school board with transforming Buncombe County’s school system from one of the worst in the country to one of the best in the region.

“Due to this spending mandate from Raleigh, the condition and quality of the 42 current Buncombe County Schools facilities are now envied throughout the region and the state of North Carolina,” says David Gantt, chair of the Board of Commissioners. — Jake Frankel

A rendering of the current Interstate 26 configuration, dubbed “malfunction junction” for many years. Over the years, vying plans to replace it with a new design have encountered opposition based on cost, scale and how much damage they’ll do to surrounding neighborhoods. Photo courtesy of Asheville Design Center.

I-26 connector: To build or not to build?

Discussed for decades, a proposal by the N.C. Department of Transportation to construct a new stretch of interstate through Asheville has yet to be realized. Over the last year, many local leaders have been pushing to advance the project, but it remains unfunded.

The project would involve major upgrades to existing sections of Interstate 240, as well as several miles of new roadway connecting Interstate 26 south of Asheville and U.S. 19-23 (the future I-26) north of town. The exact routes haven’t even been determined, though neighborhood activists have long worried about detrimental impacts on West Asheville and Montford. Previous proposals supported by the Chamber of Commerce would have have required the demolition of dozens of homes in the predominantly African-American Burton Street neighborhood.

Supporters say the road is needed to address safety concerns and boost the economy. Tentative DOT projections call for construction to begin in 2020, though many hurdles remain before that can happen.

“It’s frustrating. We definitely need that,” says Buncombe County Commissioner David King. “I know there’s resistance for different reasons, but I’m optimistic.” — Jake Frankel

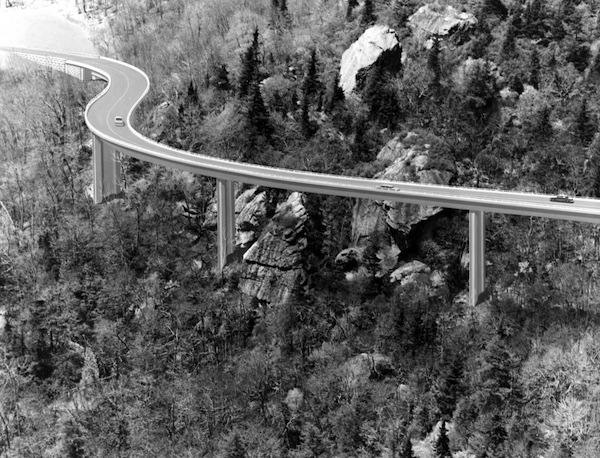

Starting in the mid-1930s as part of the New Deal, the Blue Ridge Parkway would take until 1987 to complete, when work was done on the Linn Cove Viaduct, pictured here. The scenic road is the country’s most visited national park. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

America’s most popular park: the Blue Ridge Parkway

The Blue Ridge Parkway has had a major economic impact on Asheville, bringing millions of travelers to town over the years. It’s also given locals easy access to a wide range of outdoor activities. The 469-mile scenic road offers stunning vistas as well as hiking and biking opportunities. It stretches from Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the south to Shenandoah National Park in the north, passing through the heart of Buncombe County en route.

Construction of the ambitious project, a product of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-era programs to help stimulate the economy and put people back to work, began in 1935. But while federal funding was critical, key supporters such as Sen. Harry Flood Byrd of Virginia, landscape architect Stanley Abbott and countless other politicians, landowners and assorted influential figures were instrumental in making it happen.

“It is the first use of the parkway idea, purely and wholeheartedly for the purposes of tourist recreation distinguished from the purposes of regional travel,” wrote Abbott, quoted in a 2010 Smithsonian magazine article. After an intense yearlong battle, Western North Carolina secured the roadway in lieu of an alternate route proposed by Tennessee.

World War II halted construction, however, and the popular section connecting Asheville to Craggy Gardens wasn’t completed until 1950. The final link, the Linn Cove Viaduct north of Asheville, wasn’t finished until 1987. Another popular section just south of town is also the parkway’s highest point: 6,053 feet near Mount Pisgah.

— Jake Frankel

In 1992, the official North Carolina state LGBT pride march made its way through Asheville, marking a major step in the local community’s struggle towards public equality. Photo courtesy of John Yelton

Going public: the struggle for LGBT equality

Asheville held its first gay pride event in 1988. It wasn’t publicized, there were no marches, and few photos have survived of the gathering behind what’s now Club Hairspray.

“Folks parked their cars so that no one passing by on the street could see or recognize anyone,” John Yelton recalls. “Definitely no press was alerted or allowed: It was a dangerous thing to do. Pride? Times sure have changed.”

Over the next quarter century, however, LGBT Ashevilleans would come out of the shadows, demanding equal rights with an increasingly public presence.

In 1992, a statewide pride march made its way through downtown Asheville. And in May 1994, mere months before Xpress’ first issue hit the stands, 1,300 people crowded the Civic Center for an Asheville City Council meeting. Two weeks earlier, Council member (and future mayor) Leni Sitnick had proposed a resolution protecting city employees from discrimination based on their sexual and gender identity, among other criteria. It had passed on a 4-3 vote. The hourslong debate on a second reading saw many locals condemn the LGBT community. Even Sitnick asserted that the measure “is not a gay rights ordinance,” and provisions explicitly protecting LGBT people were removed from the final draft in favor of more general protections. Even so, the measure was approved by the same narrow margin.

Flash-forward nearly 20 years, and the Council chamber was again the site of lengthy debates over LGBT rights. In 2010, some new Council members pushed for domestic-partner benefits for city employees. Supporters said it was a civil rights issue, while noting the LGBT community’s growing clout.

“The gay community votes with its dollars,” then Council member Esther Manheimer said as she voted in favor of the move. “And they are an economic force to be reckoned with.”

The fight was far from over, however, as the measure drew stringent objections from then Mayor Terry Bellamy in particular. Two years later, a more sweeping resolution supporting LGBT equality saw hundreds of people show up to debate the issue and Asheville’s changing values. Ministers such as the Rev. Wendell Runion asserted that this was “not in line with the values of our community.” Bellamy, meanwhile, blasted her opponents, calling some criticism aimed at her “a lie from the pit of hell.”

But supporters also cited the city’s reputation for tolerance. Yvonne Cook-Riley, a transgender Buncombe County native, said, “Asheville has afforded me the right to walk down the street without being attacked; to be with my friends and dress as weirdly as we want while having fun safely.”

And this time, the vote wasn’t close. Only Bellamy objected to the resolution, and afterward, LGBT supporters toasted “to equality” as they marked a significant victory in a long war. Just months later, Ashevilleans ensured that Buncombe County was one of the few in the state whose voters rejected Amendment One, a statewide same-sex-marriage ban.

Local activists have also kept the pressure on outside the halls of government. In 2010, a series of alleged assaults on LGBT individuals led to the first We’re Not Bashful march.

The following year, Asheville became the headquarters of the Campaign for Southern Equality and the site of the inaugural event in its WE DO civil disobedience campaign, which has since spread across the Southeast seeking to overturn same-sex-marriage bans.

The Rev. Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, the group’s executive director, said Asheville’s history of activism made it an appropriate base for a regional struggle “that usually gets enforced behind closed doors, and the pain usually stays in the privacy of our own lives. But what’s happening right now is that we are making this story public.”

And Ashley Arrington, the community outreach coordinator of Blue Ridge Pride, stresses that while WNC’s more than 80 LGBT groups have made progress, many challenges remain.

“Youth homelessness, adoption laws, fair housing, gender-neutral bathrooms, health care and, yes, even racial equality in the LGBTQ community are still out there to be tackled, and they can and should be on a local level,” she points out.

— David Forbes

Hitting the brakes: the push for a development moratorium

Development has been a common theme in many big ideas aimed at reviving a moribund downtown and propelling its continued evolution. But attempts to block or slow the pace of development in Asheville have also been a significant factor in the city’s political landscape.

Often, that opposition has flared up in response to specific projects, but activists have proposed an outright moratorium several times over the years, and bumper stickers supporting such a move can still be seen around town. The movement peaked in 2007-08, however, when groups such as the Mountain Voices Alliance and Asheville City Council member Robin Cape sought to suspend all development in the city center until new guidelines were in place.

“There is nothing wrong with taking a pause to plan,” activist and former City Council candidate Elaine Lite said at the time. “Do we want to maintain our quality of life? Why is bigger better?”

Emotions ran high, and even progressive activists and politicians who’d often fought side by side in prior political battles now found themselves at loggerheads during the bitter debate. At the March 25, 2008, City Council meeting, some residents, upset about Council members’ failure to support a moratorium, questioned Council’s integrity; Vice Mayor Holly Jones shot back that those assertions were “slander.”

Even some progressive Council members feared that such a move might exacerbate Asheville’s housing shortage and rising cost of living; meanwhile, city legal staff noted that similar moratoriums in other areas had triggered lawsuits. In the end, the proposal failed to win sufficient support; if it had succeeded, downtown Asheville would look very different now.

The battle also presaged a split among local progressives that continues to this day. A 2010 proposal by Council member Gordon Smith and others called for overhauling the city’s development rules to allow greater density without City Council review of projects that included affordable housing. But the idea was fiercely opposed by many of the activists who’d pushed for a moratorium three years before. Lite, for example, said it was an attempt to “bypass the democratic process.” It didn’t happen then, but some on the new Council have already said that changing the rules to allow denser development is a major priority for 2014. Meanwhile, the pro-moratorium forces remain an important part of the city’s politics. — David Forbes

The more traditionally-designed Buncombe Courthouse rises above Pack Square in 1928. Photo from N.C. Collection, Pack Memorial Library.

‘Hinge on hell”: City Hall and the Buncombe County Courthouse

Big ideas are nothing new in Asheville, and few have affected the cityscape as much as the fight over the design of City Hall and the Buncombe County Courthouse. In the 1920s, Asheville was booming, as the once-sleepy mountain town doubled its population in less than two decades. Some civic leaders wanted noted architect Douglas Ellington to redesign the city’s central square, with stylistically similar, linked government buildings, a bus station and a park.

But strong wills, stubborn egos and conflicting ideas of what a civic building should look like derailed the plan. Determined to have an art deco City Hall, fiery Asheville Mayor John Cathey once publicly denounced a Chamber of Commerce panel that got in his way as “a bunch of jackasses.” Edgar M. Lyda, who chaired the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, was equally set on a more traditional structure.

The falling-out produced the two starkly contrasting local government buildings we have today — and soured city/county relations for decades.

For an in-depth account of how this feud shaped Asheville, see: http://avl.mx/03w. — David Forbes

Flattened: the mall that nearly ate downtown

Accustomed to a bustling downtown, it’s hard enough for today’s Ashevilleans to conceive of a central business district consisting mostly of boarded-up buildings. Try imagining a huge swath of downtown wiped out by a mall. But in another case of dueling big ideas, it almost happened.

“Ironically, one of the biggest successes in our community resulted from a giant financial failure,” observes David Gantt, chair of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners. “During the Depression, Asheville refused to join many other cities in the country [in defaulting] and decided to pay off its indebtedness instead. The money used to pay for the huge Depression debt service created an inability to participate in programs like urban renewal in the 1960s, which basically leveled the ‘old buildings’ and constructed shiny ‘new’ downtowns.”

The city had finally paid off its Depression-era debt in 1976. Some, including developer John Lantzius, maintained that the abundance of historic buildings represented a unique opportunity. But in 1980, malls were in their heyday and, desperate for revenue, many politicians and other local notables embraced a proposal to simply demolish much of the city center.

So the Downtown Commercial Complex proposal appeared poised to sweep the field — and much of downtown with it. The city was to spend nearly $40 million buying and demolishing 11 whole blocks of downtown, containing 85 buildings, to make way for a massive mall. Backers included the mayor, the heads of five major banks and many local businesspeople.

But other locals, particularly downtown business owners and tenants led by businessman Wayne Caldwell, came together as Save Downtown Asheville, arguing that the debt and the loss of historic treasures would devastate the city in the long run. Another group, informally known as “the Asheville 1,000,” coordinated their efforts to fight the project — and, in the process, formed important community alliances.

A 1981 bond referendum was overwhelmingly defeated; opponents such as attorney John Powell said it would amount to “a $40 million mortgage on our homes and businesses.”

By the end of the struggle, even mall proponents acknowledged that it might have been for the best. Former Mayor Gene Ochsenreiter told the Asheville Citizen, “At least the town is now aware of the fact that we have a definite problem downtown. Now perhaps City Council will get together with city planners and devise a plan for [its] redevelopment.”

The rest is history. — David Forbes

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.